Contents

About the Editor

Dr Tim Benson is Britains leading authority on political cartoons. He runs The Political Cartoon Gallery and Caf which is located near the River Thames in Putney. He is the editor of the annual collection Britains Best Political Cartoons . He has also written numerous books on political cartoonists, including Churchill in Caricature , Low and the Dictators , The Cartoon Century: Modern Britain through the Eyes of Its Cartoonists , Drawing the Curtain: The Cold War in Cartoons and Over the Top: A Cartoon History of Australia at War .

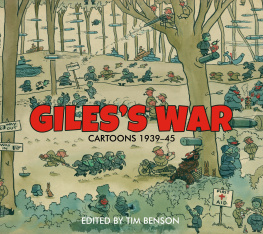

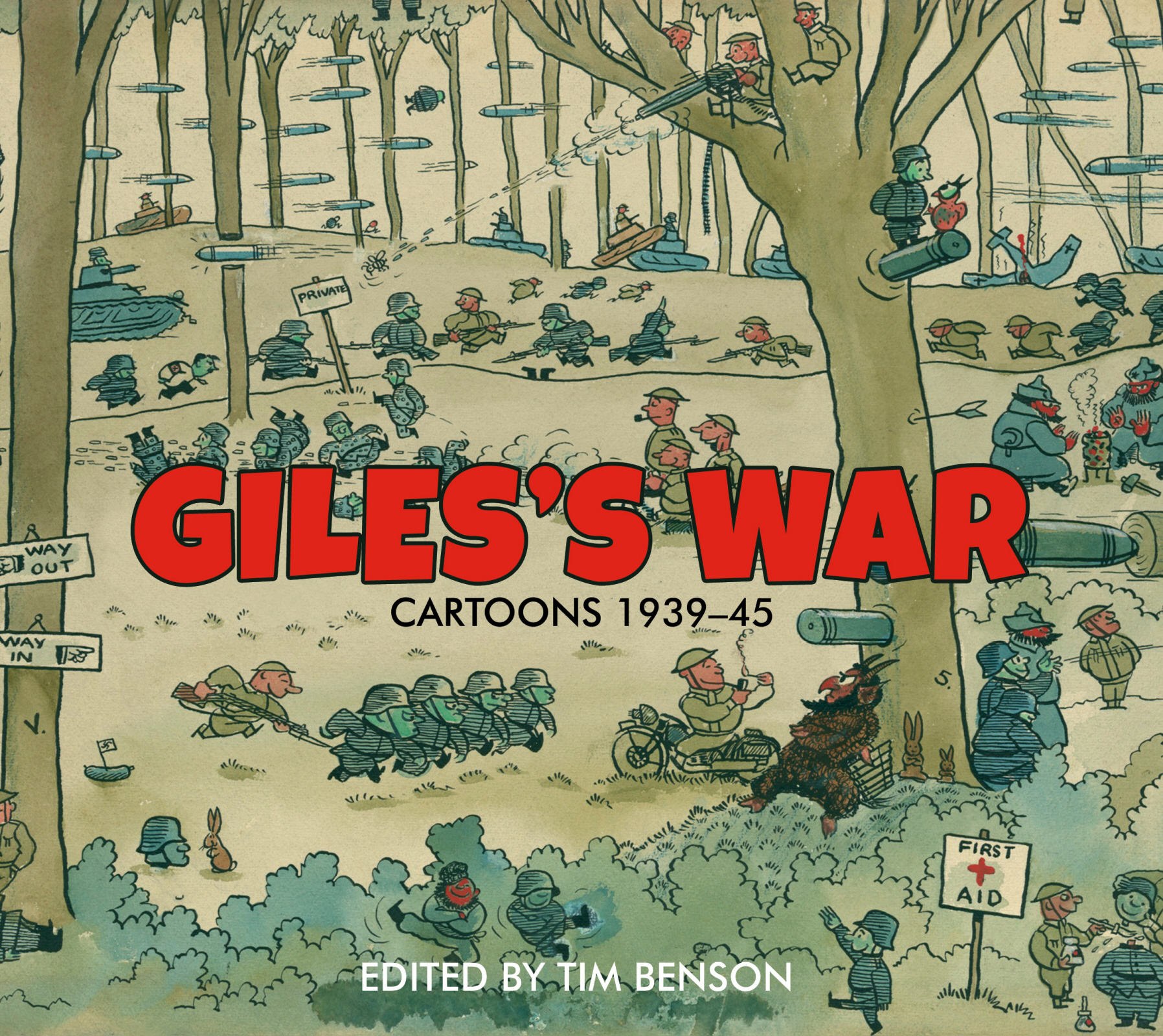

No artist captured Britains indomitable wartime spirit quite like Carl Giles. After the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939, he became known for his charming and irreverent cartoons about life on the Home Front and his remarkable ability to distil the trials of life during wartime into amusing snapshots of Britains stiff upper lip. Starting out in 1937 at a small Sunday newspaper, Reynolds News , his weekly comics became a source of constant comfort for the British public during blackouts, air-raids and rationing. By the time Giles moved to the Express newspaper in 1943, he was well on his way to becoming the countrys best-loved cartoonist.

This collection celebrates Giless work as a young cartoonist forging his reputation during the biggest conflict in global history. During the Blitz, he worked with bombs falling around him one went through the top floor of the Reynolds News building while he was at work there, but luckily did not explode. From 1944 onwards, he saw the final throes of the war first hand, accompanying British forces fighting through Belgium, Holland and then Germany itself, as the official War Cartoonist for the Express . He even witnessed the liberation of Bergen-Belsen concentration camp and Germanys surrender to Field Marshall Montgomery at Lneburg Heath in 1945. Along