All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without written permission in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1956 (as amended). Any person or persons who do any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

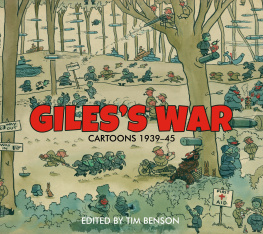

INTRODUCTION

I try to imagine how it must have felt to be a cartoonist during World War II: walking to the office through the bombed streets of your city, diving for cover as the air raid sirens sounded all around you, worrying about friends and loved ones as you listened to daily news from the front.

Life must have been very up and down, with stories of the gains, stories of the losses, and, all the time, lists of the dead, the dying and the missing. You would have found yourself sitting in on the editors conference, the latest headlines in place and only the matter of your cartoon to be resolved. Youd go to your desk to be faced with the usual blank page. What a responsibility. And what pressure there must have been. Your job was to portray the mood of a nation, to put down in drawn lines a nations anger, fear and hope. At the back of your mind, you would know that the cartoon was what people would remember, not the headline, not the thousands of printed words, but the image.

Images define a war. They capture a moment in time and lodge it in the nations memory. Your cartoon would have to resonate with the soldier, the sailor and the candlestick-maker as well as the airman at the front, the factory girl, the farmer and the retired banker on air raid duty.

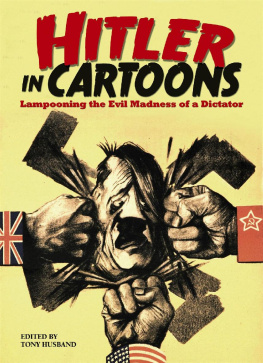

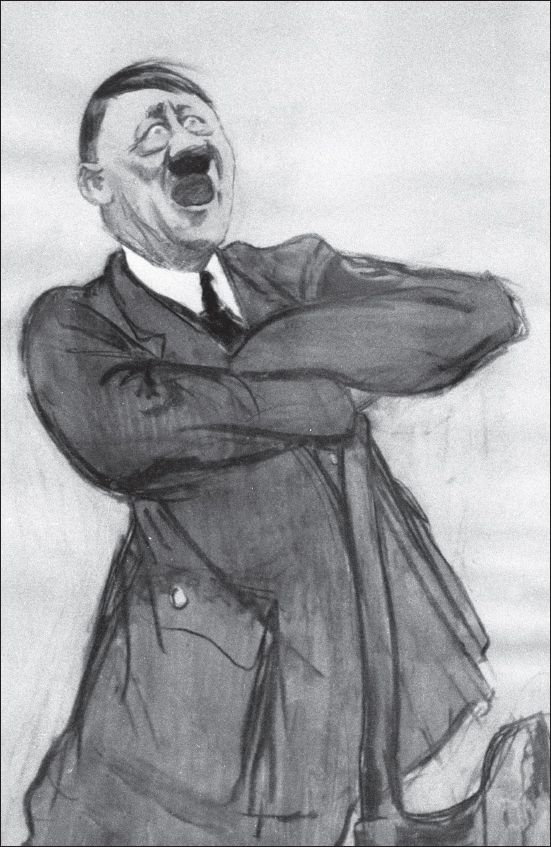

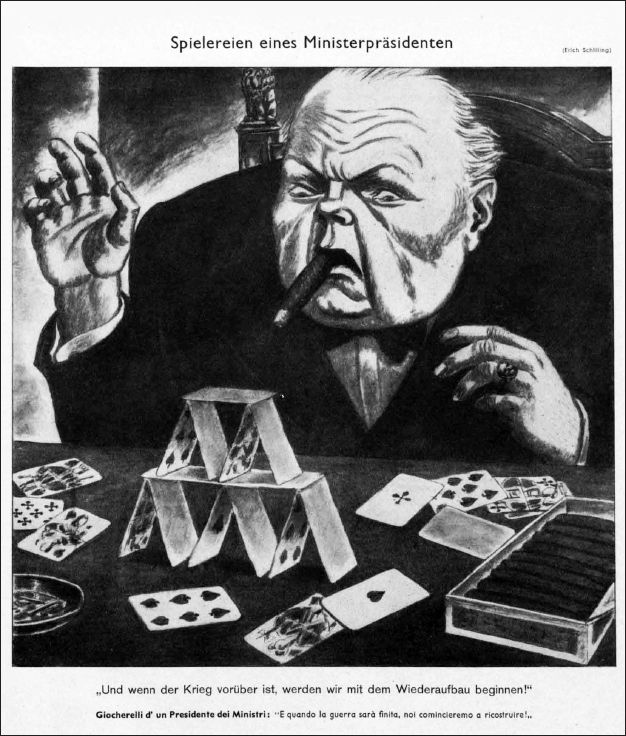

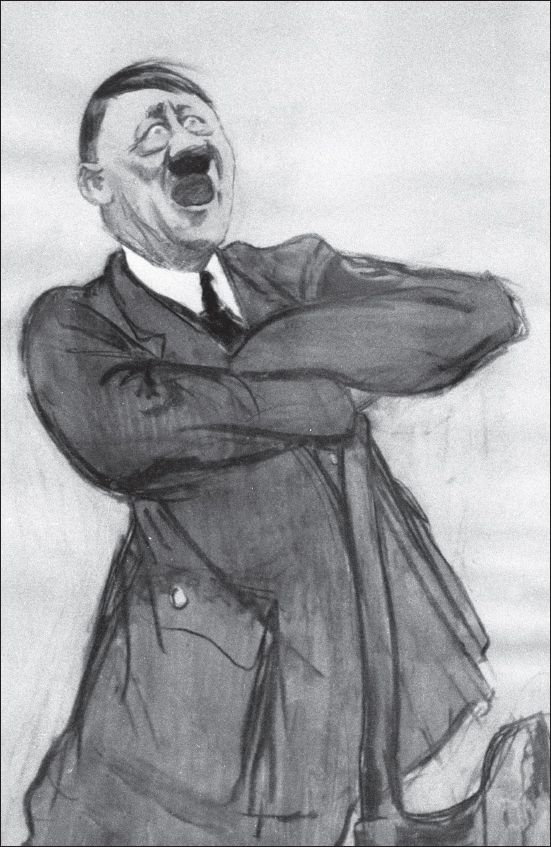

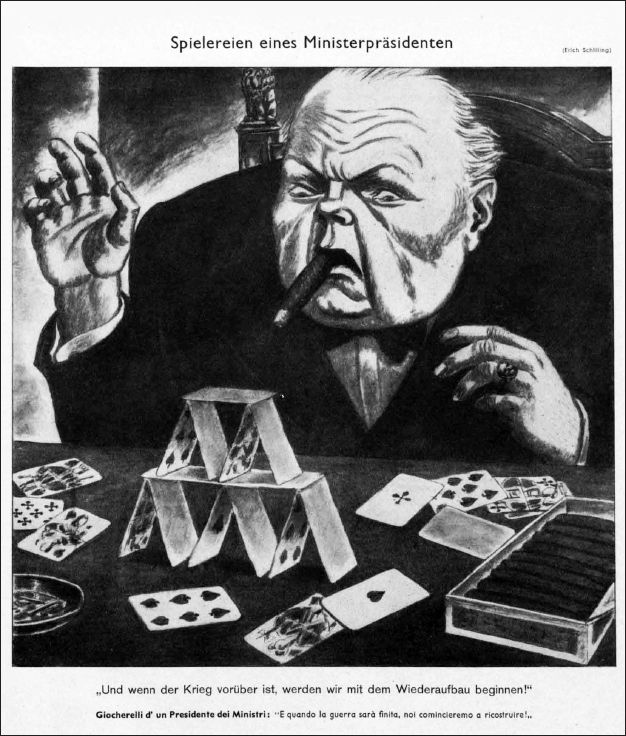

What is so wonderful about the cartoons in this collection is how many cartoonists rose so brilliantly to the challenge. Their pens and minds were sharpened to a fine point by the responsibility put upon them by the gravity of the situation. They produced masterpieces on a daily basis. From every corner of the world, from every side of the conflict, cartoonists of every nation fired their savage, subtle barbs into the heart of the enemy. How Hitler and his henchmen must have raged at the images of them drawn in foreign newspapers. Similarly, Churchill, chomping on his cigar and drinking his nightly whisky, would have sighed at the pompous, drunken fool they made out of him.

