Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For Grace and Forrister

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This book began three decades ago when I first opened a copy of Fighting the Flying Circus as a boy. Eddie Rickenbackers exhilarating tale of biplanes dueling in the skies of World War I kindled not only a strong love of history but a desire one day to tell these stories myself. I have room here to thank only a small fraction of those who have helped me on this long journey from dream to finished manuscript.

One of the great benefits of writing is that it enables me to meet people that might not otherwise cross my path. I spent a recent afternoon, for instance, with Carlton Pate III, who cheerfully sat me in the seat of his meticulously restored Ford Model C and calmly instructed me as I careened around the back streets of suburban Connecticut. Or Ted Hamady, an independent aviation historian, who patiently answered all my questions about the Nieuport 27 and SPAD XIII, on occasion pulling out pieces of them to illustrate a point about design and construction. And I spent a pleasant day with the members of the mid-Atlantic chapter of Over the Front, the League of World War I historians, who generously opened me up to new worlds about not only early airplanes but how innovation and necessity so often work hand in hand.

No book of this nature would be possible without the assistance of many archivists, researchers, and librarians. My deep appreciation goes to the archivists and researchers at Auburn University Libraries, which houses the single largest collection of Rickenbacker materials: Dwayne Cox, in charge of the Special Collections and Archives; John Varner, Tommy Brown, and Midge Coates, digital projects librarian. Many thanks to the staff at the Library of Congress, particularly manuscript reference librarian Bruce Kirby. At the National Archives and Records Administration in College Park, Maryland, archivist Eric van Slander and archives specialist Theresa Roy proved particularly helpful. Id like to thank museum specialist Brian Nicklas at the Smithsonians National Air and Space Museum. Also my gratitude goes out to Paul Barron at the George C. Marshall Foundation; Mary Marshall Clark, Columbia Center for Oral History, Columbia University; Karim Hussain, Modern Domestic Records, the National Archives, UK; special collections archivist Becki Plunkett, the State Historical Society of Iowa; archives technician Sylvester Jackson Jr., Air Force Historical Research Agency, Maxwell Air Force Base; assistant curator Rebecca Jewett, Rare Books and Manuscripts Library, the Ohio State University Libraries; John Pulford, head of collections and interpretation, Brooklands Museum, UK; manuscript curator Bert Stolle, the National Museum of the United States Air Force; Sarah Swan, U.S. Air Force Museum at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base.

For reading the manuscript at various stages and offering critical insight, Id like to thank William Casey, Joe Meany, Alexis Doster III, Larry OReilly, Dick Hallion, Duke Johns, and Tom Crouch. Cindy Scudder gave indispensable help with picture research and design, not to mention her good counsel about publishing. Thanks to Cathi and Phil Smith, not only for assembling tiny biplane models and finding a recipe for French 75s, but for their enthusiastic support and friendship. And thanks also to the often brilliant essayists of the Literary Society of Washington, upon which I tried out many new ideas. Im particularly indebted toand honored to count as a friendTim Dickinson, whose guidance and long, rich conversations about all things Rickenbacker both sustained and stretched my thinking in many new directions.