the way, Giless cartoons helped raise a chuckle for Britons at home and fighting overseas. Spike Milligan, who served in the Royal Artillery, recalled that During the war, Giless cartoons played no little part in boosting my morale. As Lt. Col. Sean Fielding put it in a letter to the Daily Express in February 1945, Giles, in my opinion (and the soldiers) is the only artist who truly caught the stink, the discomfort and beastliness of the front line.

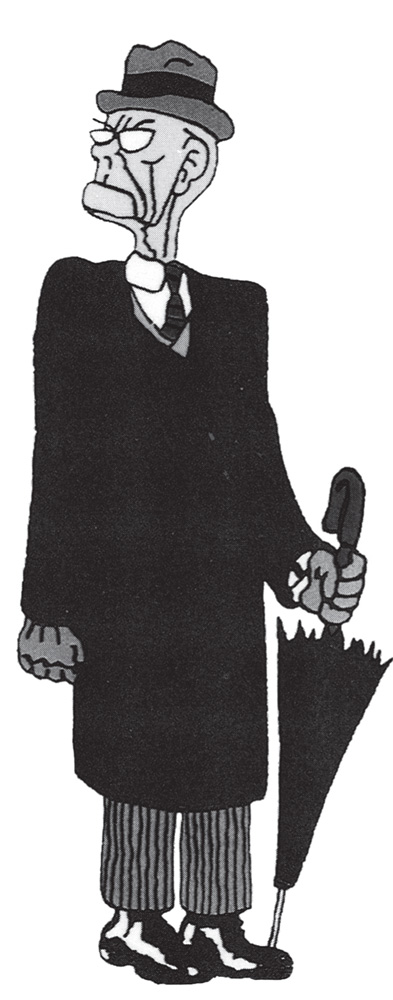

An early Giles cartoon attacking businessmen who profited from the war effort.

Aspects of Giless wartime career remain obscure, mostly because he disliked his official biographer, Peter Tory. According to Rick Brookes, who later replaced him as cartoonist on the Daily Express , Giles was wary of all journalists and avoided interviews and television appearances wherever possible. With Tory, the animosity was mutual: he said that writing Giless biography was the worst and most boring assignment he had ever been given. At Giless funeral, as mourners took their seats, Tory remarked: People fish in a very small gene pool in Norwich. Have you noticed how they all look like Carl Giles? Tory wrote that getting Giles to talk about his private life was like pushing a ton weight up a steep hill this lack of cooperation led to factual inaccuracies and incorrectly annotated illustrations in Torys biographies of Giles.

Giless War brings together Giless wartime cartoons for the first time. It collects over 150 of his earliest drawings for Reynolds News , most of which have not seen the light of day since the 1940s. It shows how humour helped keep Britons spirits up during the darkest moments at home and on the battlefield. And above all, it celebrates the development of a young cartoonist working on an obscure Sunday newspaper into one of Britains most famous artistic talents showing how Carl Giless charming depictions of a nation at war made him a household name by 1945.