Adolf Hitler by Kukryniksy, the collective name for three Russian caricaturists, Porfirii Krylov, Mikhail Kuprilianov and Nikolai Sokolov (see ), 1942

The Baubles of a Prime Minister When the war is over we can start the rebuilding process by Erich Schilling, Josef Goebbels favourite cartoonist, 1941

It must have been really exciting to be a cartoonist then. You were given absolute freedom to vent your rage, to provide a piece of your mind. There were practically no limits. You could characterize your enemy as graphically as you wanted. You could distort and defame anyone on the other side. Indeed it was your duty to do so.

What better way to gain revenge on the perpetrators of crimes than with your pen? I know this from personal experience; I was once beaten up by a gang of skinheads and have spent the last 30 years getting my revenge on them by drawing them as louts and buffoons in magazines and newspapers. To be able to magnify that 100 times during wartime must have been very satisfying indeed

All nations, all sides are represented in this book. It is amazing and fascinating to see how each sides artists handle the war: the British subtle, laidback tea and crumpets with the vicar, discussing progress on all fronts. The Russians, savage, satirical Hitler the demon, as demon he surely was. There was no holding the Russians back from a full frontal assault, the pen scratching venom deeper and deeper into the paper. Cartoonists from the USA showed the ups and downs of GI Joe in a foreign country missing home comforts, while the Germans spat vitriol at anyone who opposed their plan for world domination and made scapegoats of those they had chosen to victimize.

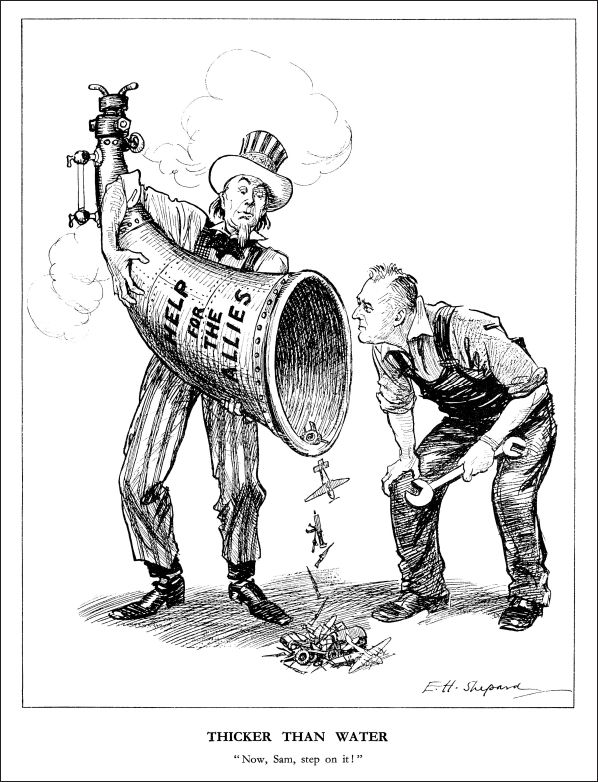

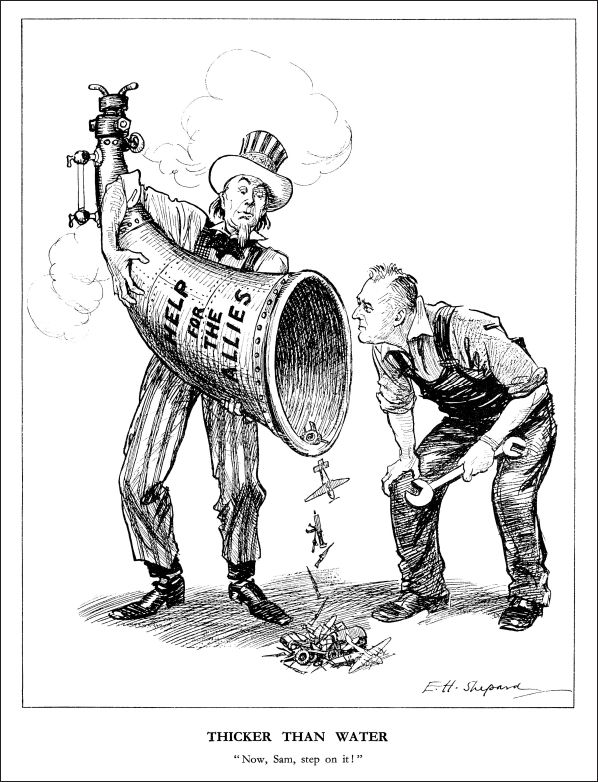

THICKER THAN WATER

Now, Sam, step on it!