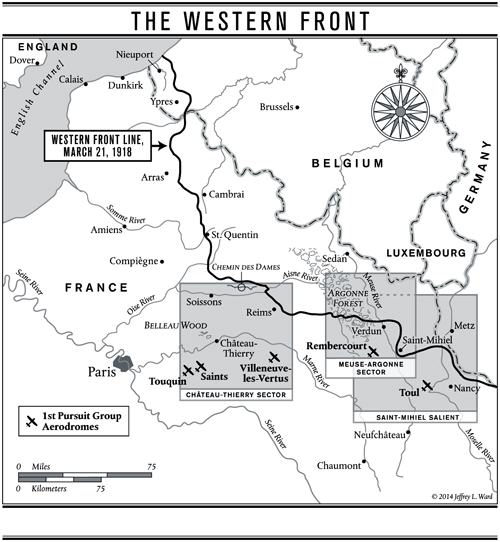

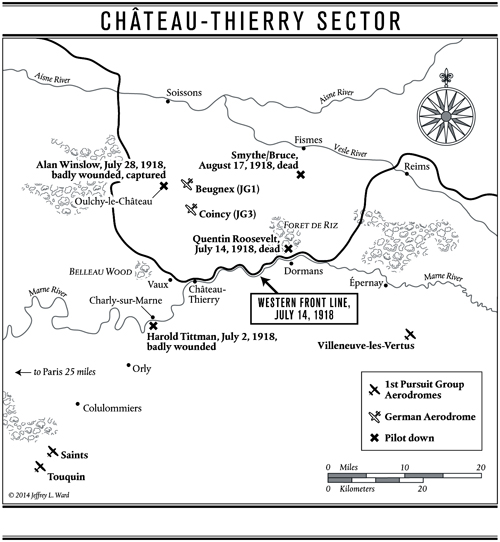

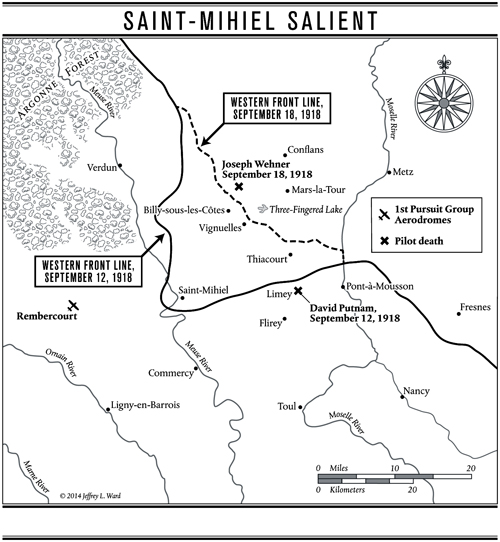

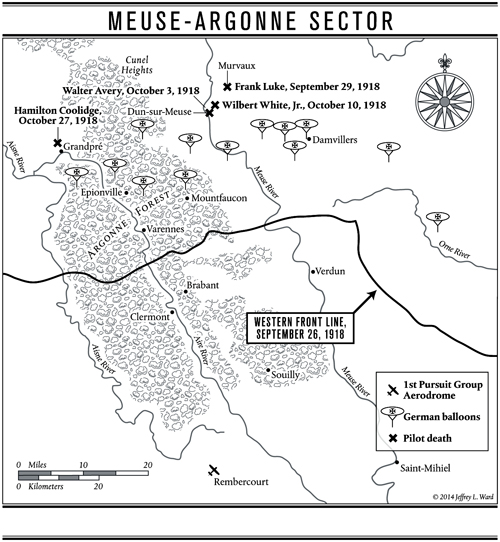

My editor at St. Martins Press, Marc Resnick, believed in this project enthusiastically from the beginning, and navigated the projects many curves with a sharp editorial eye, good judgment, and a great sense of humor. His backup, Kate Canfield, always proved up to the task at hand. Id also particularly like to thank SMPs indomitable director of publicity, John Murphy, and ever-competent and energetic senior publicist Christy DAgostini. My warm thanks also go out to Jeff Dodes, Dori Weintraub, Laura Clark, Michael Hoak, and Kathryn Hough. My thanks also to copyeditor India Cooper, cartographer Jeffrey L. Ward, and indexer Peter Rooney.

I couldnt have a better agent in Stuart Krichevsky. Without his wisdom, clarity, enthusiasm, excellent judgment, and market savvy this book would not have happened. Im also deeply grateful to Stuarts colleagues Shana Cohen and Ross Harris.

To my parents, Jane and Phil, and my brother, Jim, who have always, always been there. And to my children, Grace and Forrister, to whom this book is dedicated. The joy they give me is a constant source of my inspiration. And to my wife, Diana. It is impossible to imagine a writing life without her warm support, presence, and sagacity. I truly won the lottery when I met her.

INTRODUCTION

WHEN A MAN FACES DEATH

One bright spring afternoon in May 1918, a column of German infantry halted on a muddy road in northeastern France, craning their necks skyward as four biplanes locked in mortal combat. More like butterflies than human creations, their double wings bobbed and dipped capriciously. For long moments, the men forgot their blistered feet and aching shoulders to marvel at the seeming effortlessness of these airborne gladiators.

In his cockpit high above, the twenty-seven-year-old Eddie Rickenbacker fought for his life in a machine that battered his body at every turn, delivering a disorienting cocktail of dizziness, vertigo, nausea, pounding noise, extreme cold, and, always, fear. Only fifteen years downwind from Kitty Hawk, these aircraft were little more than controllable box kites with engines, flimsy contraptions of wood, fabric, and baling wire so insubstantial as to appear dangerous just sitting on the ground.

Half an hour earlier he had left his aerodrome on patrol, taking some twenty minutes to reach 17,000 feet, the air thinning to where he struggled to breathe. His head grew light, his vision tunneled. (Oxygen deprivation so fogs judgment that the Federal Aviation Administration today prohibits flights above 10,000 feet without pressurized oxygen.) As he climbed, his Nieuports rotary engine spattered him with castor oil, which he could not help but inhale, churning his stomach and loosening the bowels. Nausea stalked him relentlessly, often drenching his cockpit in vomit. His fur-lined teddy-bear suit afforded little protection against temperatures that dropped well below zero in the unheated, open cockpit. Pilots would often find themselves peeling their stiffened, numbed right-hand fingers off the joystick one by one.