Contents

Kodansha America, Inc.

575 Lexington Avenue, New York, New York 10022, U.S.A.

Kodansha International Ltd.

17-14 Otowa 1-chome, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 112, Japan

First paperback edition 2003

First published in hardcover in 1995 by Kodansha America, Inc.

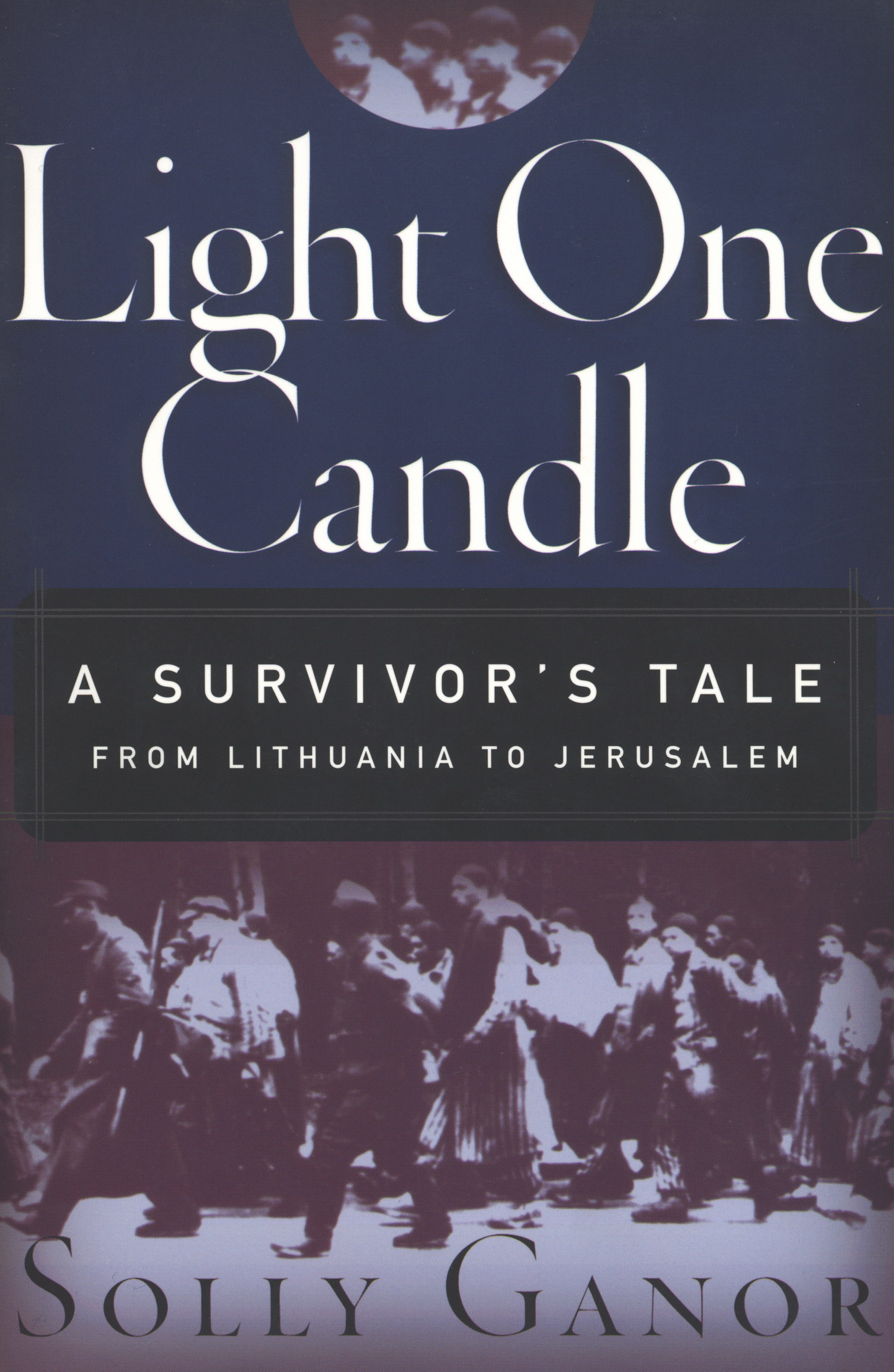

Copyright 1995 by Solly Ganor.

All rights reserved.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Ganor, Solly, 1928

Light one candle : a survivors tale from Lithuania

to Jerusalem / Solly Ganor.

p. cm.

ISBN 1-56836-098-3

ISBN 1-56836-352-4 (pbk.)

1. JewsPersecutionsLithuaniaKaunas. 2. Holocaust, Jewish (1939-1945)LithuaniaKaunasPersonal narratives. 3. Ganor, Solly, 1928. 4. Kaunas (Lithuania)Ethnic relations.

I. Title.

DS135.L52K384 1995

940.531809475dc20 9520720

Ebook ISBN9781568364537

v4.1

a

For my mother Rebecca and brother Herman,

and all those who perished during the war.

For my father Chaim and sister Fanny,

and all those who helped me survive the Holocaust years.