* * *

Giles was born on 29 September 1916, above his fathers tobacco shop on City Road in Islington, London well within the sound of Bow Bells, he later remembered. The second of three children, he came from a line of Norwich farmers on his mothers side, and Newmarket jockeys on his fathers: his grandfather had even raced for the Prince of Wales, later Edward VII, in the 1880s. Although he was christened Ronald, Giles intensely disliked his first name and dropped it at the first opportunity. Later, when his fellow animators nicknamed him Karlo because his hairstyle resembled that of the horror film actor Boris Karloff he soon adopted the shortened version: Carl. The name stuck.

The family tobacco shop was next door to The Angel pub. According to Giles, this was handy for his father, Albert: the old man had to pop me somewhere when he went out, he said in 1944. The boozy spirit of early-twentieth-century London was a recurrent theme in Giless work. In 1945, the left-wing journalist and Labour MP Tom Driberg wrote that the infant Giles literally drank up the earthy, sawdusty, beery atmosphere which [would later] save his art from any trace of unreal aestheticism. Although Giles remembered City Road being a bloody awful dump, he fondly recalled the noise of an eight-line tram junction outside and the lovely smell of the street: You got a shower of rain on the dusty streets, and the smells came up like an orchestra, the trams and the oil on the rails and the electricity transformers. The nostalgic atmosphere of Giless cartoons owed a great deal to his memories of London. Decades later, he reminisced about his childhood: Stew on Monday. Washday. The coal piled up in the outside passage (and watch out if you touched it!). A house full of uncles, cousins, nephews and nieces. Grandfather sitting with his pile of toast by the fire.

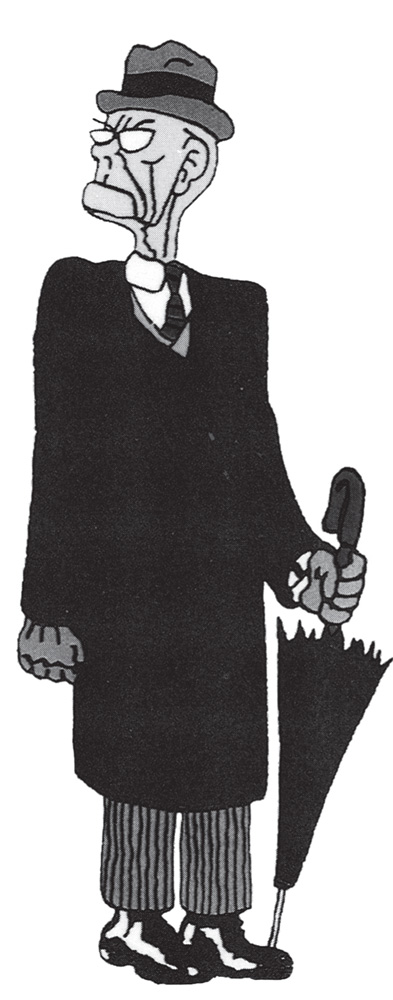

Giles went to his local school, Barnsbury Park. He later drew it as a place for unruly inner-city urchins. His nemesis was a teacher by the name of William James Chalk, who, as Mr Chalky, would became one of his most enduring cartoon creations. He was a sarcastic bugger, Giles recalled. In his class you werent allowed to make a sound. Even if you were dying to go to the toilet you couldnt ask. Ooh, he was a cruel man. I vowed to get my own back, and I did. Chalk left Giles with a permanent dislike of authority in any form, and he spent his entire career ridiculing petty officialdom, be it tax collectors, army officers, traffic wardens, shop stewards and, on the odd occasion, politicians.

Mr Chalky

He claimed that he was never given a chance in art classes at school. He said his fate was to sit under desiccated art masters who made [him] draw that bloody cone, or that wretched green vase which all schools have on the windowsill with never anything in it. He left school at 14 with no formal qualifications.

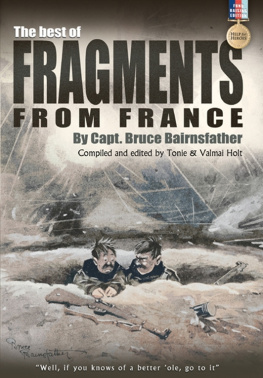

Nonetheless, from an early age he loved to draw. When he was four years old he adored the work of Bruce Bairnsfather, who depicted the British Tommies experiences in the trenches during the First World War. Giles would copy Bairnsfathers cartoons directly from the Bystander , which his father regularly brought home. Giles may have inherited his passion for drawing from his father, who had been an amateur artist. According to Giless sister Eileen, their father loved to paint: His subject was always horses, which he did well but he always fell down when he tried to bring people into his pictures. He got hours and hours of pleasure from painting his horses but never did anything professionally.