Contents

Guide

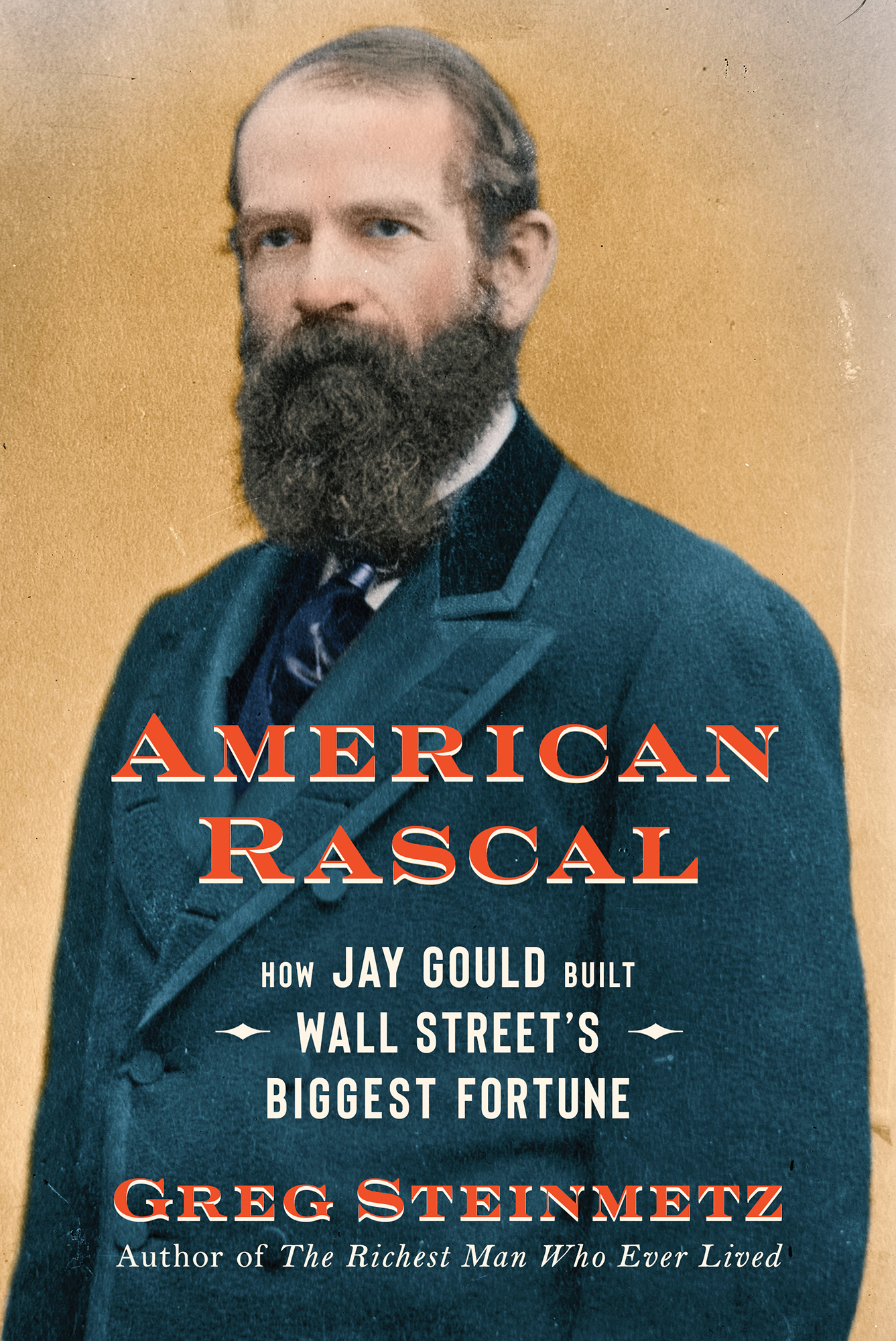

American Rascal

How Jay Gould Built Wall Streets Biggest Fortune

Greg Steinmetz

Author of The Richest Man Who Ever Lived

For our children: Axel, Anya, Jasper, and Alta

I NTRODUCTION

O n a warm April afternoon in 1873, the financier Jay Gould took time off from counting his money to have lunch at Delmonicos, the fanciest restaurant in town. While he was eating, a lawyer walked over to his table, cocked his fist, and punched him in the face.

A series of spectacular financial triumphssome said swindleshad made Gould fabulously rich. Now, at age thirty-six, he was the most notorious businessperson in the country. Like others who tried to claw back money from Gould, the lawyer was getting nowhere in court. The laws were too weak, enforcement too lax, and the judges too crooked. Gould had them in his pocket.

Oysters and Veuve Cliquot were the rule at Delmonicos. The biftek was served au naturel. For most people, a meal cost a weeks wages. For the rich, it was a place to enjoy their wealth, not pick fights. Joseph Marrin, the lawyer, didnt care. Frustrated to the point of rage, he took justice into his own hands and clocked Gould in front of the lunch crowd. In a piece called Goulds Nose, The New York Times declared Marrin a hero and worried about a pileup if others followed his lead. The flattening of Goulds nose, it wrote, would be an incidence of hourly occurrence.

