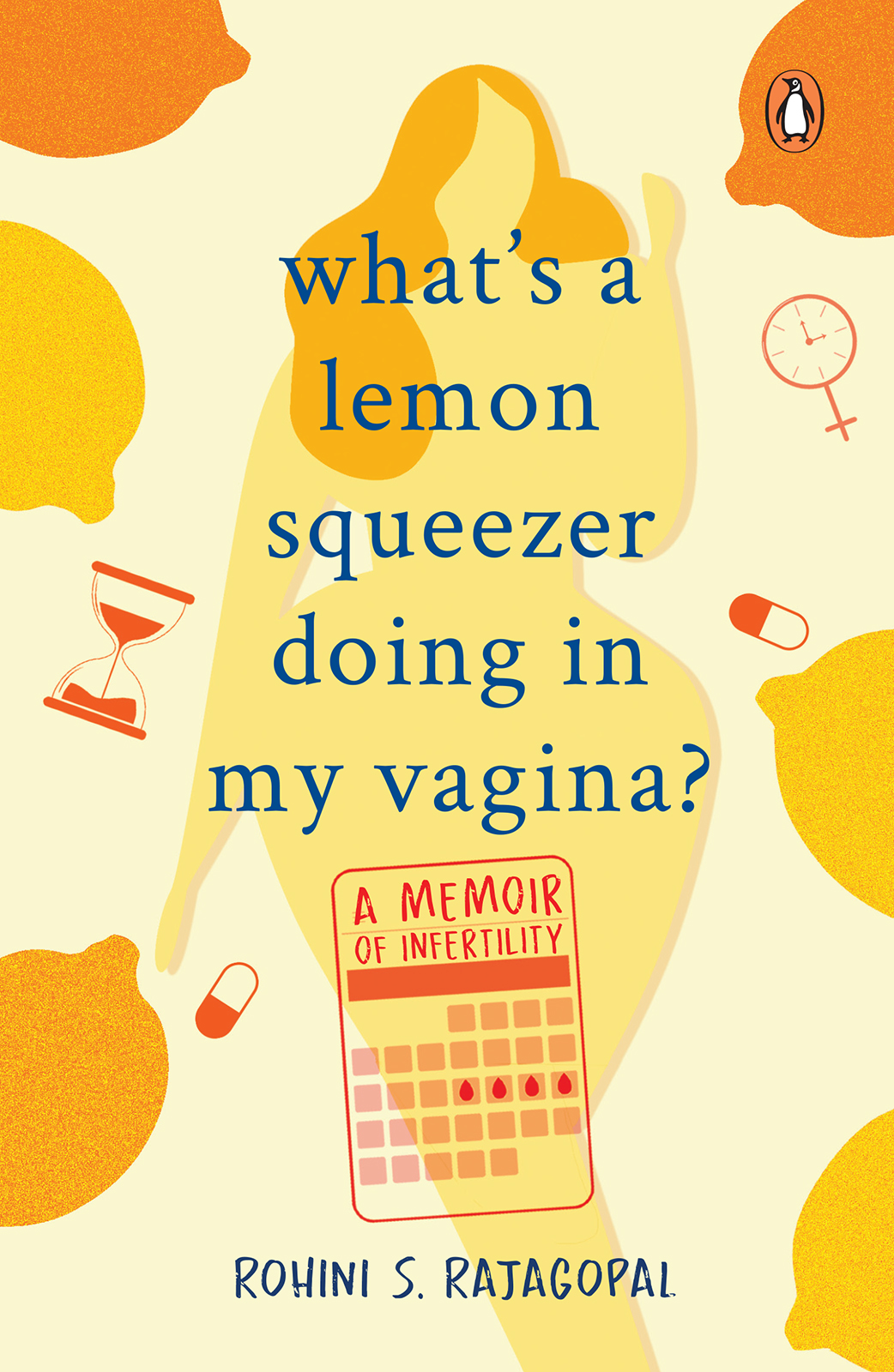

Rohini S. Rajagopal was leading a fairly humdrum life in Bangalore when an encounter with infertility stopped her in her tracks. In a temporary suspension of good sense, she quit her well-paying, flexible-hours job to write this book that narrates her journey from infertility to motherhood. But for her current penury, she has no regrets about that move.

She has a masters degree in English (media and communication). Her special talents include fitting dishes inside overfilled refrigerators and taking three-hour-long afternoon naps without the slightest trace of guilt. You can find her on Instagram at rajagopal.rohini.

Introduction

W hen I completed the first trimester of my pregnancy I went on a calling binge, ringing up close friends and family to share the good news. Most people said, Congratulations! We are happy for you. Or something to that effect. My husband and I had been married for seven years by then, and they must have felt this call was a long time coming. Only one relative asked, Was it IVF? The inordinate delay must have tipped her off.

No, I lied.

