FOREWORD BY THE DIRECTOR OF THE HERMITAGE, PROFESSOR MIKHAIL PIOTROVSKY

T his book was the beginning of Geraldines love affair with the Hermitage. She studied its internal workings, looking for the unusual and the mysterious; she found what she was looking for, fell in love with the museum and began to serve it, in the same way as its faithful staff, the Ermitageniki. Together with Lord Rothschild, she created the Hermitage Rooms in Somerset House, whose seven years of existence have written a beautiful page into the history of the museums life in London and RussianBritish cultural relations. Geraldine went on to found the British Friends of the Hermitage (now called the Hermitage Foundation UK) and for many years has been its executive director. She founded the magazine Hermitage and was initially its editor, financial manager and marketing manager rolled into one. Geraldine initiated a series of exhibitions on British contemporary art in the framework of the Hermitage 20/21 project. With her help, several important cultural projects have been implemented, including the financing of the restoration of the General Staff Building and great films about the Hermitage. Geraldine is an informal ambassador for our museum in the UK and a pro-bono advisor to the director of the Hermitage. All of this developed out of an understanding and sympathy for the spirit of the museum that she acquired while writing this book twenty years ago. Now this new and updated edition is being published and will cast its spell again.

For all her love of the Hermitage, Geraldine has not lost her personal approach to the material she is treating often critical and not always comfortable for the people about whom she about writes. At the very beginning of our acquaintance, one famous British art critic told me: Be careful. This woman is very dangerous! Geraldine, indeed, was already a famous journalist, writing about the unscrupulous vagaries of the art market and often causing trouble for major museums, collectors and dealers. However, I did not have the opportunity to follow his advice. I had already allowed her to study the life of the Hermitage without any restrictions and write what she wanted in her own style. I took a risk (as we often did in the 1990s) and the risk paid off. The book was an important addition to the numerous volumes that had already been written about the Hermitage; it was interesting and unusual, as well as insightful. Geraldine questioned and listened. Many forgotten or underrated characters started talking through her lips; she did not hesitate to question established opinions and reputations. She was above all fascinated by the history of the Hermitage in the twentieth century, and especially by what she saw first hand in the 1990s.

The book is something of a rarity in its treatment of this period. Geraldines account of the decade is spiced with intrigue, which today has been almost forgotten but which seemed very important at the time. Different voices express their alternative views in the book and the memory of them has only been preserved here. At the same time, Geraldine remained objective, which was completely lacking in most of the memoirs that had appeared covering the same period. She was able to convey the dramatic nature of the situation when the social challenges of the Perestroika movement threatened to ruin both the traditions of the museum and the museum itself.

The book is, of course, typically English in its approach. No Russian would have written in this way about the Hermitage. With all Geraldines love for the museum and the accuracy achieved by looking in from the outside, the book has a typically English sense of superiority towards people of a different culture, a feeling that they do not quite match up to generally accepted standards. This feature of a foreigners view also makes the book interesting and useful. Sometimes it is easy to be annoyed by this, but it is these sections of the text that stimulate reflection and response. Some of my writings about the Hermitage and my directors decisions were direct answers to Geraldines book.

This new edition of the Biography of a Great Museum is a guide to the deep workings of the Hermitage spirit. It is fascinating for an insider to read and re-read. I am sure it will be equally so for our visitors.

Mikhail Piotrovsky

Director of the State Hermitage

BY GERALDINE NORMAN

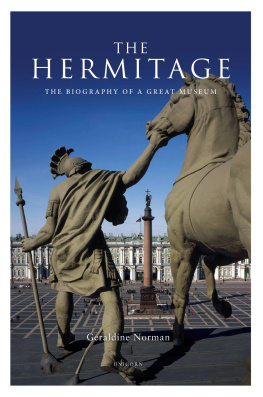

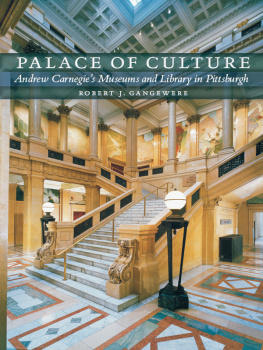

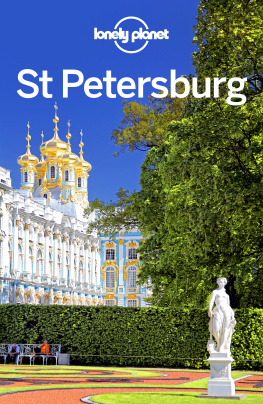

T he State Hermitage in St Petersburg is Russias premier museum. It has one of the greatest collections in the world, on a par with the Louvre, the British Museum or the Metropolitan Museum in New York. Prior to the opening of the extended Grand Louvre in the 1990s the Hermitage was the worlds largest museum. With the completion of the restoration of the General Staff Building in 2014 the Hermitage regained its pre-eminence.

The museum began life as the private collection of the Russian tsars, housed in two pavilions built onto their Winter Palace in central St Petersburg by Catherine the Great, which are known today as the Small Hermitage and the Old Hermitage. Catherines grandson, Nicholas I, had the idea of building a museum extension on to the palace and sharing his own art treasures with the public. This building is known as the New Hermitage and first opened its doors in 1852.

After the Revolution in 1917 the whole of the palace complex was gradually turned over to the nationalised museum, thereafter known as the State Hermitage. It was swollen by accretions from confiscated private collections but depleted by the requirement to share its treasures with Moscow and other regional museums. In the 1930s some great paintings were sold abroad to bolster the national treasury.

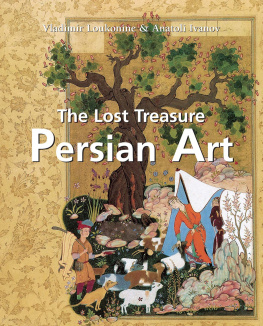

The imperial collection, as it existed before the Revolution, comprised Old Master paintings, Classical antiquities, coins and medals, an Arsenal and some medieval and Renaissance works of art. In the 1920s an Oriental Department was added, in the 1930s an Archaeological Department and in the 1940s a department devoted to Russian works of art.

The collection today is encyclopaedic. In addition to superb works of art, it contains many imperial eccentricities, such as Peter the Greats underwear and Catherines coronation coach. The architectural complex in which it is housed, lining a bank of the River Neva, is one of the wonders of the world.

This book attempts to sketch the museums turbulent history, laying special emphasis on the twentieth century and the interaction of the museum with Russias seventy-year experiment with Communism.

H ermitage is pronounced with a French accent in Russia. It loses its H and the stress falls on the last syllable. It should be spelt Ermitazh, if one follows the standard rules for converting Russian Cyrillic script into our own. It is one of the many French words that entered the Russian language during the reign of Peter the Great (16821725), the crude, seven-foot genius who built St Petersburg and forced his people to shift their mental orientation from East to West.

Both Peter and Catherine the Great (reigned 176296) prided themselves on introducing French culture and habits into their country. As a result, Russias premier museum takes its name from an aspect of country living which became popular in France in the seventeenth century and turned into a pan-European landscape gardening fashion in the eighteenth. A hermitage, with or without a hermit, sometimes in ruins and sometimes intact, was a required feature of a fashionably landscaped park of the Romantic era. When Peter began to build his great country palace of Peterhof, a seaside imitation of Versailles complete with fountains and garden pavilions, he naturally included a hermitage the first Russian Hermitage. It was a two-storey building with an upstairs dining room lined, edge to edge, with Dutch seventeenth-century paintings and Peter used it for private parties.