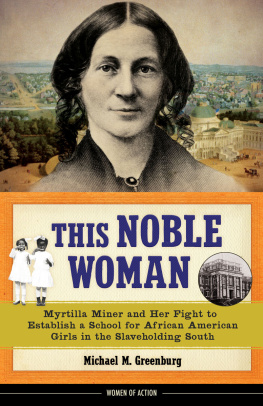

From This Noble Woman:

On December 3, 1851, Myrtilla cast off her fears and the doubts of others and opened her School for Colored Girls, as it came to be known, with six free African American students in attendance. She no doubt began class with a brief introduction of who she was and then described what she expected from her students. Her stern yet caring approach to education would have been apparent from the moment she spokeas well as her unwavering commitment to equality. She explained to the class that the color of their skin had nothing to do with their ability to learnbut that attitudes in the community and the country as a whole would require that they work harder and show more restraint than white schoolchildren. Be as wise as serpents and as harmless as doves, they were taught.

OTHER BOOKS IN THE WOMEN OF ACTION SERIES

Bold Women of Medicine by Susan M. Latta

Code Name Pauline by Pearl Witherington Cornioly, edited by Kathryn J. Atwood

Courageous Women of the Civil War by M. R. Cordell

Courageous Woman of the Vietnam War by Kathryn J. Atwood

Double Victory by Cheryl Mullenbach

The Many Faces of Josephine Baker by Peggy Caravantes

Marooned in the Arctic by Peggy Caravantes

Reporting Under Fire by Kerrie L. Hollihan

Seized by the Sun by James W. Ure

She Takes a Stand by Michael Elsohn Ross

Women Aviators by Karen Bush Gibson

Women Heroes of the American Revolution by Susan Casey

Women Heroes of World War I by Kathryn J. Atwood

Women Heroes of World War II by Kathryn J. Atwood

Women Heroes of World War IIthe Pacific Theater by Kathryn J. Atwood

Women in Blue by Cheryl Mullenbach

Women in Space by Karen Bush Gibson

Women of Colonial America by Brandon Marie Miller

Women of Steel and Stone by Anna M. Lewis

Women of the Frontier by Brandon Marie Miller

A World of Her Own by Michael Elsohn Ross

Copyright 2018 by Michael M. Greenburg

All rights reserved

First edition

Published by Chicago Review Press Incorporated

814 North Franklin Street

Chicago, Illinois 60610

ISBN 978-0-912777-09-2

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Greenburg, Michael M., author.

