Published in the United States of America and Great Britain in 2011 by

CASEMATE PUBLISHERS

908 Darby Road, Havertown, PA 19083

and

17 Cheap Street, Newbury RG14 5DD

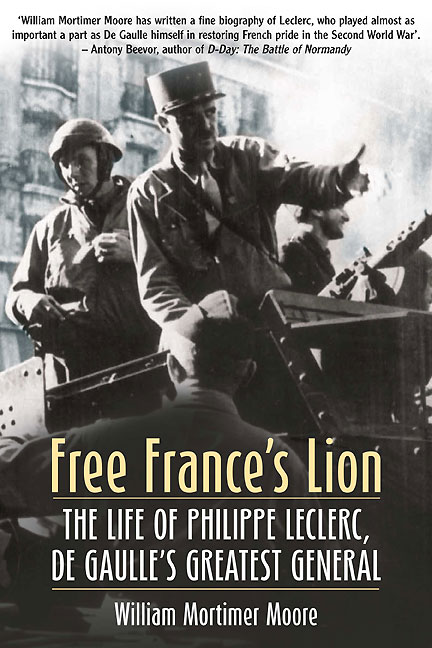

Copyright 2011 William Mortimer Moore

ISBN 978-1-61200-068-8

Digital Edition: ISBN 978-1-61200-080-0

Cataloging-in-publication data is available from the Library of Congress

and the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any

form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording

or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from

the Publisher in writing.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Printed and bound in the United States of America.

For a complete list of Casemate titles please contact:

CASEMATE PUBLISHERS (US)

Telephone (610) 853-9131, Fax (610) 853-9146

E-mail: casemate@casematepublishing.com

CASEMATE PUBLISHERS (UK)

Telephone (01635) 231091, Fax (01635) 41619

E-mail: casemate-uk@casematepublishing.co.uk

FOREWORD

O ne of the central and most tragic consequences of Frances defeat, surrender and occupation in 1940 was the range of practical and moral choices that confronted French soldiers of equal patriotism. The constantly changing complexities of real life seldom offer clearcut moments of decision between courses of action with predictable, black-or-white consequences. The continuum of French politico-military history between 1940 and 1962 shows many examples of individuals choosingunder the practical and emotional pressures of the moment, and often for uncynical motives paths that would lead them into unanticipated positions. The malign consequences of these choices could spoil (or even end) lives, and created spirals of hatred that lasted for more than the next generation.

In the English language there are few accounts of that period that are thorough enough to carry us back beyond the easy conclusions of hindsight, and thus to correct any hasty tendency to judge the men who shaped it in simplistic terms. This book is one of themalthough it must be said at once that one of the authors advantages, and the readers pleasures, is that its subject was as unambiguously admirable as any of the leading figures in French affairs during the 1940s. Philippe de Hautcloque, remembered by his nom-de-guerre of Leclerc, was not only an honourable and skillful soldier, but also an attractive personality.