Not IVF? You didnt seek any treatment? she sounded perplexed.

No, nothing, I insisted, now cornered by the first lie.

It happened naturally? she persisted.

Yes, I mumbled, wishing this interrogation would just end.

Okay, then. Congratulations! she replied mutedly, still unbelieving. I hurriedly put the phone down and hoped this would never come up again.

That lie was a reflex reaction to a blatant, aggressive line of questioning. In that fight-or-flight moment, my instinct was abject denial. I knew her question came from a place of curiosity, from the need to reconfirm a suspicion. I always knew it. It had to be IVF. My self-preservation instincts kicked in and I signed out of that conversation. But why did I feel apprehended? As if I had been caught in an act of wrongdoing, as if I had to answer for some dishonourable deed? It was the staunch belief in my own shame. The shame I felt towards myself, my body and my reproductive system, which required such a lengthy, convoluted and artificial intervention to have something as seemingly simple and ubiquitous as a baby.

Its been a long and difficult walk from that conversation to this book. From being fully convinced about my own defectiveness and the consequent shame, to shedding such convictions, layer after layer; from disclaiming my history to laying bare the secrets of the hospital folder stashed in the drawers underneath our bed. But I am glad that I started the journey to owning the biggest truth of my life.

This book talks about my five-year battle with infertility. I never thought it would take so long to have a baby or that it would cost us the kind of emotional, physical and financial resources it did. When I found success I promised myself that I would share my story. I felt obligated to those who were breaking the Internet every day looking for a few kilobytes of hope. But once I began writing my story I realized that it is one worth tellinghappy ending or notbecause it throws at least a chink of light on the world of infertility, a world eclipsed by shame, stigma and silence.

While this book documents the series of medical procedures that I underwent, it also speaks about the fear, sorrow, insecurity, desperation, societal pressures and self-expectations that took their toll on my marriage, my psyche and my life. I came to recognize not only how far modern medicine can go but also that it can go only this far. I ended up questioning my own desire to have a child and the notion of infertility itself. I must warn you that though this is a story of inspiration, it is also a story of repeated failures. It is a story about the transformative powers of reproductive science, but it is also a story about the ugliness of infertility treatment. It is a story about birth, but it is also a story about death, multiple deaths.

The second impulse to tell the story came from a more personal and territorial space. My mother-in-law thinks my son is the answer to her dogged prayers, pujas and offerings. My mother always talks about how intense her longing was to be a grandmother and how much the delay in becoming one hurt. She never missed an opportunity to tell guests who came to see my newborn son that he was born after eight long years of marriage, as if the wait was hers. Elderly aunts and uncles in the family use my story like a cautionary tale for newly-weds: Look, they waited so long and see what happened. Have a baby as soon as you can. But none of these accounts talks about me or my suffering. They dont even use words such as infertility. They are versions of my tale told from a sanitized and deodorized distance, situating this story purely in the realm of faith, healing and traditional wisdom. After all, who wants to hear the sordid tales of my vagina, cervical mucus and menstrual blood? This book is an attempt to appropriate my own history, to take back my own narrative. Because this is my story and I am going to tell it. With all the gore and grime.

My third reason for telling this story is that I couldnt sleep for not undoing my own deceit. I waited months, years, but the urge to tell my truth wouldnt die down. It kept bubbling, foaming and frothing inside, making me choke on my own silence. Writing helped release the big woolly knot of unease that was trapped in my chest. Now that I have gathered enough courage to call the knot by its name, give it shape, form and legitimacy of existence, I can finally breathe.

1

How to Get Pregnant 101

E ven though the fertility clinic was only a thirty-minute drive from our house, getting there took almost three months. For both Ranjith and me, it meant admitting that we had failed at something so natural, so fundamental, something that others like us fulfilled daily, unconsciously, with no medical help or knowledge. It meant overcoming our shame, setting aside our egos and revealing our most naked selves to a stranger.

After days of vacillation, Ranjith and I finally stepped inside a clinic run by a well-known infertility specialist. A dear friend had recommended her name to us. We had booked an appointment with the chief doctor herself, fearing that the visit would be futile if we couldnt meet her. She consulted just two days of the week, and if you didnt specifically request a meeting with her you would wind up with one of the numerous junior doctors who assisted her.

The clinic had an unassuming and almost shabby exterior. It was an old, two-storeyed bungalow repurposed into a mini-hospital, the kind where wooden partitions and glass cabins have been arbitrarily placed in erstwhile living rooms, bedrooms and kitchen. The spartan functionality of its office furniture clashed with the arched hallways, ornate window grills and multi-hued mosaic flooring of the house originally built for loftier purposes. A small, shaded yard led to the main entrance. There was no parking and we left our car in one of the by-lanes nearby. I missed the glitz and swankiness of the all-inclusive corporate hospital, but we were here for the doctors expertise and not to see posh interiors.