For Ma, Baba, Mashi, Dia

And I am quite free, well-free from three crooked thingsmortar, pestle and husband with his own crooked thing.

Mutta, Therigatha, 600 BC

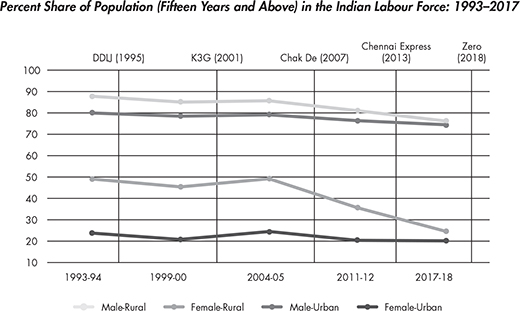

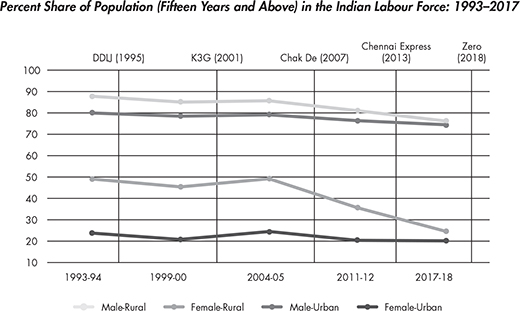

The economic gender gap runs particularly deep in India only one-quarter of women engage actively in the labour market

(i.e. working or looking for work)one of the lowest participation rates in the world.

World Economic Forum 2020

Their fantasies arecan I get married and be happy? Can I own a small car and not worry about petrol prices? Life can be very hard in India, so for two hours, Ill give them real fantasy.

Shah Rukh Khan, 2013

Contents

Preface

Sheltering with Shah Rukh

Koi na koi chahiye, pyar karne wala

(I need someone to love me)

Deewana (1992)

We really dont need more people around us than the ones we feel like

talking to while we are locked up.

Shah Rukh Khan, 2020

M y life has always been heteronormative hell. Ive spent many of my adolescent and adult years pining for the attention of some Great Man or another. I am one of those women your friends talk about. You know, the woman from the infamous refrain, So many great single women but so very few great single men. At work, I am competent and composed. At love, I am a fumbling failure.

Sadly, the market for mates has left me scrambling for cover. Bruised and burned, I oscillate along the spectrum of a banal romantic mania. Some days, the pursuit of sexual romance feels tired and odious. On occasion, monogamy has felt like a fetishized scarce commodity, making a committed relationship the most coveted contract. I lack the poise and insouciance required for romance in Delhi. Im not cosmopolitan or cool enough to grasp the codes of international mating rituals. A spiritual and bodily shame disrupts my love affairs. I experience a consistent discomfort with who I am. My quest for love is doomed. For who can find an iota of love in the world outside if they cant broker some ease within themselves?

In 2019, I entered my mid-thirties with a literary agent, financial independence and no prospect of a partner. Still, I reckoned I would be fine. My life would be a series of monogamous adventures. Yes, I thought, there would be days lost to self-pity and unrequited desire. Perhaps, I would meet someone. But meaningful work and close friends would help forge a truce with the romantic monkeys on my back. In any case, I had become cynical about love. A stable and equal romantic partnership seemed like a fantasy. My love life had become a subordinate part of my identity. I was a working professional, I was a fan, I was a committed friend, I was the primary caregiver for frail parents, I was an upper-caste English-speaking Indian living a life of guilty luxury in a poor country. These experiences defined who I believed I was. Not being someones partner or wife did not sting as much as it did in my late twenties. Smug in my productive solitude, I felt prepared to live in equanimity with my singledom. Then, in the middle of March 2020, India stopped.

In its early days, the development crisis triggered by SARS-CoV-2 kept even half-economists like me frenetically busy. The hours were dizzying, filled with video calls and virtual meetings with government functionaries. I tried to serve the system as best as I could. Blitzed by a barrage of frantic emails and WhatsApp exchanges with transatlantic colleagues, I was hardly ever alone, though I was in lockdown. Deadlines kept me company. As the weeks passed, like many Indians, I struggled to comprehend the apparent global collapsethe once- efficient systems of advanced Western countries were breaking down. In India, militant Residents Welfare Association aunties were using social distancing as an excuse to give free reign to their casteism. On TV, technocrats discussed fiscal space. On the internet, people vented their anger against each other and their governments. Calm doctors preached hygiene and patience, while Covid -deniers and lockdown sceptics screamed conspiracy; hungry workers, tired of pleading for transport back to their villages, took to their feet. As career civil servants offered sincere efforts or cynical excuses, communities came together to cook meals for the elderly. Less hearteningly, millions were losing jobs, employers were withholding wages and those of us with resources were drinking away our pain and fear with liquor delivered to our homes. Little did we know then that the full horror of the pandemic in India had yet to manifest itself. In a year, all our fears, structural injustices and dysfunctions would magnify and meld into an all-encompassing spectre of death and dismay.

I was desperate to have unscheduled spontaneous conversations about it all. To hold someone through this catastrophe. Instead, I was resigned to plan virtual dates with friends, where our intimacy was consistently compromised by patchy internet connections. My best friend, also single, felt as I did. But our mutual love and solidarity, expressed through words and facial cues on a screen, could scarcely calm the panic within. Each night, as I reflected on the day that had passed, I experienced a mix of solitude blended with a lingering sense of loneliness.

Seated on an ergonomically challenged chair, I received the world through screens and windows. I watched women wage war against the viruswives caring for their in-laws, mothers reprimanding children for not washing their hands, an underpaid female army of community health workers, nurses and contact tracers performing essential services. In my own neighbourhood, so reliant on the labour of domestic workers, wives now cooked and cleaned for large families with no help from their husbands. The men would spend hours on loud phone calls with office colleagues and clients, anxious to signal great productivity. They were eager to return to their workplaces, the core of their personhood. Married women retreated into endless hours of domesticity. For some, this was business as usual. We are used to being at home, a colony housewife told me, but the work without my maid is much more. This lockdown is toughest on men and childrenthey go out a lot more than we do. As we exchanged pleasantries across our rooftops, she hung clothes up to dry. Data shows that the majority of Indian women have sacrificed careers and the world beyond their homes, all for their family and children. If anything, the virus made this sacrifice feel more thankless and laborious. Domestic violence inflicted by male partners was rising through the lockdown; women were exhausted with no time to themselves.

Witnessing these online and offline scenes, I felt self-satisfied and blessed. From the vantage point of my veranda, I stared at the toiling mothers, restless husbands and irate children, thanking myself and my exes for sparing me a life of domestic suffocation. I felt grateful that I was doing fewer dishes and had the freedom to participate in the world as a paid professional. On social media and on virtual friend-dates, I would spot the rare equal partnershiphusbands washing dishes, wives conducting webinars. These exceptional relationships felt as unreal to me as the romantic fantasies sold in Hindi films, at least compared to the domestic imbalance on display in my immediate environment. But on occasion, even on my traditional street, within the unfair homes, I could see exhausted wives chatting companionably with their husbands. I envied these couples, although I would never wish to be them. They had conversations without appointments. The rules of traditional Indian marriage mandated them to take each other to the doctor. These couples embodied a kind of easily accessible support I could only fantasize about.

Next page