First published in Great Britain in 2016 by

Pen & Sword Aviation

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Ronald Lyell Munro 2016

ISBN 978 1 47387 275 2

The right of Ronald Lyell Munro to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Typeset in Ehrhardt by

Mac Style Ltd, Bridlington, East Yorkshire

Printed and bound in the UK by CPI Group (UK) Ltd,

Croydon, CRO 4YY

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways, Select, Transport, True Crime, and Fiction, Frontline Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Seaforth Publishing and Wharncliffe.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Introduction

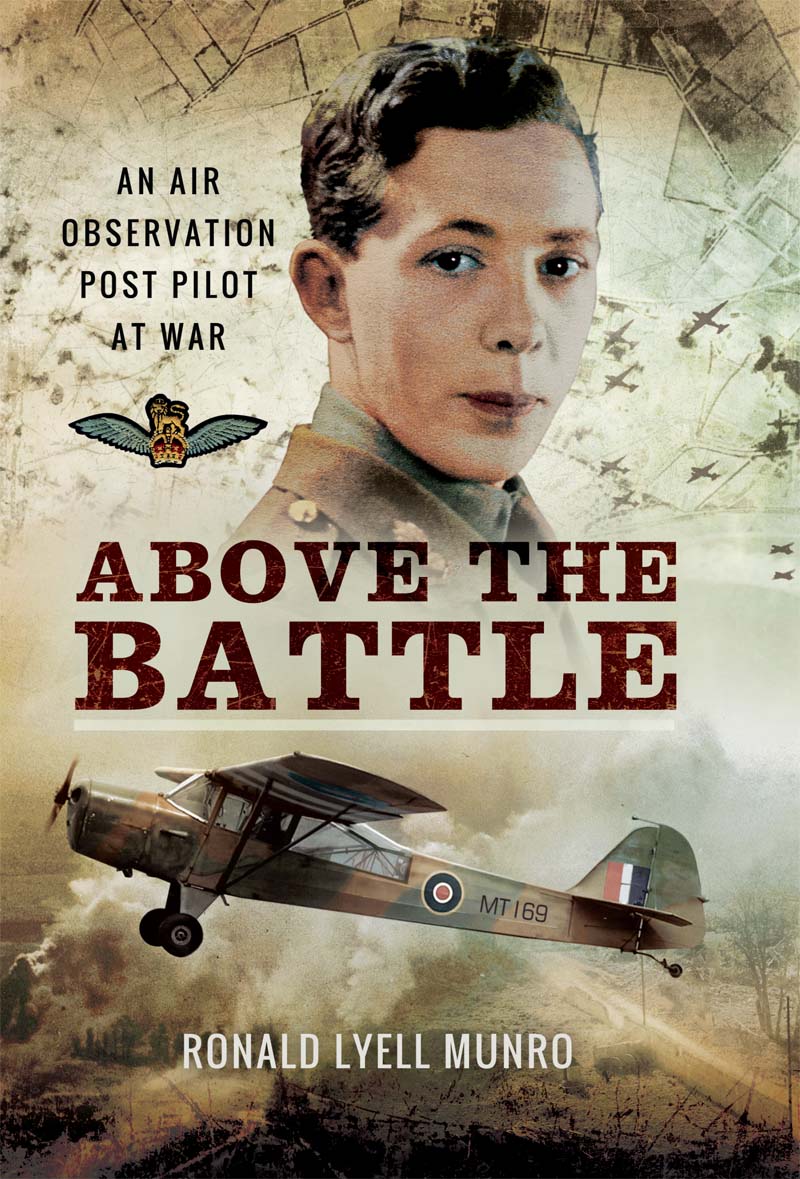

T his is the story of an Air Observation Post (AOP) pilots war in Europe. It is one of only two full accounts by British and Commonwealth pilots known to be in existence and, unless we are very lucky, there will be no more.

AOP pilots were the controlling eyes of the artillery and could direct devastating firepower onto the enemy formations over which they flew. They were expert gunners and pilots with the unorthodox flying skills their work demanded. The aircraft which had the characteristics needed for the role were Taylorcraft Austers; slow, unarmed and unarmoured, often flown so low that a parachute offered no chance of escape should things go wrong. From bitter experience, the enemy soon learned to dread their presence in the skies above the battlefield. German soldiers knew that an incautious movement, a puff of smoke or a chance flash of sunlight from a truck windscreen could bring tons of steel and high explosives raining down on them from the guns controlled by the pilot of the little monoplane circling like a buzzard, not far above them.

Usually flying alone, without fighter escort or radar warnings, an unwary AOP pilot was a sitting duck for enemy fighters. Like their Royal Flying Corps and Royal Naval Air Service predecessors of the First World War, they had to be constantly alert to what was happening in the skies around them as they directed the fire of the guns onto targets on the ground. Closing at over 250mph, an attacking Messerschmitt ME 109 or FW 190 left little or no time for indecision. Reactions had to be instinctive and evasive action instant. Failure was fatal.

