James Romm - Dying Every Day: Seneca at the Court of Nero

Here you can read online James Romm - Dying Every Day: Seneca at the Court of Nero full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2014, publisher: Knopf, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

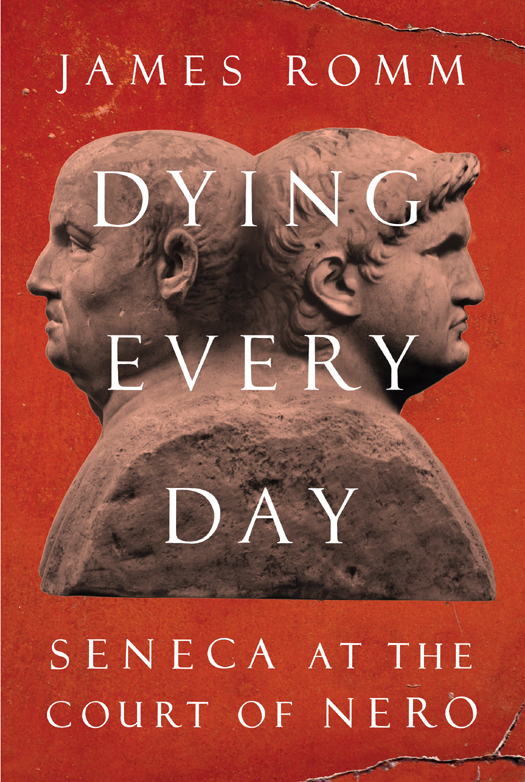

- Book:Dying Every Day: Seneca at the Court of Nero

- Author:

- Publisher:Knopf

- Genre:

- Year:2014

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

Dying Every Day: Seneca at the Court of Nero: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Dying Every Day: Seneca at the Court of Nero" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

At the center, the tumultuous life of Seneca, ancient Romes preeminent writer and philosopher, beginning with banishment in his fifties and subsequent appointment as tutor to twelve-year-old Nero, future emperor of Rome. Controlling them both, Neros mother, Julia Agrippina the Younger, Roman empress, great-granddaughter of the Emperor Augustus, sister of the Emperor Caligula, niece and fourth wife of Emperor Claudius.

James Romm seamlessly weaves together the life and written words, the moral struggles, political intrigue, and bloody vengeance that enmeshed Seneca the Younger in the twisted imperial family and the perverse, paranoid regime of Emperor Nero, despot and madman.

Romm writes that Seneca watched over Nero as teacher, moral guide, and surrogate father, and, at seventeen, when Nero abruptly ascended to become emperor of Rome, Seneca, a man never avid for political power became, with Nero, the ruler of the Roman Empire. We see how Seneca was able to control his young student, how, under Senecas influence, Nero ruled with intelligence and moderation, banned capital punishment, reduced taxes, gave slaves the right to file complaints against their owners, pardoned prisoners arrested for sedition. But with time, as Nero grew vain and disillusioned, Seneca was unable to hold sway over the emperor, and between Neros mother, Agrippinathought to have poisoned her second husband, and her third, who was her uncle (Claudius), and rumored to have entered into an incestuous relationship with her sonand Neros father, described by Suetonius as a murderer and cheat charged with treason, adultery, and incest, how long could the young Nero have been contained?

Dying Every Day is a portrait of Senecas moral struggle in the midst of madness and excess. In his treatises, Seneca preached a rigorous ethical creed, exalting heroes who defied danger to do what was right or embrace a noble death. As Neros adviser, Seneca was presented with a more complex set of choices, as the only man capable of summoning the better aspect of Neros nature, yet, remaining at Neros side and colluding in the evil regime he created.

Dying Every Day is the first book to tell the compelling and nightmarish story of the philosopher-poet who was almost a king, tied to a tyrantas Seneca, the paragon of reason, watched his student spiral into madness and whose descent saw five family murders, the Fire of Rome, and a savage purge that destroyed the supreme minds of the Senates golden age.

James Romm: author's other books

Who wrote Dying Every Day: Seneca at the Court of Nero? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.