A group of fellows at Mayo Clinic, spring 1917. The women, left to right, Dr. Della Drips, Dr. Esther Owens (Ashton), Dr. Leda Stacy, Dr. Winifred Ashby, Dr. Dorothy Pettibone (Bruno), and Dr. Georgine Luden.

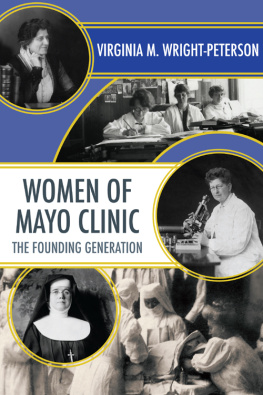

WOMEN OF MAYO CLINIC

THE FOUNDING GENERATION

VIRGINIA M. WRIGHT-PETERSON

Text 2016 by Virginia M. Wright-Peterson. Other materials 2016 by the Minnesota Historical Society. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, write to the Minnesota Historical Society Press, 345 Kellogg Blvd. W., St. Paul, MN 551021906.

www.mnhspress.org

The Minnesota Historical Society Press is a member of the Association of American University Presses.

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481984.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481984.

International Standard Book Number

ISBN: 978-1-68134-000-5 (paper)

ISBN: 978-1-68134-001-2 (e-book)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Wright-Peterson, Virginia M., author.

Title: Women of Mayo Clinic : the founding generation / Virginia M. Wright-Peterson.

Description: St. Paul, MN : Minnesota Historical Society Press, [2016] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015037030 | ISBN 9781681340005 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781681340012 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Women in medicineHistory. | Mayo Clinic.

Classification: LCC R692.W75 2016 | DDC 610.82dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015037030

Front cover images, clockwise from top left: Maud Mellish Wilson, head of publications and library; Eleanora Fry (at left), illustrator; Dr. Georgine Luden, cancer researcher; Alice Magaw and Sister Joseph Dempsey in surgery with Dr. Will Mayo; Sister Joseph, hospital administratorall used by permission of the W. Bruce Fye Center for the History of Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota.

This and other Minnesota Historical Society Press books are available from popular e-book vendors.

DEDICATED TO

Marlys, my mother,

who introduced me to the wonder of stories

AND

Kristina, Harper, and Heath,

who now share the joy of reading with us four generations deep

INTRODUCTION

The idea for this book originated during Womens History Month in 2010, when a few colleagues and I working in the department of education at Mayo Clinic collaborated to create a Jeopardy game based on women from Mayos past. When I visited the Mayo Clinic Historical Suite, I expected to find information on the few women I knew had been a part of the clinics history. Instead, I was astounded to find name after name, folder after folder, and box after box of information on women involved in the very earliest days of the practice. I had never heard of most of these women, although I was born in Rochester and worked at Mayo Clinic for over seventeen years. I learned that several of the first physicians were women, and they started the laboratory, established radium therapy, opened a womens health section, and conducted cancer research. And there was a secretary, along with some Mayo nurses, who deployed with a medical unit to France during World War I. Other women played key roles in establishing the registration and medical records systems.

After the Jeopardy game, I looked at what had already been written about the history of women in southeastern Minnesota, thinking perhaps I had just missed learning about these women somehow. I checked one of the most comprehensiveor so it seemedhistories of the city of Rochester. I did not see much about women in the narrative, so I counted the photographs to estimate what proportion of the book focused on women. The book contains 270 photographs of people. Forty-nine of the images, only 18 percent, are of women. If that is not discouraging enough, I noticed that there are almost as many photographs of horses in the book as there are of women. And if the car had not replaced the horse midway through the narrative, there undoubtedly would have been many more pictures of horses.

At that point, I knew I had to write this book.

I have been on a fascinating four-year journey researching and writing. The stories continue to amaze me, but I encountered obstacles along the way. First, we do not collect womens stories, even unpublished, to the same extent that we retain mens stories. Men have historically been in the public sphere more through their vocations and military service. So they tend to write and be written about more, leaving more of a record. For every womans story featured in this book, there are many, many more women who could have been included, but their names and narratives do not appear, or only minimal facts remain.

My intention is to provide a chronological narrative of Mayo Clinic focused on the most significant contributions of women without unnecessarily duplicating what has already been included in other histories, such as those on the Sisters of Saint Francis and Mayo Clinic nurses. In most cases, the stories and women included are representative of countless other women whose dedication and competence make Mayo Clinic the world-class organization it is. Once the nursing profession was fully integrated into the hospital and clinic practices, women began to account for 60 to 70 percent of the total staff and employees, a gender ratio that continues today.

In addition to a gender bias in recording histories, there is also racial and socioeconomic bias. Most of the characters in this narrative are white, middle-class women. I could find very little on women in lower economic circumstances. Sophia Tandberg Hogenson, the first janitress at Mayo Clinic, is an exception. Thanks to a remote mention in clinic records and information provided by her family, at least a portion of her story is here. But I know there are many, many more women who worked in entry-level jobs, making contributions deserving of recognition, whose stories we have lost. Also, there were very few women of color living and working in Rochester during these years, and I could find very little information about those who did. Again, I am grateful that we have some information on the first Spanish interpreter, Beatriz Montes, who came to Rochester from Havana, Cuba.

Depth, in addition to breadth, was also a challenge. I would have liked to include more of the personal, intimate side of all of these women. I have a sound foundation of dates, places, and actions, which is impressive, but I could not completely identify what motivated and sustained each of them. Relatively few letters and diaries written by these women survived them.

Nonetheless, these are powerful stories of strong, intelligent, and courageous women who persevered at a time when opportunities for women were limited. These women thought big and followed through with their plans despite barriers they encountered.

Quite possibly Mayo Clinic would have been very different if the men, especially Dr. William Worrall Mayo and his sons, had not been willing and wise enough to include capable women in their practice and in their personal lives. They were inclusive when it came to gender and religion. Perhaps these stories will help provide a more complete picture of the founding years.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481984.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481984.