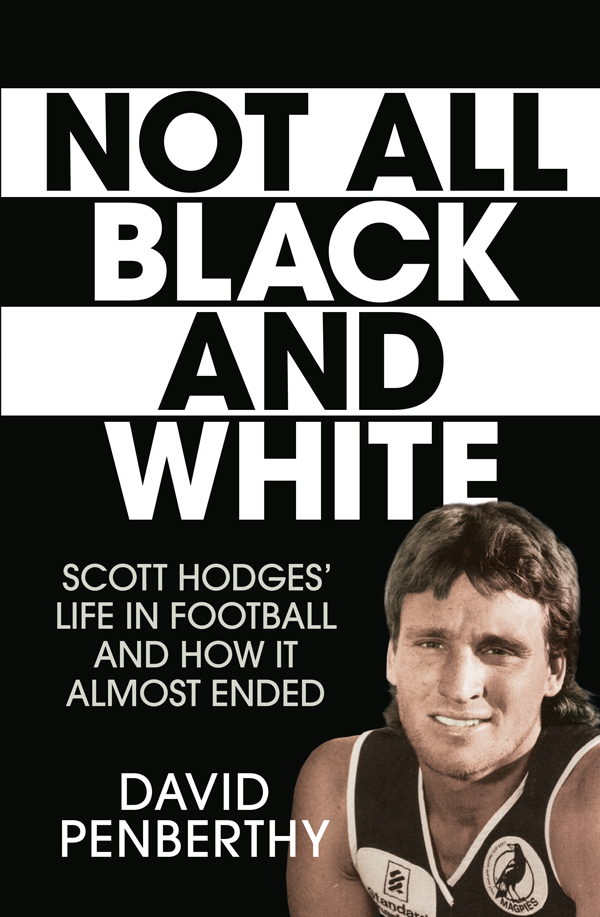

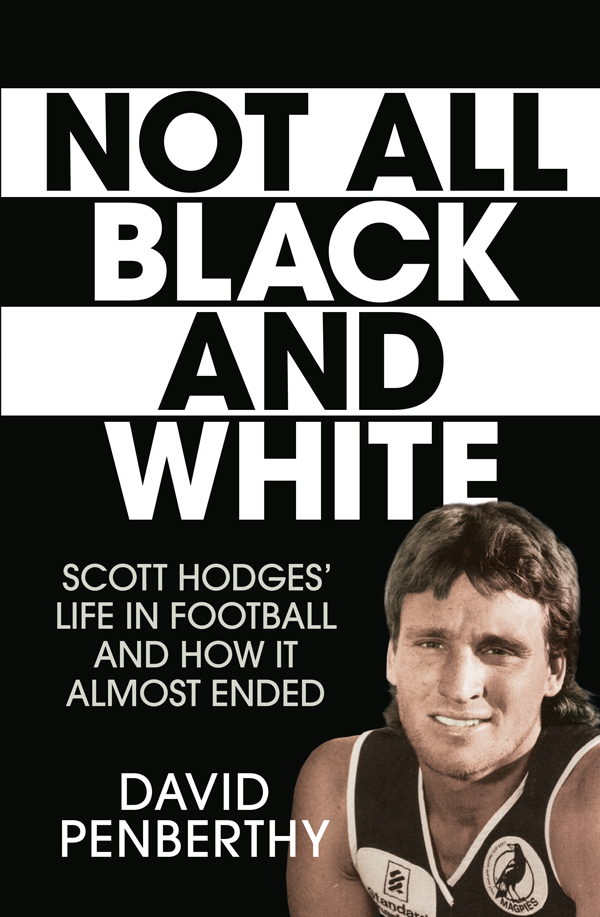

About the Book

On paper Scotty Hodges had it all.

In a football career almost without peer, Scott was drafted as a teenager to represent the team he loved, Port Adelaide, and would go on to win a staggering eight premierships.

He would break the States all-time goal-kicking record, win its highest honour, the Magarey Medal, and be headhunted as the star forward in the inaugural Adelaide Crows AFL team. He had a beautiful wife, herself the daughter of football royalty, and two gorgeous young kids.

Behind all this his life was falling apart.

For years, Scott grappled with undiagnosed mental illness, sending him into a spiral of confusion and isolation, drug and alcohol abuse, anger and violence. He kept this secret from the world, and even began planning his own demise.

This is the gritty and raw account of how an ordinary man overcame extraordinary demons, and emerged the other side with a message of hope and survival.

To my wife Kerry and children Billy, Charlee and Kayne

Contents

Authors note

This is not a book about football.

It has plenty of football in it.

It celebrates the life and career of one of the greatest South Australian footballers ever to play the game.

But it also explains how that life was almost destroyed by an illness that affects so many and which, for so long, has been suffered in silence and isolation.

Scott Hodges has told his story for two reasons.