Roosevelt as seen by English cartoonist E.H. Shepard in 1940 when France had fallen and the US president had appealed to Congress for Allied supplies

I wonder too who was the crazy Japanese cartoonist who took time before the bombing of Pearl Harbor to draw up a leaflet to drop on the Americans. Crudely duplicated in thousands, the cartoon survived for posterity, a treacherous act by an unknown artist, but did Americans laugh at the words on the picture as we do today?

I am awed at the quality and variety of work here. From mighty historical and beautifully crafted pieces of art to the few lines scribbled quickly on an A4 sheet of paper, they all tell the tale of a moment in history. You can see during the build-up to the war that cartoonists were warning of the grim nature of events to come, the stupidity of failing to learn from history and the shock felt in the aftermath. Simply and surely within these pages, the views from all sides unfold and you can see how very similar they often were, just told in a different way. In those far-off days, cartoonists had great power. They were the stars of their newspapers and had salaries to match their status. They were much sought after and closely guarded by proprietors who dreaded losing them to rivals. Sadly it isnt the same these days, apart from a cherished few. Cartoonists used to be very influential and much feared. As a cartoonist I envy them that. They used that power to great purpose and left us with towering, unforgettable images. If I had a hat, Id take it off to them. Enjoy the work within these pages. It is very special.

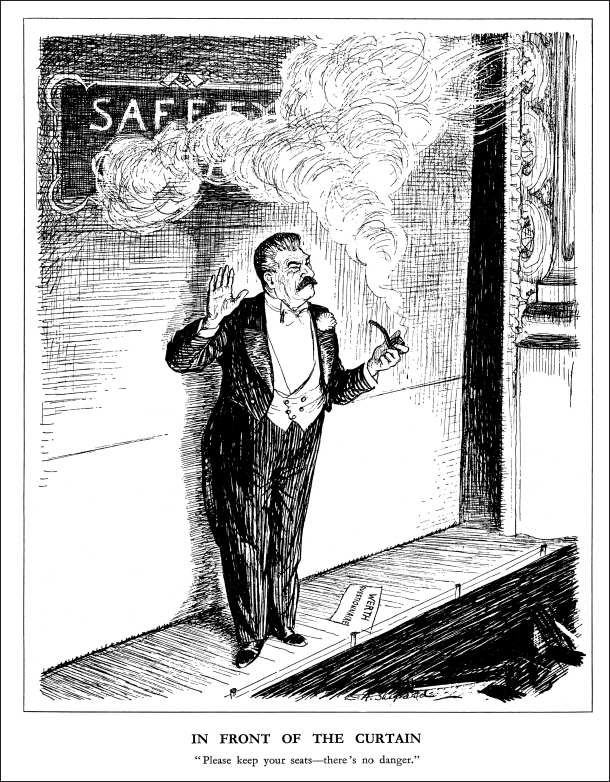

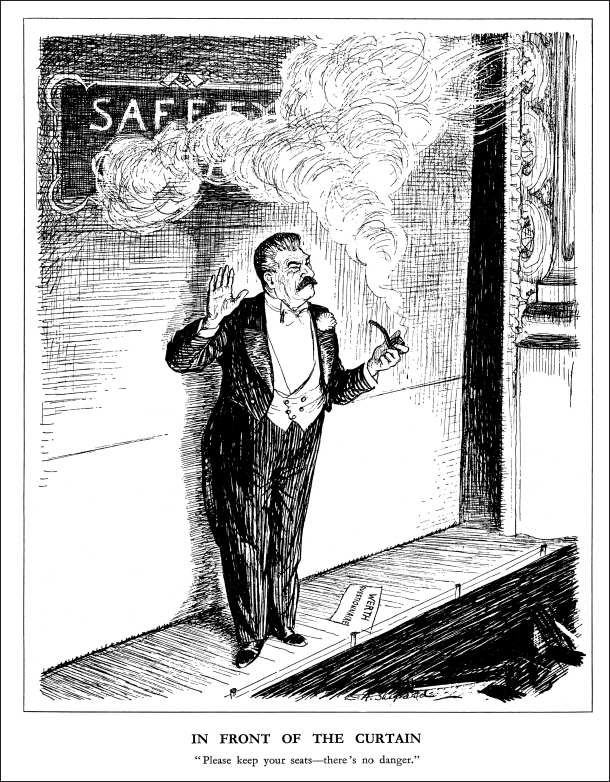

IN FRONT OF THE CURTAIN:

Please keep your seats- theres no danger.

