DYNASTIC RULE

MIKHAIL PIOTROVSKY

& THE HERMITAGE

Geraldine Norman

CONTENTS

- Title Page

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: The Story Of The Hermitage

- Chapter 2: Boris Borisovich Piotrovsky

- Chapter 3: The Birth of a Dynasty

- Chapter 4: Birth, Yerevan, St Petersburg

- Chapter 5: School & University

- Chapter 6: Travels of a Young Arabist

- Chapter 7: The Arabist at Work

- Chapter 8: Private Life

- Chapter 9: Perestroika

- Chapter 10: Focus on Recovery

- Chapter 11: Turning the Corner

- Chapter 12: Challenges & Victories

- Chapter 13: More than a Museum Director

- Epilogue

- Acknowledgements

- Picture Credits

- Bibliography

- Index

- Copyright

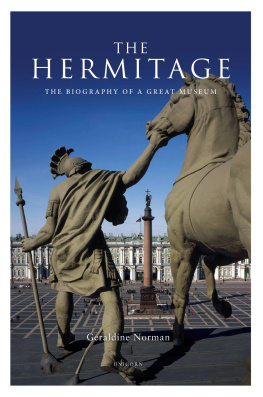

View from the Victory Chariot on the roof of the General Staff Building, looking towards the Winter Palace

INTRODUCTION

It was February 1993 and I was an art market journalist on a London newspaper, intent on getting to know the post-Soviet art scene in Russia. I had determined that my big piece from St Petersburg was going to answer the question: What has happened to the Hermitage since the Revolution?

Peter Batkin, Sothebys fixer in Russia, had promised to introduce me to Mikhail Piotrovsky, the new director of the Hermitage. That was the start of it. Peter, a small, stocky figure who sported stylish black-and-white brogues (of the sort once dubbed co-respondent1) had previously worked as Sothebys chief clerk. He had a gift for finding unlikely solutions, and his Russian assistant, Irina, was similarly talented it was necessary in the Soviet Union.

We caught the overnight train from Moscow and Peter closed the compartment door and secured it with his belt against robbers. Irina had negotiated a mini-van to pick us up at the station which contained two bunk-beds and numerous photographs of naked girls. It was in this vehicle that we went to pick up Mikhail Piotrovsky and his wife to take them out to dinner. Peter disappeared to collect them and was gone a long time. He explained later that there had been a murder in the flat below the Piotrovskys and Mikhail was concerned that his wife should not glimpse anything as they went out past his neighbours door.

There followed a very enjoyable dinner in a casino the only place, Peter averred, where you could get a decent meal. I talked to Mikhail and found him easy to get on with and obviously highly intelligent.

Mikhail arranged for me to go round the museum with a party from UNESCO headed by Ted Pillsbury, director of the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth. To my eyes, the vast building seemed a Rococo masterpiece; it was only later that I learned it was Russian Baroque. And the art room after room after room of it was mostly great and very moving. On the way round I found and bought a booklet of stories recounted by Mikhails father to a journalist about the noble and extraordinary history of the Hermitage, and it sowed the seed of an idea in my mind. What about writing a book?

The Hermitage from the Winter Palace to the Theatre

A party from Londons Royal Academy was also visiting the ending of the Soviet Union had unlocked the marvels of the Hermitage, and everyone was avid to come to see and help. We sat around the table in Mikhails office, and the group from the Royal Academy in London explained how a museum can form an organisation of supporters and how they are able to help the Friends of the Royal Academy is a famously successful organisation; and you want to attract some very rich Friends who will become your sponsors, they explained, there must be some rich Russians. But all the rich Russians are crooks, expostulated Mikhail. I included his comment in my article, which I duly sent to him for checking. He rang me in London to say that the article was fine but there was one quotation hed be happier to do without: Im sure I said it. But it could ruin me, he said. I agreed to drop it.

I believe that was a turning point in our relationship. I could, perhaps, be trusted. After the article was printed I wrote to him and asked whether he would support me if I were to write a history of his museum. For a year I got no answer. Then we met by chance at the opening press conference of the Maastricht Art and Antiques Fair in Holland. Hullo Geraldine, he said. I never answered your letter. Ill just open this Fair, then well find a corner to discuss your idea. We did just that and he agreed to help me.

Maybe he had asked some of his museum colleagues about my reputation and had been told not to touch me with a bargepole. I had been writing a series of articles about fakes in the Getty Museum and elsewhere which had not pleased those in authority. He must have wondered how to respond to my letter and decided that the easiest way was not to answer it at all. When he met me again, he made a snap decision. It was madness to let a dangerous Western journalist loose in a Soviet museum. Well, it may have been post-Soviet by then but only just. It was a sign of intuitive trust for which I am very grateful.

For me, it was the start of a life-changing adventure. I wrote The Hermitage: The Biography of a Great Museum covering the period from Catherine the Great to about 1990, and it was published in 1997. I was then employed by Lord Rothschild to start up the Hermitage Rooms at Somerset House an exhibition space that ran for seven years from 2000. I started the Hermitage Magazine and the UK Friends of the Hermitage in 2003. And now I have written this book to explain to myself and hopefully to others the extent of Mikhail Piotrovskys achievements for the Hermitage.

You might surmise from this account that Mikhail and I are friends. But you would be wrong. Mikhail doesnt do friends he hasnt time for it. He doesnt invite them to visit his flat in St Petersburg or the wonderful dacha in Komarovo, on the Gulf of Finland, that his wife has built for him. He attends and hosts many, many receptions and dinners in his working life; his private life remains a carefully guarded retreat.

All the same, he is convivial, humorous, good company. What else he is, this book will explore a born leader, a natural innovator, a clever manipulator, firmly rooted in his family and more widely in his devotion to Russia. Read on

The arch of the General Staff Building

CHAPTER 1

THE STORY OF THE HERMITAGE

The State Hermitage Museum is the most magnificent gift of the former Soviet Union to posterity both to Russia itself and to the rest of the world. The imperial collections and the Winter Palace of the Tsars now home to the museum were taken over by the Soviet state after the revolution in 1917. Subsequently, nationalisation of great family collections added further masterpieces to the museum.

Some revolutions destroy everything that has gone before, while others deliberately preserve the artefacts of the previous regime so as to demonstrate its wickedly luxurious nature. Happily, Russia adopted the second strategy, so, for example, the magnificent 19th-century Kazan Cathedral in St Petersburg, inspired by St Peters in Rome, became (with a few additions) the Museum of Atheism. Religion was out, but there was no destruction of historic buildings or liturgical treasures. On the night of 7th November 1917 when the Winter Palace was stormed by the Bolsheviks, Lenin himself sent a posse of guards to protect the wing housing the Hermitage museum, and both the building and the collection remained.

Next page