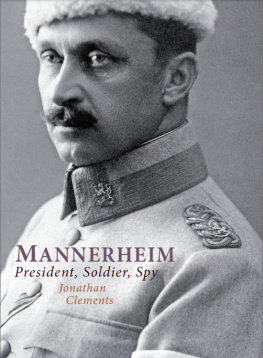

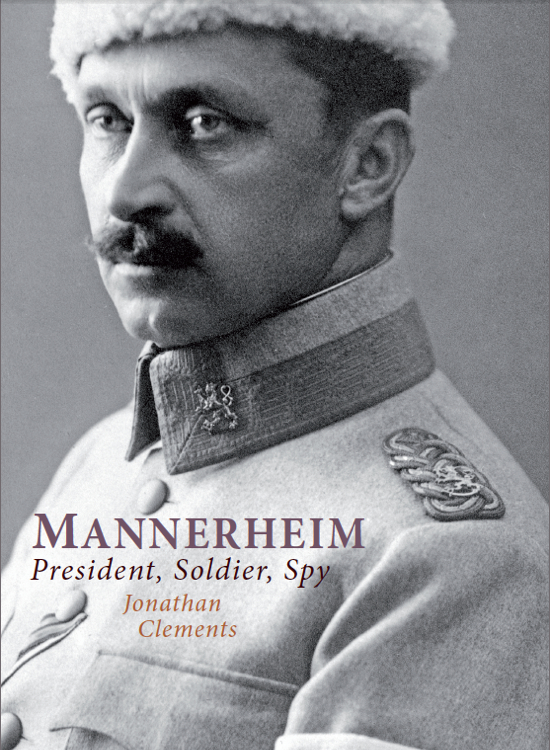

MANNERHEIM

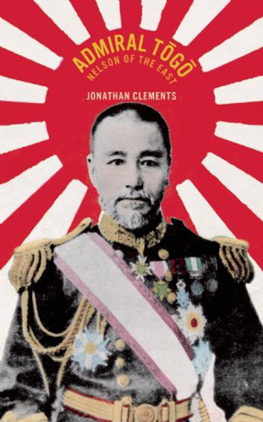

ALSO BY JONATHAN CLEMENTS

AND AVAILABLE FROM HAUS PUBLISHING

IN THE MAKERS OF THE MODERN WORLD SERIES

Wellington Koo: China

Prince Saionji: Japan

First published in Great Britain in 2009 by

Haus Publishing Ltd

70 Cadogan Place

London SW1X 9AH

www.hauspublishing.com

Copyright Muramasa Industries, 2009, 2012

The moral right of the author has been asserted

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ebook ISBN: 978-1-908323-18-7

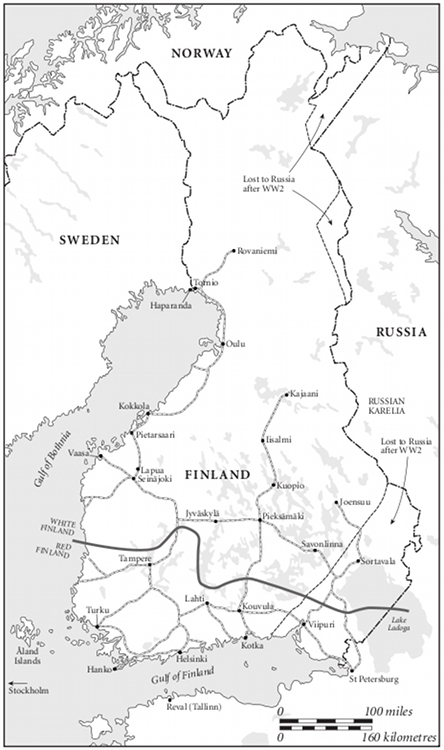

Maps by Martin Lubikowski, ML Design, London

All rights reserved.

Contents

In memory of

Vesa Mki-Kuutti

19532007

Note on Dates

Tsarist Russia used the Julian calendar, which was 12 days behind the Gregorian calendar and in use in much of Europe during the 19th century. From 1 January 1901, the Julian calendar was 13 days behind the Gregorian. This can cause a few historical anomalies modern Russians, for example, are obliged to mark the anniversary of the February Revolution on 8 March, and the October Revolution on 7 November. Mannerheim habitually used the Julian calendar until 1906, when he adopted the Gregorian calendar in his correspondence from China as part of his Swedish cover. In some instances, particularly when dating correspondence between Sweden and Finland, I have given both Gregorian and Julian dates to avoid confusion. All dates after 1917 are Gregorian.

Introduction

Cold Mountain

It was Friday 26 June 1908, a summer day, but the high slopes of the sacred Mount Wutai were still chilly. The Buddhist monks gave thanks even as they shivered was this not further proof of Mount Wutais great holiness? Was it not said that the spirit of the Buddhist deity Manjusri resided at a cold clear mountain? Why not this mountain, even if it were in China?