This book seeks to explain Jay Gould and his underappreciatedand aggressively malignedrole in the countrys transformative economic expansion of the nineteenth century. But it is just as much an exploration of Wall Street during its Wild West era after the Civil War when, by the rough means on display at Delmonicos, the seeds of our current financial system were planted. Stock and bond markets were hitting their stride. Only the strictures of conscience, rather than law and regulation, governed the participants. That left the unscrupulous free to self-deal, fix prices, trade on inside information, lie to investors, and manipulate stock prices. Out west, Jesse James and other train robbers stole your wallet. In New York, men in top hats, abetted by corrupt politicians, snatched your life savings.

The state of play was tolerated. It was an objectionable by-product of progress. Sure, there were cunning moneymen who abused the system. But that was a side effect, the price of opportunity. After all, it was Wall Street that raised the money to build railroads, to settle the plains, to create jobs, and to elevate living standards. The bankers and investors at the corner of Wall and Broad had their faults, but they were making America the most powerful nation on earth and its people the most prosperous.

A few people, the men the writer Matthew Josephson condemned as Robber Barons, amassed spectacular wealth. Cornelius Vanderbilt, John D. Rockefeller, and Andrew Carnegie come to mind. But they arent the focus of this book because they made their money in industry, not in finance. Vanderbilt toiled in steamships and railroads, Rockefeller in oil, and Carnegie in steel. Only the lesser-known figure of Jay Gould, as rich as any of them and another of Josephsons scoundrels, was foremost a creature of Wall Street.

To the extent Gould is remembered, it is for Black Friday, the day he blew up the gold market and paralyzed the financial system. For this and other bold and sometimes undeniably felonious acts, lawyers swamped him with suits, prosecutors hit him with subpoenas, and Congress hauled him in for hearings. This was as far as things got. Arrested three times, Gould never spent a day in jail. In a better world, he would have. But these were raw times. Frustrated opponents, like the lawyer at Delmonicos, turned to vigilante justice. One victim tossed Gould down a stairwell. Another pulled a gun on him. During the contested presidential election of 1884an election in which Gould was believed to have interfereda lynch mob marched on his Broadway office. As they waited in hope of spotting their prey, they riffed on the Battle Hymn of the Republic. Out went Glory, Glory Hallelujah. In came Hang Jay Gould on the sour apple tree. For them there was no doubt. Gould deserved the noose. Jay Gould was the mightiest disaster which has ever befallen this country, wrote Mark Twain. The people had desired money before his day, but he taught them to fall down and worship it.

For Twain, Gould was the biggest robber of the barons. It was one thing to clean up at the poker table when you played by the rules. It was another to cheat. Gould, he argued, was a champion cheater. Even worse, he was an inspiration for others inclined to cheat. He showed that no act of financial villainy was too bold. The publisher Joseph Pulitzer saw Gould the same way as Twain. Convicts will wonder, wrote Pulitzer, what mental defect robbed them of such a career as Goulds.

Goulds peers were more charitable. Gould stood not much over five feet tall. But to those who appreciated his gifts, the Little Wizard, as the newspapers called him, was a giant. Vanderbilt told a Syracuse newspaper that Gould was the smartest man in America. They recognized Gould as a master of his craft. Ruthless? Yes. A liar? Maybe. It depended on the definition. But no one disputed that he was an extraordinary problem solver, an unparalleled negotiator, an expert communicator, a lightning-fast thinker, and a masterful tactician with a staggering memory. He knew the numbers better than his accountants. He knew the law as well his lawyers. When it came to business, Gould had it all.

Gould complemented his natural endowments with nerves of iron and a work ethic, even as a teenager, so strong that it damaged his health and, quite possibly, shortened his life. With his mix of brains and single-mindedness, he was suited to make the most of the moment. Goulds friends thought he got attention for the wrong reasons. They cited his talents and wondered why he never seemed to win praise. Why is Rockefeller held in so much higher esteem than Gould in the public mind? asked the banker Jesse Seligman.

Gould, of course, didnt see himself as a crook. He bribed politicians because his competitors bribed politicians. Equally, he made his money not at gunpoint but by manipulating others to make bad decisions. They would pay him too much when he was selling or accept too little when he was buying. Gould would say his victimsthose on the other side of his tradeshad only themselves to blame. If someone was too lazy to read the fine print, too greedy to consider the downside, and too dumb to watch what Gould did rather than what he said, they deserved their fate. Gould feasted on other Wall Street professionals. They were trying to do to him what he did to them. Did that make him a crook?

G OULD WAS ONE of the most famous people of his time. During an 1886 labor dispute, his name appeared on the front page of The New York Times every day for a month. Such was Goulds reputation that the public assumed, wrongly, that he could single-handedly move the market. Such was Goulds notoriety that once, after a train robber picked clean every passenger on a Texas train, the crook told the onboard postal clerk that he would leave him alone, saying he wasnt after the governments money, only Jay Goulds.

These days, Gould is all but forgotten. In 2019,