Stalin drawn by E.H. Shepard with more than a whiff of sulphur: the Werth Questionnaire was a series of questions submitted to Stalin in 1946 by Alexander Werth of the Sunday Times. Stalin used his responses to paint a rosy picture of the Soviet Union as a benevolent giant with the friendliest of intentions towards its neighbours

Tony Husband

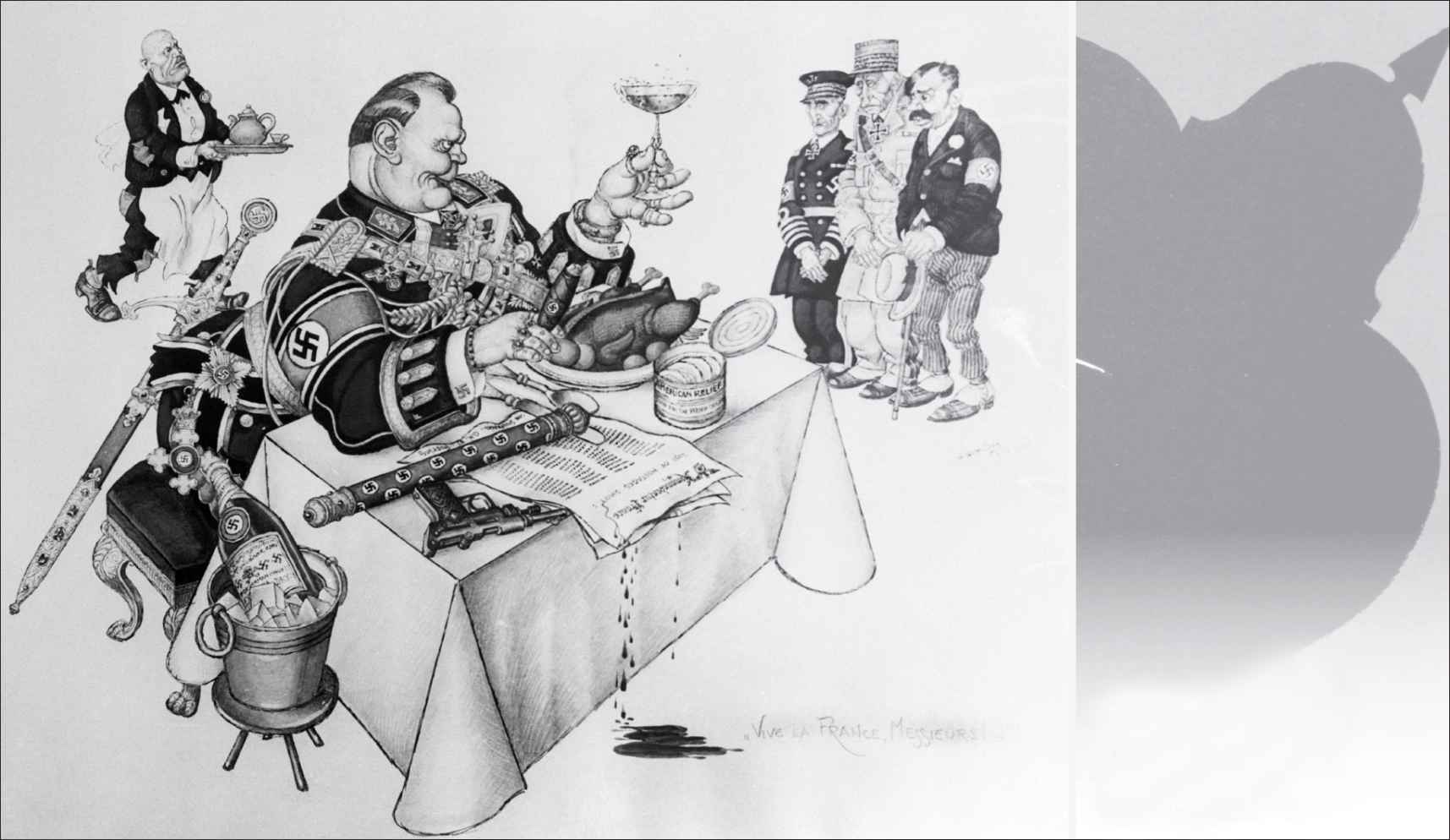

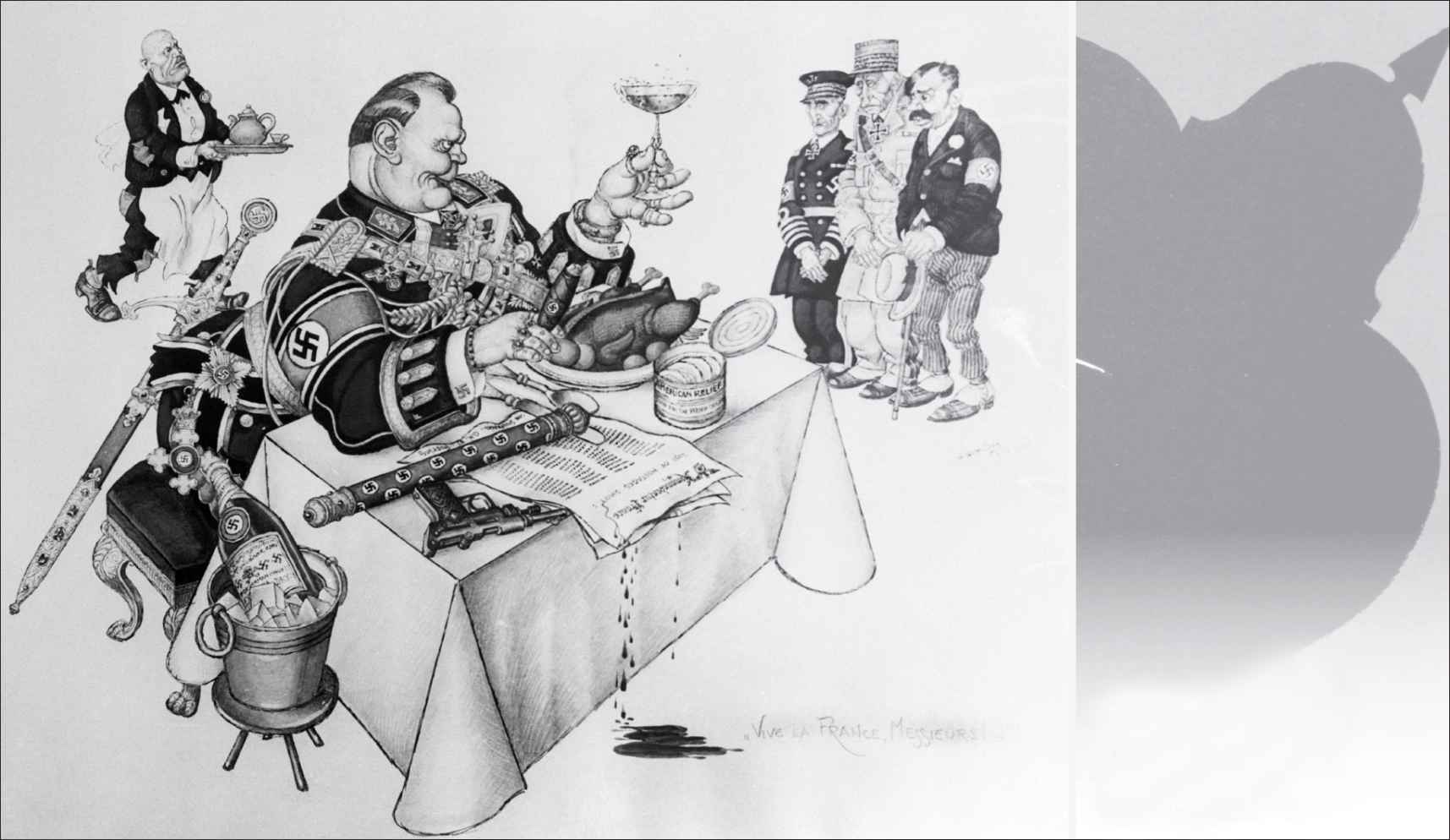

Goerings Banquet: the Reichsmarschall raises his glass to Laval, Petain and Darlan, members of the Vichy government, as a downbeat Mussolini plays the part of waiter, 1943. Artist Artur Szyk shows Goering feasting on US relief rations while blood drips from a list of the names of hostages shot in France