First published in 2021

Copyright Matt Chisholm, 2021

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

The images featured in the picture section are from the authors private collection.

Allen & Unwin

Level 2, 10 College Hill, Freemans Bay

Auckland 1011, New Zealand

Phone: (64 9) 377 3800

Email:

Web: www.allenandunwin.co.nz

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065, Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of New Zealand.

ISBN 978 1 98854 753 4

eISBN 978 1 76106 242 1

Design by Kate Barraclough

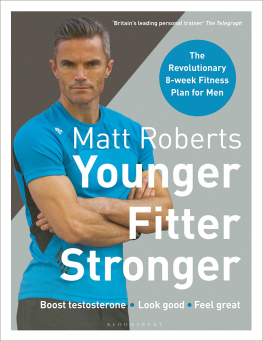

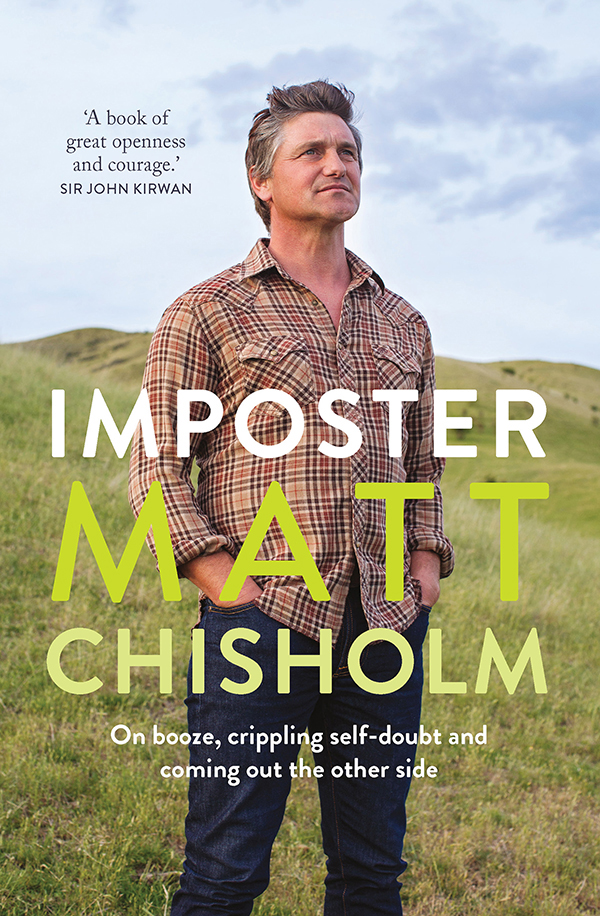

Cover photograph by Lottie Hedley

For my family Elle, Bede and Finn for teaching me so much. I love you.

It was 2018. I was 42 years old and living the dream. A small-town boy from the Deep South who had come good. I had regularly hung out with broadcasting greats Mark Sainsbury, Paul Holmes and Mike Hosking, and had interviewed a heap of New Zealands movers and shakers. I was invited to swanky parties with the whos who from our largest city. I got free tickets to the theatre and comedy festivals. I had two great jobs I was one of only five reporters on Sunday, the only current affairs programme left on New Zealand television, and I was hosting TVNZs biggest reality show, Survivor New Zealand.

Other than a few animals, I had everything Id ever wanted. I had recently married Elle, a smart and beautiful woman who believed in me more than I believed in myself, and together we had two healthy, happy baby boys Bede and Finn. We had just sold a million-dollar home on Aucklands North Shore. We had 33 acres of prime Central Otago dirt, and we still had a heap of dough in the bank. I even drove my dream vehicle, a brand-new Toyota Hilux ute. It was black. It had to be black. We regularly holidayed in the Islands, or visited our own hotspots. I looked fit, healthy and happy, on the face of it at least.

I had been working in prime-time television for a decade. Apparently, I had made a name for myself on Close Up, Seven Sharp and Fair Go for having a great smile and an even better, infectious, laugh. I was the cheeky bloke who got away with asking awkward questions. The bloke with colourful shirts and good hair who was up for anything. I jumped out of buildings, swam with sharks and crawled through caves. If it was going to make good telly, Id do it. I didnt just have a laugh with ordinary Kiwis doing extraordinary things, either. I was equally at home chasing ratbags down the street or giving our marginalised a voice. I told some really personal stories about my big brother Nick, who couldnt walk or talk but still managed to find love.