To remember the good times he enjoyed through his achievements on the football field, and to document the bad times with brutal honesty, so that others in Scotts position can seek the help he avoided for so long.

David Penberthy

August 2017

Of all the heroics that Scott Hodges performed on the footy field, there is one recurring image in my mind that of him limping injured from the ground in the second quarter of the 1990 Grand Final of the South Australian National Football League (SANFL) at Football Park. On the Glenelg bench we breathed a sigh of relief. He was the SANFLs dominant forward. He had won the Magarey Medal, had kicked three goals for the match already and was closing in on Rick Davies goal-kicking record of 151. But he was finished for the match or so we thought.

Impossibly, against the odds, he came back out after half-time. Nothing was impossible for Port on that day. Almost the entire state of South Australia was against them, but they prevailed in what was surely the clubs greatest Grand Final victory. Hodges kicked another three goals after half-time, including his fifth in the last quarter, which broke Davies record. It broke our Glenelg hearts as well.

South Australian football changed forever on that day. In less than a month, the Adelaide Football Club had entered the AFL and Scott Hodges became one of my players.

It was never a happy union. Scott was a Port Adelaide boy through and through and I wasnt Jack Cahill, Ports legendary coach who had a unique talent of extracting the maximum from even the most sensitive or complicated football souls.

Scotty was misunderstood from his very first contact with the club. Neil Kerley (Kerls), that icon of South Australian football, had been appointed football manager of the Crows and was charged with the task of contracting the 52 players who been listed by the fledgling club. With Kerls there was no such thing as negotiation. He presented Scott with his contract, a modest one considering his stellar year, and expected him to sign it like most of the other players had. When Scott sought advice from his mates at Port Adelaide, who recommended he appoint an agent to represent him, negotiations stalled. It didnt help that the agent was a Victorian lawyer which further inflamed Kerls passionate South Australian loyalties. Eventually, the new Crows chief executive, Bill Sanders, took over the negotiations, but the damage had been done. Scott was seen as a reluctant Crow and, because he was genuinely shy and introverted, some of his new teammates mistook his attitude for aloofness and arrogance.

In those early days of the new team, when so many players from ten different clubs came together, team building required sacrifices and special efforts. Because Scott lived so close to Football Park, he didnt often hang around after training to shower and socialise. He just grabbed his gear and left and never really experienced or indulged in the locker-room humour or banter. On one of our pre-season training camps at Rapid Bay, when the squad had been divided into six different teams, and each team allocated one of the old BHP cottages to sleep in, Scott, shy and not well with a respiratory virus, chose to sleep in his car. Rightly or wrongly, he was seen as being indifferent to team spirit and was occasionally called out on it by some of the more vocal or blunt team members. That bred further resentment and impacted negatively on his confidence and relationships within the team. As that first season of the Crows progressed, the Adelaide supporters who were still split along old SANFL club loyalties never really embraced him. Despite his almost total lack of arrogance or conceit, he endured ridicule and abuse from those supporters who still saw him wearing black and white, instead of red, blue and gold.

Still, he played some superb games. He kicked 11 against Geelong, bags of eight against Richmond and Brisbane, another seven against Brisbane and six against the Swans at the SCG. However, as the team struggled interstate on those suburban Victorian grounds and his opportunities dried up, he could never find consistency. The emergence of Tony Modra as the prominent forward restricted Scotts opportunities and, although the two forwards got on well, I felt, as coach, that playing them alongside each other never really worked.

I wish I had known Scott better in those early days of the Crows. Where I saw reluctance and indifference, I should have seen shyness. When I saw resentment, I should have seen his lack of confidence. When I hectored him to push through the pain barrier, I should have recognised that he was genuinely injured. When I saw bullying from other more outspoken, confident teammates, I should have intervened.

Eventually the frustrations of a lack of opportunity, injury and the criticisms from within and without the club took their toll and he quit the Crows and went back to the Port Adelaide Magpies, a haven where he was appreciated and revered. We never saw the best of him at the Crows. In the same way the AFL destroyed South Australian football as we knew and loved it in 1990, so too did it ruin Scott Hodges football story. He grew up a football-loving kid who followed Port Adelaide fanatically, and fulfilled his childhood dream of playing for the Magpies. He achieved great things in that black-and-white guernsey and was loved by the clubs passionate fans. That his time in the AFL did not go to plan should not diminish his legacy. He should be a role model for any working-class kid and a lesson to aspiring coaches that being shy or different does not mean being rebellious.

This long overdue book gives powerful insight into the journey and ordeals of Scott Hodges, a true South Australian football hero. His innermost fears and anxieties are compellingly exposed for the world to see. The Port Adelaide faithful will, of course, love it, but this is a story that goes far beyond football, to people who never knew Scott, to see and to learn from. I wish I knew him that well in 1991.