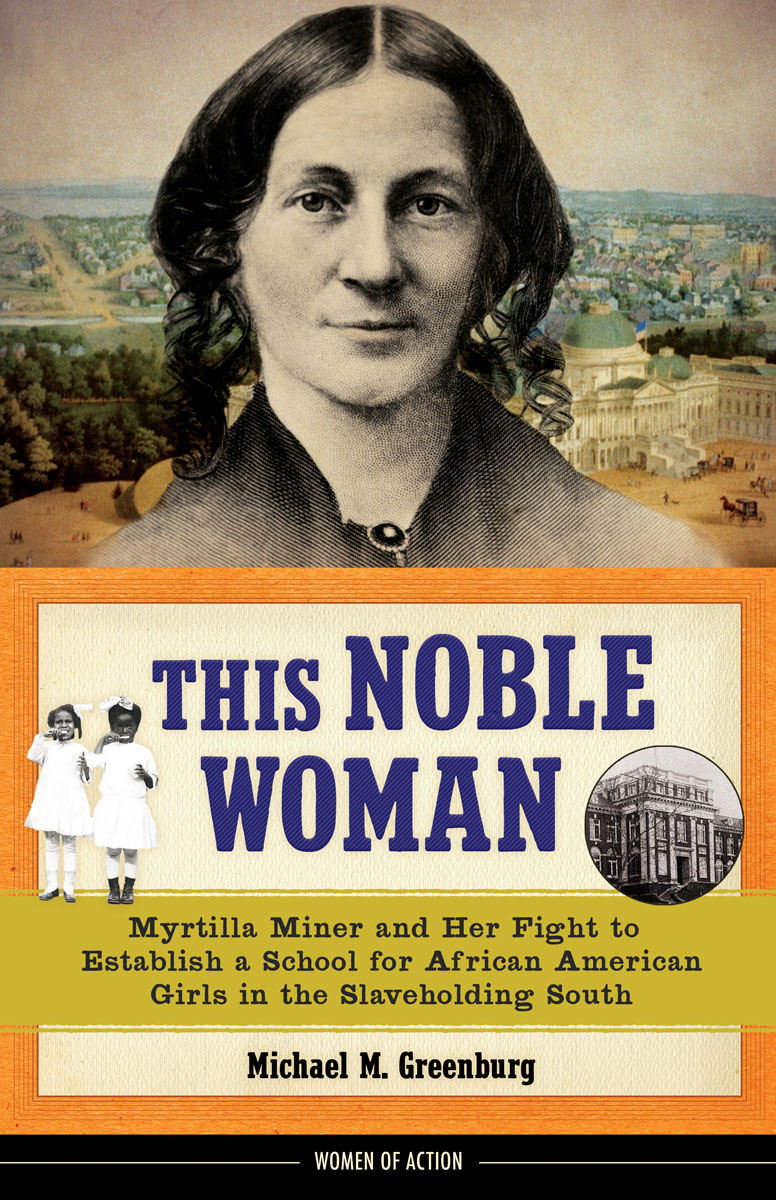

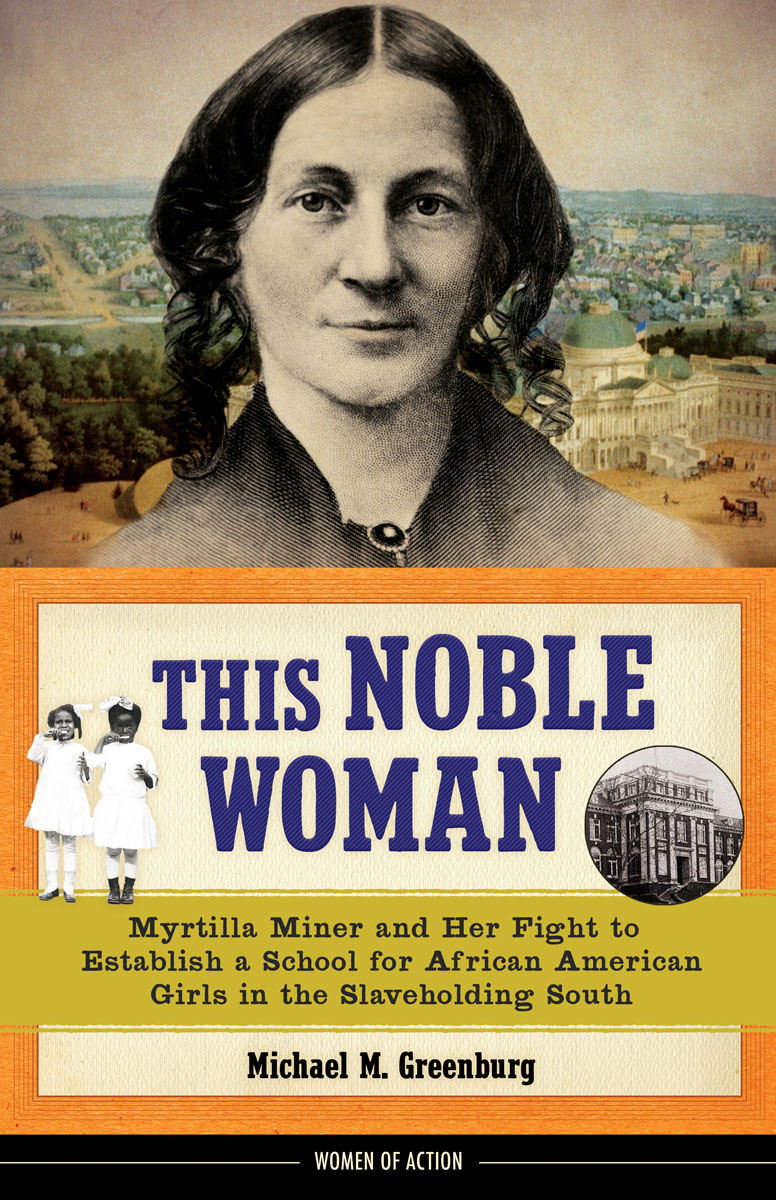

Title: This noble woman : Myrtilla Miner and her fight to establish a school for African American girls in the slaveholding South /Michael M. Greenburg.