For Chiune Sugihara, Clarence Matsumura,

and the men of the 522nd Field Artillery Battalion,

my guide and my rescuers.

For my wife Pola and children, Leora and Danny.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to express my gratitude to Eric Saul, Lani Silver, and the dedicated volunteers of the Holocaust Oral History Project of San Francisco, for helping me confront my past. Thanks also to Yukiko Sugihara and family, for helping restore my faith in humanity.

Grateful acknowledgment goes to my fellow survivors: Uri Chanoch, David Granat, Aba Naor, David Levine, Chaim Konwitz, Arie Ivtsan, Zwi Katz, and the many others who helped me to remember clearly the Holocaust years. Thanks to George Oiye for the valuable information on the 522nd Field Artillery Battalion and to Lea Eliash for her memories of Kaunas.

Thanks to the Japanese American National Museum of Los Angeles, the National Japanese American Historical Society of San Francisco, the Simon Wiesenthal Center, and the Museum of Tolerance for valuable information.

Thanks also to Minato Asakawa, Philip Turner, and Joshua Sitzer at Kodansha for all their help and advice. Lastly, a very special and heartfelt thanks goes to Kathy Banks for the many hours of hard work and tender care she put into helping shape this book.

Two diaries have been of invaluable help in checking facts and dates: Josef Gars The Holocaust of the Jewish Kovne, published in Munich in 1948 and now out of print; and Avraham Torys Surviving the Holocaust: The Kovno Ghetto Diary, edited by Martin Gilbert (Harvard University Press, 1990).

PROLOGUE

Kaunas, Lithuania, is a littleknown spot on the map for most Americans. It looms large in my memory, however. It is where I spent the greater part of my childhood, and where a large part of the story that follows takes place.

In Lithuania, Kaunas has been known as the provisional capital of the country ever since 1920, when Poland annexed Vilnius during the RussoPolish war. A minor war, by later standards, and only one of many struggles that have torn the Baltic states over the centuries. In Lithuania you dont have to look far for reminders of the bloody history. Kaunas itself is ringed by old forts, built around the turn of the century by a Russian Tsar. When I was about nine years old, around 1937, my friends and I were thrilled to stumble upon the skeleton of a Russian officer. He was in a cave in the woods surrounding Kalautuvas, a little resort town a few miles downriver from Kaunas. Around the earthly remains of this lonely soul, who died so far from home, we concocted a whole history full of dash and heroism and high tragedy.

By 1940 Vilnius was once again the capital of Lithuania, but Lithuanians continued to refer to Kaunas as the provisional capital. It was a lovely city of nearly 120,000 people. More than thirty thousand Jews lived and prospered in the town, my family among them. For many years Kaunas was one of the few places in Europe where the Jews were able to live nearly autonomously, and they built a strong community. Its Yeshivas attracted students from all over Europe. Its professionals and scholars and merchants played an important role in the towns economy. Its cultural life was diverse and sophisticated. I remember being very happy there.

I was eleven years old when Hitler marched into Poland. The weeks and months that followed were fearful ones, as news of atrocities against Polish Jews reached us and refugees began streaming over the border into Lithuania. The Nazis had begun their inexorable march across the face of Europe, and would soon put our old Tsarist forts to hideous use. The next six years would turn out to be far more terrible than even the grimmest pessimists among us could foresee.

In 1939 and 1940 Kaunas became a sort of way station filled with people desperately seeking asylum from the Nazis. They sought help from any country they thought might receive them. Most of them were denied and were turned away by one government after another, including the governments of the United States and Great Britain. The one official who offered the Jews of Kaunas any hope was the representative of a government which shortly became Germanys strongest ally. That man was the Consul of Japan, Chiune Sugihara, who risked his career, his honor, perhaps even his life, to save more than six thousand Jews.

In my memory of those years Sugihara stands out as a single light in a sea of darkness. My family, for various reasons, was not among the fortunate thousands he helped directly, but he remained an inspiration to me throughout the terrible years to comeyears spent in the Slabodke ghetto and in the camps of Dachau.

How strange and wonderful it was to recognize Sugiharas ethnic features again five years after I last laid eyes on him, and at the very moment of my liberation. His eyes, and even something of his smile were in the kind face of the G.I. who brought me back from the brink of death. For it was a Japanese American, or Nisei, who lifted me from a snowbank where German SS guards had left me for dead. The Nisei soldiers name was Clarence Matsumura, and he was with the 522nd FABNthe field artillery battalion of the famous 100th/442nd Combat Team, a regimentalsized unit composed entirely of segregated units of Japanese American troops. These men came both from Hawaii and from the mainland, and many were volunteers. They served on the bloody battlefields of Italy, France, and Germany. The 100th/442nd suffered more casualties and won more medals for its length of service than any other American unit in the war.

The irony is not lost on me that even as Clarence and his kinsmen were fighting and dying for the United States, many of their families were incarcerated in American detention camps. Along with all Americans of Japanese descent living on the West Coast of the U.S. mainland, the families of nearly half of these Nisei troops had been uprooted from their homes and businesses and sent to live in tar paper barracks in desolate areas. The United States called these detention centers relocation camps. Concentration camps under another name.