Published by Haunted America

A Division of The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2016 by Hali Keeler

All rights reserved

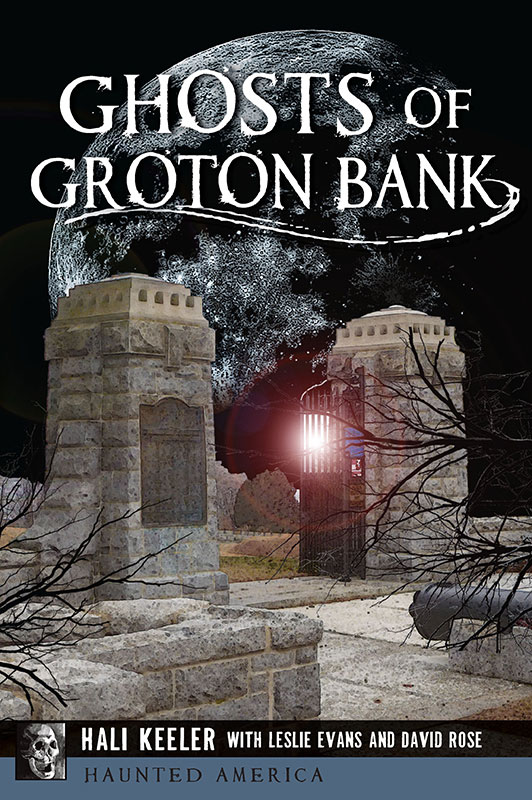

Front cover: The entry gates at Fort Griswold. Courtesy of Gerry Keeler.

First published 2016

e-book edition 2016

ISBN 978.1.62585.744.6

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016934654

print edition ISBN 978.1.46711.961.0

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Of all the properties in Groton Bank that are of historical importance, the Amos Prentice House on Thames Street, also known as the Mother Bailey House in honor of its most colorful and famous occupant, is in the most extreme state of disrepair. Having been in private hands for decades, it has been virtually ruined by thoughtless renovations and careless tenants. It was bought by the City of Groton to save it from further deterioration and remains empty. The house, including the famous tavern in the basement, needs complete restoration, from a purely structural perspective to an eventual esthetic one.

Some of us in the community thought that if we could just paint the downstairs rooms, hang some period artwork and furnish it lightly with some historically accurate pieces, it could be open to the public on a limited basis for tours, which would create some revenue. However, the structural engineers have deemed the building too unsafe even for that. The ghost tours have raised a few hundred dollars, but that is a drop in the bucket.

Therefore, we dedicate any royalties from the sale of this book to the future restoration of this important house and look forward to the day when it can take its rightful place among the active historic house museums in southeastern Connecticut.

PREFACE

Groton is an area of about seven square miles bordered on the east by the Mystic River, the west by the Thames River and the south by Fishers Island Sound. Its history has been chronicled in detail by Carol Kimball, the late town historian of Groton. The depth of her knowledge and the breadth of her collection have provided extensive resources. When she passed away in 2010 at the age of ninety-four, her estate contained boxes and files of research, clippings, notes, books and artifacts that have not yet been entirely catalogued. It is a treasure-trove of historical information, much of which was given by the family to the Groton Historic Society. Jim Streeter, the current town historian, also has a collection of boxes and closets and rooms filled with his own research. Between the two of them, there is very little that is not known about the history of Groton. I am relying on the fruits of their combined efforts to create this preface.

Grotons beginnings can be traced to 1646, when John Winthrop Jr., son of the governor of Massachusetts, settled on the Thames River and established what he called the Pequot Plantation. According to The Groton Story, by Carol Kimball, in June 1646, it was recorded in Governor Winthrops journal that a plantation was begun this year at Pequod river by Mr. John Winthrop, Jr., Mr. Thomas Peter, minister, and this court power was given to them two for ordering and governing the plantation until further order, etc.

This settlement extended to both sides of the river, but the east side was originally used for grazing cattle. In 1647, John Winthrop Jr.s family came from England to live in a large house in Pequot Plantation. He also was granted land on the east side of the river; this was considered the best farmland in town. Later that year, other plots of land where given by lottery, and families were attracted to the good land of Poquonnock Plains, a fair distance from the river on the east side. One of these plots was described as a parcel of land between the west side of the Mystic River and a high mountain of rocks. Another was described as where the wigwams were in the path that goes from his house toward Culvers among the rocky hills. (Edward Culver had a farm nearby). If it sounds like there were a lot of rocks, ask anyone who has tried to put in a lawn or garden in this area. Rocks seem to spontaneously generate around here. To be fair, though, we have an abundance of beautiful old stone walls, which didand continue tomake good fences.

In 1657, after eleven years of petitioning, John Winthrop Jr., recently elected the third governor of Connecticut, quickly convinced the General Court that Pequot Plantation should be renamed New London.

Meanwhile, the problem was that although everyone was required to attend church services on the Sabbath, the only church in New London was on the west side of the river. This presented a problem for the families on the east side of the settlement, as roads were not very good, and even in poor weather they were forced to cross the river on the ferry. A ferry, at that time, was basically a scow-type, flat-bottomed boat that operators poled, rowed or sailed across the water. It was both dangerous and uncomfortable, but it was the only way to cross a river in the 1600s. Around 1687, James Avery, who was settled on the east side of the river, pleaded for separation from New London, as at that time twenty-eight families were living there. He asked that they be allowed to have their own church, which was at the heart of the problem. After nine years, they were allowed to have the minister come to the east side for church servicesonly once every third Sunday in inclement weather! Finally, in 1696, they were permitted to organize their own church, and in 1703, their meetinghouse was built. In 1705, the General Assembly approved and granted a charter to the lands on the east side of the Thames River. They were given full independence from New London. It is commonly believed that they called their new town Groton, after the Winthrop estate in England. (However, not everyone was pleased with that; some preferred the names Southwork or East London.) Whatever they called it, New London had the last word by demanding payment for the financial loss this would cause and ownership of the ferry.

Back to the church: the first one was Congregational, the established church of colonial New England. By 1704, some families were petitioning for a Baptist church, and consequently, Groton became home to several more Baptist, as well as Methodist, Episcopal and Lutheran, churches.

Once again, according to Kimballs The Groton Story, no sooner had the ink dried on the charter than a town meeting was called in 1706 to create a school. By 1766, all Connecticut towns were divided into school districts in order to receive a portion of public funds. There were numerous one-room neighborhood schools that children would attend. In 1864, school was in session in the summer and winter. By 1872, there were eleven districts: Groton Bank, North Lane, Center Groton, Burnetts, Mystic River, Upper Noank, Pequonnoc, Shinnicossett, Flanders, West Mystic and Noank. By 1929, there were twelve schools. There was no high school. By 1963, there were sixteen elementary schools, three junior high schools and one senior high. Sadly, today, there are only seven elementary schools, two middle schools and one high school.