Description: Chicago, Illinois : Chicago Review Press Incorporated, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017040095 (print) | LCCN 2017044969 (ebook) | ISBN 9780912777108 (adobe pdf) | ISBN 9780912777122 (epub) | ISBN 9780912777115 ( kindle) | ISBN 9780912777092 (cloth)

Subjects: LCSH: Miner, Myrtilla, 18151864. | Women educatorsUnited StatesBiography. | African AmericansEducationHistory19th century. | Antislavery movementsUnited States.

Classification: LCC LA2317.M524 (ebook) | LCC LA2317.M524 G74 2018 (print) | DDC 371.829/9607309034dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017040095

Interior design: Sarah Olson

Printed in the United States of America

5 4 3 2 1

For my sister, Gail Richardsona lifelong educator

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

TO PRESERVE A MEMORY

T he Gilded Age of railroads and factories swept across America in the mid-1870s. Reconstruction, the process of admitting the Southern states back into the Union after the Civil War, had helped to rebuild a fractured nation, and slavery was but a sad and shameful memory, abolished with the flourish of Abraham Lincolns pen and the blood of many. Myrtilla Miner had been dead since 1864. Her legacy, overshadowed by heroes such as Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman, and William Lloyd Garrison, seemed to fade as the years passed.

A writer and friend of Myrtillas by the name of Ellen OConnorNelly, as she was known to friendswas saddened by the waning memory of Myrtillas work. Ellen knew that the fight to bring justice to African Americans before the Civil War had taken many forms and often extended far beyond the cause of abolition, a movement to end slavery. Myrtilla, the daughter of poor white farmers from Madison County, New York, had done her part to bring human rights and dignity to African Americans through the gift of education. She had traveled to Washington, DC, a hotbed of slavery and racial tension, and bravely opened a school for African American girls. Myrtilla Miner [was] one of the heroines of the irrepressible conflict, wrote US senator Henry Wilson in 1874, not because she figured largely upon the theatre of popular discussion, or entered her public protest against the evils of slavery, but because in the humble walks of the lowly she quietly sought out and with patient and protracted effort educated the children of the proscribed and prostrate race. Senator Wilson viewed Myrtilla as someone who in her own quiet and humble way helped African American childrenand the nation as a wholethrough education.

Ellen OConnor was determined to tell the world about her friends work and decided to write a book about her. I loved her very much, she wrote to Myrtillas brother Isaac in 1886, & felt that the story of her heroic labors here ought to be told.

The famous poet Walt Whitman was a longtime friend of Ellens. He described her as a superb woman, without shams, brags; just a woman. In the early 1850s shed worked as a journalist for the antislavery newspaper The Liberator, as well as with the womens rights journal The Una. Later in life, when asked to defend herself as an equal suffragist, one who supported equal rights for women including the right to vote, Ellen said that she was one at birth and that simple justice required no defense.

She had shared many interests with and known many of the same people as Myrtilla. Through the years Myrtilla had visited Ellen and her husband at their home in Philadelphia and then in Washington, DC, and the two women had developed a close bond. The love & affection which you express for me I fully reciprocate, & then I have a feeling of resting upon you as I have upon no one else, wrote Ellen in an 1861 letter to Myrtilla. I long sometimes for any body to think or act for me, but you are the only one who ever does.

Myrtilla spent the last years of her life in California, returning to Washington, DC, in 1863 only after being gravely injured in a horse and carriage accident. As she lay dying in the Washington home of a mutual friend, it was Ellen who passed hours of each day comforting her, tending to her correspondence, and listening to Myrtillas stories. Inspired by Myrtillas years of struggle to bring education to African Americans, Ellen became personally involved in carrying her friends work forward for future generations. She dedicated herself to Myrtillas cause and in the years following Myrtillas death became a trustee of the Miner Fund, an organization formed to carry on the work of African American education. In this role, Ellen came to know many of Myrtillas friends and former students and learned more and more about her friends life. She was, perhaps, the perfect person to tell Myrtillas story.