Whatever I did, I usually looked like I was having fun. My colleague Toni Street certainly thought so. One year, on World Happiness Day, she put together a package with me clowning around and laughing with heaps of my interviewees. She introduced the piece by saying something like, Its World Happiness Day, so take a look at the happiest person on our team, reporter Matt Chisholm.

What Toni, our viewers, and pretty much everyone else didnt know was that, in a way, I was lying to you all. The happiest person on the team had been dreadfully unhappy for a lot of the time he was on television. I had been struggling with alcohol and my mental health for years. I always felt like I didnt belong in a newsroom I felt like a drunken country hick whod got a bit lucky. I felt like it was just a matter of time before Id be found out. I felt like any day soon someone would tap me on the shoulder and tell me Id had an okay innings but my time was up. I think they call it imposter syndrome. Regardless, Im not wired for sitting at a desk, reading and writing. I always felt like I had to work bloody hard just to keep up with my colleagues. Id often go in to work early and head home late. I worked heaps of weekends, just so my work was as good as it could possibly be. I always said yes to work and no to everything else.

After a decade in the game, I was buggered. I might have been invited to parties, but I didnt go to any of them. I had turned into a recluse. If it hadnt been for my wife, and work, I wouldnt have left the house. Hard work was all I knew, and my philosophy wasnt smart. I once told an HR woman, who was looking out for me, Its better to burn out than fade away which was pretty much what happened in the end.

I always knew it would happen. I always knew that there would come a time at TVNZ when I would snap. That time came in December 2018, when I had hit my last deadline for the year. It came when I wasnt doing anything positive for myself, when I wasnt exercising or sleeping. It came when I took sleeping pills before I went to bed every night and aspirin when I got up every morning. It came when I thought Id been treated unfairly, and it came with two smoking barrels. And I reckon those who were in the firing line received the result of 30-odd years of pain and mental anguish. After I fired my shots, I beelined it for home a miserable, dark, dingy rental with few windows and extremely close neighbours. Elle asked if I needed to see the doctor, and for the first time in my life I said yes to that question. Then I went to bed and cried for a few days. I agonised, How the hell am I going to get off this bloody treadmill? I had everything Id ever wanted, but at the same time I was the unhappiest Id ever been. I was broken and I was stuck, and I couldnt see how life would get any better.

I was born in Milton, a small farming and forestry town about half an hour south of Dunedin. If people couldnt afford a house in the southern city, which has always been relatively inexpensive, theyd often move to Milton. They built a prison there back in 2007. I always tell people they should have just put a fence around the town, but thats probably a little unfair. Either way, Miltons unofficial name in the Deep South is Crab Town, which has nothing to do with marine life and everything to do with promiscuity. Milton, or the town of opportunities as its roadside sign suggests, was full of farmers and the people who serviced them shearers, freezing workers, forestry and factory workers. Unless you were one of the few professionals, you either had land and money or you didnt. The Chisholms didnt really fit into any category. We were middle of the road, at least in terms of money. I had a good start in Milton, though, and cried when I left at the age of eleven.

My father, Alan, was born in Dunedin. He was a handsome man who was reasonably smart, though he had two cracks at School Certificate. His father, Malcolm, was a pilot, teacher and musician. His mother, Margaret, an office administrator at Cadburys and at a Dunedin primary school. Dad was going to become either a teacher or a stock agent. Im not sure why he left the city to become the latter and deal with farmers, buying and selling animals. I often wonder how life would have turned out if he had become a teacher instead. I think Dad was good at his job and was respected for it. He worked and played hard away from the house, and was definitely the boss in our male-dominated home (Mum, Dad and four boys). Back in the 1980s and 90s, stock agents spent hours at pubs, socialising and networking with their colleagues and clients. Dad was no different, meaning that my brothers and I became very adept at answering the phone and taking messages for him. I would have been picking up the phone and saying, Good evening, Matt Chisholm speaking. How can I help? regularly by the age of about five.

Next page