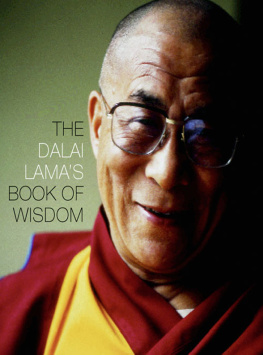

Mount Wutai was not only a sacred site; it was also a refuge for the Thirteenth Incarnation of the Precious Victor, Wish-Fulfilling Jewel, Holder of the White Lotus, His Holiness the Dalai Lama. Forced to flee his Tibetan homeland after a British invasion in 1903, the Dalai Lama now enjoyed an uneasy residence in China, under the watchful eyes of soldiers of the Chinese Emperor of Glorious Succession.

The Chinese Emperor had invited him to come to Beijing to discuss his situation, but for now he was suffered to stay at Mount Wutai. Chinese guards stood watch over the approaches to the mountain, and supposedly kept out troublemakers. Politically, the Dalai Lama was caught between the Chinese and the British, and hoped for a rescue by a third party.

Once every three days, he would venture out from his residence in the foothills, in order to wave at visiting worshippers Chinese and Tibetans, Mongols and tribesmen from eastern Siberia. As was customary, each would present him with a ceremonial silk scarf, or hatak. He would give them one in return.

The Dalai Lamas residence was truly antique. Parts of the temple complex were more than a thousand years old, and it showed. Some buildings were in an awful state of disrepair, and strewn with junk and dirt. Others were incongruously well appointed, dotted with silver gilt idols and paintings of Buddhist saints. Horses quartered on the temple grounds added to the filth, and the stench of manure was overpowering. Regardless, the Dalai Lama donned a ceremonial robe of yellowish-gold and headed out into the daylight. He still had his entourage of monks, some of whom scurried before him as he descended the steps.

The monks remonstrated with the waiting crowd, pushing them back, urging them to make way for the spiritual leader, shouting in Tibetan, Mongol and Chinese. Suddenly, the Dalai Lama saw an unexpected figure. Standing among the worshippers was a towering European figure, a gaunt, moustached man staring right at him. The Dalai Lama paused for a moment in shock and surprise, before continuing his march to the next temple.

Who was the man? Not a British Yellow Head, but clearly one of the men of the distant regions beyond the ocean: a White Devil. The man had been spotted some time before in the distant central Chinese city of Xian, where he had been photographing the retinue of one of the Dalai Lamas lieutenants. He was, it was said, a Swedish explorer called Gustaf Mannerheim.

But there was more to this man than met the eye. The next day, the Dalai Lama sent a monk to summon Mannerheim into his presence. He waited in his chambers, but Mannerheim did not show up. Impatiently, the Dalai Lama sent a second monk, who was astounded to discover that Mannerheim had been changing his clothes and shaving before the audience strangely gentlemanly behaviour. Eventually, Mannerheim arrived, blissfully unaware that he had kept a living god waiting, and unphased by the climb up the steep steps; he was accompanied by Joseph Zhao, his teenage Chinese interpreter.

Mannerheim bowed deeply before the Dalai Lama, who answered with the barest nod, still staring intently at the new arrival. The explorer took a blue silk hatak in both hands and offered it reverently to His Holiness. The Dalai Lama responded by offering him a similar scarf, of white silk.

Mannerheim spoke respectfully, in Russian. His interpreter converted the Russian into Mandarin Chinese, while one of the Dalai Lamas attendants, staring resolutely at the floor, hissed a re-translation into Tibetan.

There was some confusion as to where Mannerheim was from. Yes, Swedish was his native tongue, but he was actually born in a country called Finland. The Dalai Lama was disappointed. He had hoped that Mannerheim was a Russian. The Russian Tsar, Nicholas II, was believed by some Tibetans to be the White Tara, an incarnation of the Bodhisattva of Compassion, and the harbinger of peace in Asia. One of the Dalai Lamas advisers had even told him that the Russian Tsar was contemplating converting to Buddhism if he did so, of course, the political situation in the Far East was sure to change forever.

Quite unexpectedly, Mannerheim admitted that he had met the Tsar. Finland was an autonomous Grand Duchy, but the Grand Duke of Finland was the self-same Nicholas II.

Twice, the Dalai Lama ordered that his attendants check behind the curtains in the hall to make sure that nobody was listening he was afraid both of Tibetan intrigues and his Chinese guardians. The Dalai Lama was very bad at hiding his excitement. His aloof, regal demeanour suddenly collapsed, and he began to twitch nervously. He asked if Mannerheim had a message for him from the Tsar.

Mannerheim was forced to admit that he did not, but offered to carry a message back to the Tsar on the Dalai Lamas behalf. The Dalai Lama hesitated, and asked Mannerheim his rank. Mannerheim revealed that he was a baron, which seemed to please His Holiness. The Dalai Lama presented Mannerheim with a silk hatak for the Tsar, and entreated the visitor to stay another day, so that the Tibetan ruler might ask for something. Mannerheim told him that the sympathies of the Russian people were on his side, when he felt obliged to leave his own country... These sympathies had not been weakened by the lapse of time, and wherever he might be, he could feel sure that Russians, both high and low, watched his footsteps with interest.