Flying at low altitude made them easy targets for ground and anti-aircraft fire from the guns of an enemy keen to shoot them down before they could accomplish their mission. They were even at risk from the guns that they controlled. The intensity of artillery fire meant that, all too often, the path of the outgoing shells crossed the flight path of returning aircraft. Sometimes, the pilots luck ran out and they were shot down by their own guns.

Thanks to their unobtrusive role, with the noise of their aircraft engines drowned by the din of the guns, they were scarcely noticed by those on their own side, and in accounts of the battles in the long hard fight for Europes freedom their contribution is mentioned only in passing or, more often, not mentioned at all.

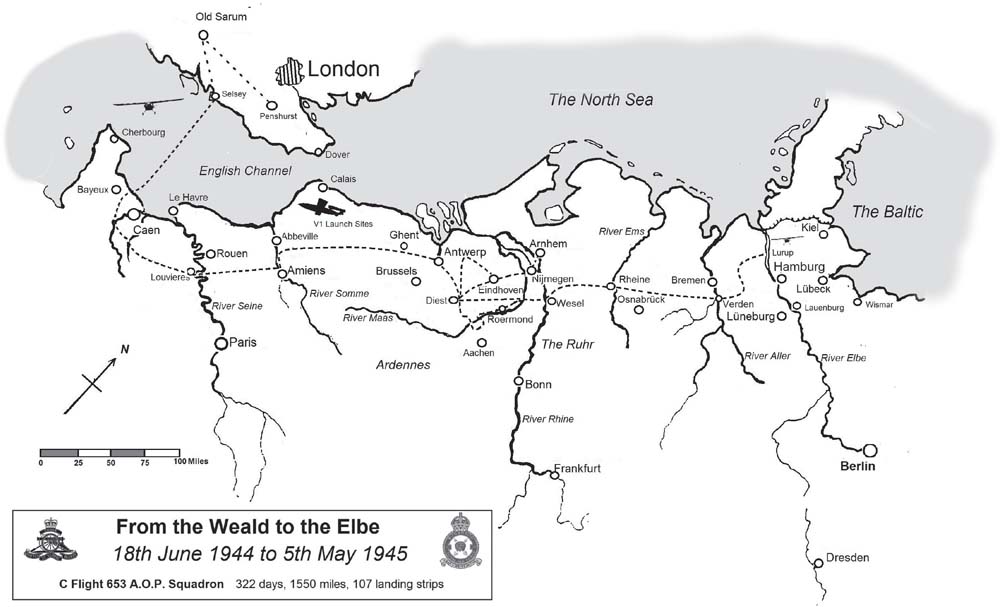

One of those AOP pilots was Captain Lyell Munro MBE. He first wrote about his experiences many years afterwards, partly for his children and partly because he wanted to make sure that what he and his comrades of 653 AOP Squadron achieved would not be forgotten. Only he and another pilot, Major Andrew Lyell of 658 AOP Squadron, have told their stories and now none survive.

Lyells own account starts in April 1943, on the day he arrived for duty at an airfield in wartime England; it ends three years later amidst the ruins of a defeated Germany. It is drawn from the memories, diaries and the active encouragement of his friends and former fellow pilots. From the start, his intention was not simply to record his own exploits: he wanted to pay tribute to his comrades in the Squadron who he hoped would read it. He therefore left out much that he considered to be too personal or which might bring back memories that were best forgotten.

When the first draft was sent years ago to the chosen publishers, they pointed out that, good story as it was, it needed more. They suggested he add something about himself and his post war life, including how the book came to be.

Lyell began to make the additions to his book but his time ran out and he did not complete them. After his death in 2002, his children and his nephew, Squadron Leader Alan Munro RAF (Retd), decided to finish the job. To give the full story, we have added material that provides both the beginning and end of his story and also adds much else that he wrote at the time of the main events. The opening part of the book includes a very early record of his experiences, possibly started as a journal. Much of this writing precedes Above the Battle and gives his immediate and personal impression of his flying training, his first experience of combat and above all what it felt like to be an AOP pilot. To read it is to hear Lyells voice as a thoughtful and determined young man preparing for a very great and highly dangerous adventure.

The second part is the manuscript as he wrote it. Many years have passed since then and it is very likely that todays readership will not share the knowledge or experiences he took for granted. Wherever it seemed possible that todays reader might find references obscure or puzzling we have added explanatory footnotes. We have also added excerpts from letters written by him to his fiance Jean. They add a sense of his feelings at the time as well as throwing light on one or two incidents that the original manuscript glosses over.

The final part, taken from Lyells letters, family history and the recollections of his children and his nephew, tells of Lyells career after the war and in later life.

Whilst completing the story, we have been guided by Lyells wish that this book should be as much about his comrades as about himself. On the flyleaf of the original manuscript, he wrote this quotation from another veteran who fought across the same landscapes, long ago: