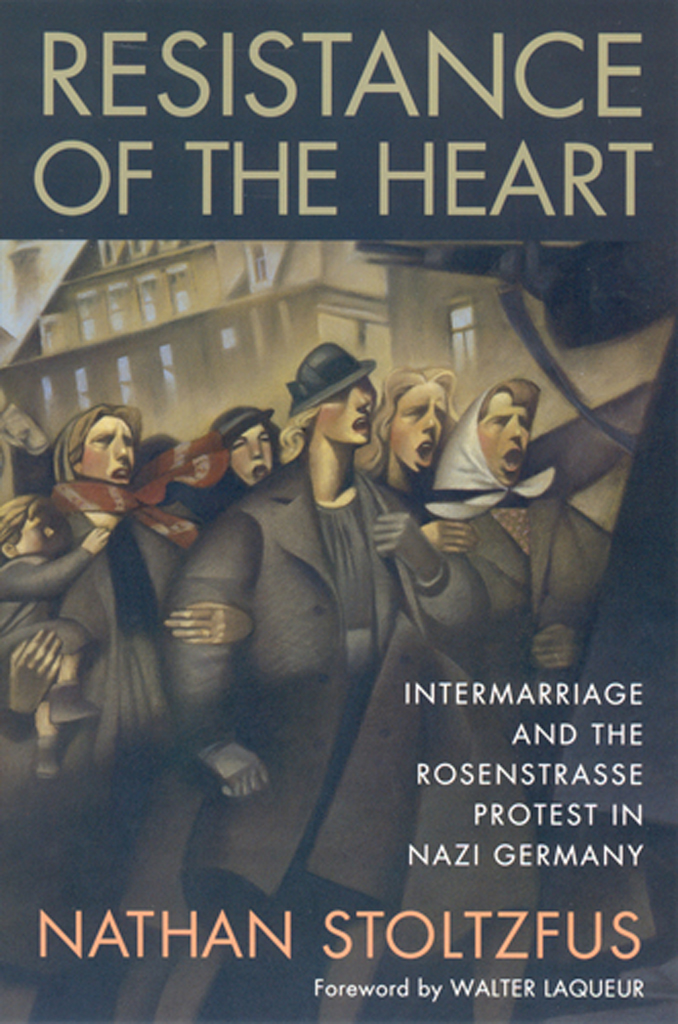

Originally published in hardcover by W. W. Norton, 1996

First published in paperback by Rutgers University Press, 2001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Stoltzfus, Nathan.

Resistance of the heart : intermarriage and the Rosenstrasse protest in Nazi Germany / Nathan Stoltzfus.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-8135-2909-3 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. World War, 19391945Jewish resistanceGermanyBerlin. 2. Interfaith marriageGermanyBerlinHistory20th century. 3. World War, 19391945GermanyBerlin. 4. Protest movementsGermanyBerlinHistory20th century. 5. Berlin (Germany)Ethnic relations. 6. JewsGermanyBerlinHistory20th century. 7. GermanyPolitics and government19331945. I. Title

DS135.G4 B476 2001

940.5318dc21 00062535

British Cataloging-in-Publication Data for this book is available from the British Library

Copyright 1996 by Nathan Stoltzfus

Foreword copyright 2001 by Walter Laqueur

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher. Please contact Rutgers University Press, 100 Joyce Kilmer Avenue, Piscataway, NJ 088548099. The only exception to this prohibition is fair use as defined by U.S. copyright law.

Manufactured in the United States of America

ISBN 978-0-8135-2909-7 (ebook)

A great deal has been written about the perpetrators of Nazi crimes during World War II and about the Jews, their main victims, but very little has been written about those considered in between, neither Germans nor Jewsthe Mischlinge, those of mixed Jewish and Aryan parentage. The same is true of those full Jews living in mixed marriages, who, despite being in the category of the main Nazi victims, represented 98 percent of officially registered German Jews who survived the war. Nathan Stoltzfuss fascinating and moving account deals with the terrible uncertainties facing the Mischlinge and intermarried Jews and with the bureaucratic wrangles that went on behind the scenes to decide who, ultimately, would be defined as Jewish.

The uncertainties of the mixed and intermarried Jews fate finally culminated in the dramatic Rosenstrasse protest in Berlin in February and March 1943a unique occasion on which the dreaded Gestapo was defied by a group of German women fighting for the liberation of their incarcerated husbands and sons. The facts of the protest have not been shrouded in secrecylike many other students of recent German history, I learned about the events and even described them very briefly in a semidocumentary accountbut Dr. Stoltzfus is the first to investigate the events leading to the protest systematically and in depth, not only on the basis of archival material but, more importantly perhaps, on the basis of interviews with surviving participants and eyewitnesses.

While Nazism was a murderous regime aimed at the physical annihilation of its internal enemies, it faced all along difficulties of conceptualization and definition. Who was a Jew? Who was a gypsy? Answers all depended on how far back one went in tracing Jewish blood. Both on the theoretical and practical level, Nazi policy was inconsistent, and there were frequent procedural changes. (At the time, as now, no one knew how many Mischlinge lived in Germany; estimates varied between 110,000 and 700,000, with the former figure probably closer to the mark.) Eventually, the Nuremberg Laws of 1935 established that those with less than one Jewish grandparent were not to be affected by the new legislation, except perhaps as far as possible membership in the Nazi party and its elite units such as the SS was concerned. But even though the Nuremberg Laws were clear on the identity of intermarried Jews, classifying them as Jews along with all others of three or more Jewish grandparents, these laws were not clear on many details and involved lengthy commentaries and interpretations that changed from time to time concerning Mischlinge.

The arbitrary use of the term Jew to refer to the Mischlinge persists to this dayhence the reference in sensationalist accounts to Jews who allegedly served as senior officers in the Wehrmacht. Most of these so-called Jews were actually quarter-Jews by the definition of the Nuremberg Laws (and sometimes not even this). But it is true that there were perhaps several hundred protected Jews (Schutzjuden) who, owing to their connections with very highly placed Nazi leaders or other personalities in Germany or abroad, were not affected by the final solution. Although their fate remains unexplored, it is known that none of them had been a member of the Jewish community and that virtually all of them were racially of mixed origin or had been made honorary Aryanslike (posthumously) the famous nineteenth-century physicist Heinrich Hertz of electromagnetic waves and Kilohertz fame. Hertz was the son of a baptized Jewish father and a Christian mother. His nephews, Gustav Hertz and the biochemist Otto Warburg, were sons of Jewish fathers; both were recipients of the Nobel Prize, and both survived undisturbed in Nazi Germany. But they, too, were Mischlinge, and their case shows that exceptions could be made.

Exceptions could also be made for full German Jews in intermarriage. An uncle of mine, for instance, survived because he lived in a mixed marriage. (According to Nazi regulations a household was considered Jewish if the man was Jewish, but not so if the wife was.) Another aunt survived because she had been married to an Aryan, who was killed in World War I. As the husband was no longer alive, she should have been deported and killed, but since her son was serving in the army she was spared. The son, my cousin Hans, was less lucky: he was killed on the very last day of the war, fighting in the city of his birth.

Since Nazism was a radical and fanatical movement, why did it bother to take account of these fine distinctions? Why did it not aim for the extermination of all those suspected of even a faint connection with Judaism? The answer, very briefly, is that the Nazis depended on a pseudoscientific race theory that was not quite unambiguous on the subject of Mischlinge. Furthermore they had to take into account, especially in wartime, the negative impact indiscriminate persecution of Jews in intermarriage would have had on public opinion, especially among influential circles of German society. For example, after 1933 it appeared that both Theodor Duesterberg, a one-time ally of the Nazis and the head of the Stahlhelm, the paramilitary right-wing organization, and Theodor Lewald, head of the German Olympic committee, were Mischlinge according to the Nuremberg Laws. However, it was one thing to force these public figures into retirement and quite another to deport them to Auschwitz. Those living in mixed marriages often had close relatives in the German middle class, and even among the aristocracy there were thousands of such people serving in the armed forces who would have been antagonized if relations of theirs, even if only by marriage, had been sent to extermination camps.