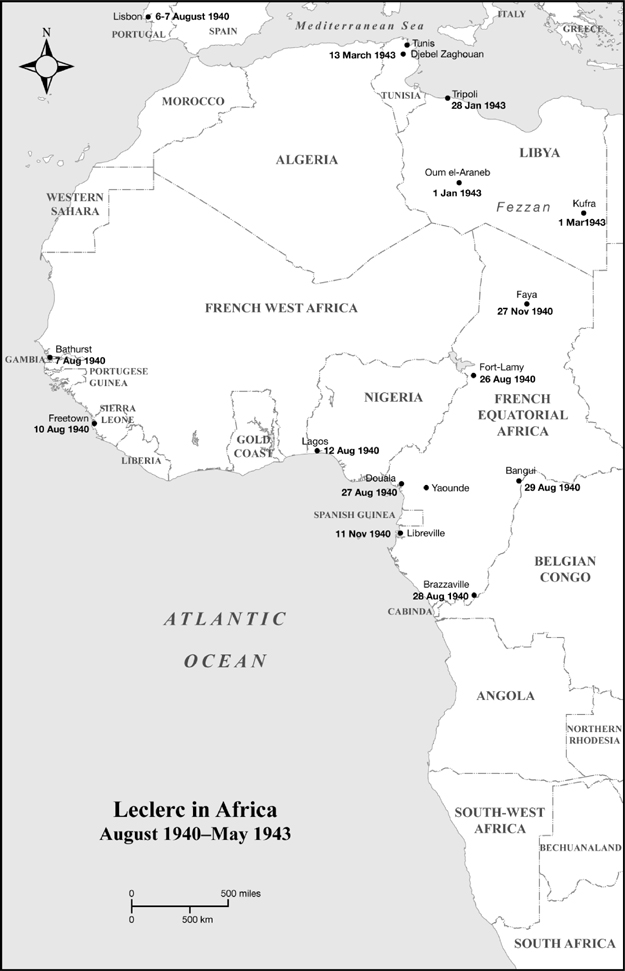

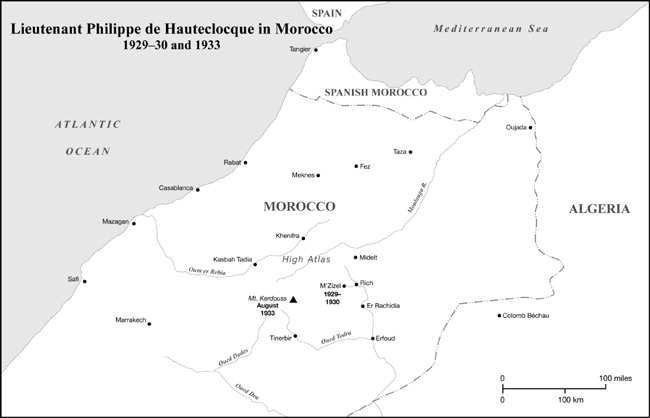

Wounded during the Battle of France in spring 1940, he twice escaped German captivity by exercising nerve and physical daring. He was of exactly the class and milieu to which Marshal Ptains Vichy regime, established in late June, should have had its strongest appealindeed, the extended de Hautcloque family was itself divided in its loyalites; yet when he was told of General De Gaulles broadcast from London, Leclerc unhesitatingly decided to risk everthing for the splendid but then-tiny flag of Free France. By August 1940 he was leading half-a-dozen men on a James Bond mission in French West Africa, and by the end of that year he was organizing the first raids against the Italians in southern Libya, in co-operation with the British Long Range Desert Group. For the next two years, drawing upon his early experience of colonial soldiering in southern Morocco, he pursued the often frustrating task of building up a multinational Free French brigade in this remote and fly-blown pre-Saharan backwater, and sending it into battle in realistic increments. It was a task that demanded, and revealed, all his energy and intelligence, and the charismatic powers of leadership that enabled him to forge an effective group of subordinates from a wide spectrum of backgrounds, from Catholic aristocrats like himself to brawlers like the future paratroop general Jacques Massu.

When, in January 1943, Leclerc led his brigade northwards to join British Eighth Army in Tripolitania, this proud Frenchman even managed to cement a tolerably good relationship with the blindly undiplomatic General Montgomery. He was unshaken in his loyalty to De Gaulle during the intensely difficult period following the Anglo-American landings in French Morocco and Algeria, which led to bitter hostility between the Gaullists of the first hour and Vichys French African Army. In August 1944 it was Leclercs 2nd Armoured Division that was given the honour of liberating central Paris, and by VE-Day his prestige among the Fighting French was unrivalled, despite the more senior command held by Jean de Lattre at the head of troops who had mostly only got back into the war on the right side in early 1943.

While Leclerc was as decisive as any successful officer must be, one of his rarer qualities was the ability to change his opinions when they were contradicted by experience on the ground. He displayed this quality most strikingly during his senior command in French Indochina in 1946. Unlike General De Gaulle, his experience of soldiering in co-operation with the British and Americans in World War II had not left Leclerc with the formers often paranoid suspicion of the Anglo-Saxons, and he was able to work constructively with Admiral Mounbatten in 1945. Nevertheless, he was at first unable to share British scepticism about the recreation of the pre-war white colonial empires in Asia, and he landed in Saigon determined to achieve as much as he could for De Gaulle. He achieved a good deal, despite his inadequate military resources; but he also proved himself open to arguments and analysis from a number of quarters, both French and Indochinese.

It takes a most unusual soldier to move beyond the aggressively patriotic instincts that have served him well in the past, and to develop a clear-eyed, long-term view of the political dimensions of his theatre of operations and this, while men under his command are actually fighting and dying. That Leclercs heartfelt advice to his successor Emile BollaertNegotiate; above all, negotiatewas in the end to come to nothing condemned France (and after her, the United States) to decades of costly sacrifices, for no eventual reward. Leclercs premature death in late 1947 robbed France of an intelligent, faithful and upright servant, whose prestige might have given weight to advice that a succession of weak governments would sorely need during the 1950s.

The authors research into a life lived among the movers and shakers of a period of great complexity has been admirably deep and wide, and he presents his clear, fair-minded and balanced conclusions in an extremely readable text, full of insights into the characters and relationships that shaped the events that he unfolds. This book is the work of a fine historian and a fine writer.

MARTIN WINDROW

Author of The Last Valley: Dien Bien Phu

and the French Defeat in Vietnam