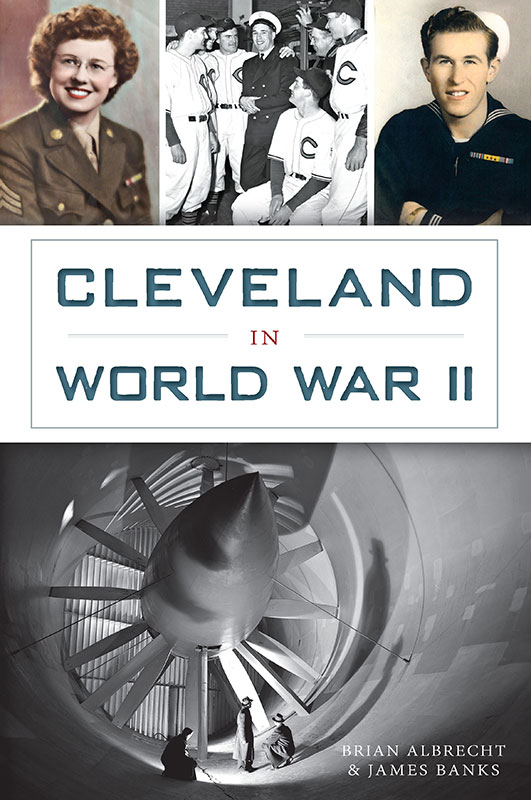

Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2015 by Brian Albrecht and James Banks

All rights reserved

First published 2015

e-book edition 2015

ISBN 978.1.62585.412.4

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015947684

print edition ISBN 978.1.62619.882.1

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the authors or The History Press. The authors and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This book was the result of a referral from John Grabowski, a vice-president of the Western Reserve Historical Society and associate professor of history at Case Western Reserve University. The authors are indebted to him for his endorsement.

The History Press had contacted him regarding his interest in writing a book on the history of Cleveland during World War II. He referred the project to the Crile Archives Center for History Education.

James Banks, founder/director of the Crile Archives, thought the proposed book merited some consideration but could be improved if it included Brian Albrecht, a Plain Dealer reporter. The authors combined experience of more than fifty years of writing, research, teaching and production of documentaries and public programming provided a rich reservoir of material.

The Western Reserve Historical Library recorded interviews for its exhibit on World War II Up Close and Personal. The exhibit and interviews regarding Clevelanders during the war were keyed to the 2007 PBS series The War, directed by Ken Burns. Under the leadership of Edward Pershey, access was acquired to the digital and photo collection in that project. Thanks is hereby given for their splendid assistance.

The photograph collection of the Cleveland Press at Cleveland State Universitys Michael Schwartz Library provided many of the images used in this work. Thank you to William Barrow and his staff at the university. Additional thanks go to the Cleveland Memory Project, also at Cleveland State University, as well as Cleveland Historical, a website associated with the CSU library.

Also, the Cleveland Public Librarys photo collection was helpful in completing this work.

At Cuyahoga Community College (Tri-C), we are fortunate to have Jennifer Pflaum as the archivist of the Crile Archives. She has digitized a substantial part of the collection, making it available online at www.tri-c.edu/crile-archive/index.html.

The Western Campus Learning Commons and the Technology Learning Centerled by Michael Collura, assistant dean, and his professional staffhas assisted the authors. We thank them all.

Of particular help was a research assistant, Professor Thomas Lyon of the colleges Western Campus History Department. Also, local historian Ken Lavelles early work on the Crile Hospital was very helpful.

The Maltz Museum of Jewish Heritage, the USS Cod Submarine Memorial and the International Womens Air & Space Museum also provided assistance.

Special thanks to Gretchen Albrecht for digital image screening.

INTRODUCTION

The damn Japs, the damn Japs bombed Pearl Harbor! Thats how Robert Laczko remembered his birthday party on Sunday, December 7, 1941, when interviewed by a Plain Dealer reporter in 2014.

He was not yet of school age, getting ready for his birthday at his grandmothers house on Buckeye Road. The adults were listening to the old Philco radio when he heard men hollering and slapping the radio and pounding on it.

The excitement was a mix of English and Hungarian, as he recalled. Few knew where Pearl Harbor was. He remembered his mother crying. Soon, all the women in the home were crying, he said.

It was a day he will never forget.

As the war progressed, he remembered that all the women in his close-knit neighborhood consoled neighbors who lost a relative in the war, always with ample food.

He remembered one time, a Dodge OD (olive drab) army staff car came to a neighbors house, and some officers got out. He didnt know what it was about. Later, he found out that somebody died.

The two ethnic communities of young Laczkos neighborhood, Hungarian and Italian, united when an Italian mother lost two sons, leaving her alone. He remembered, I watched the ladies of our neighborhood take this Italian woman under their wing. It was a beautiful thing, part of the greatest generation.

Beyond the neighborhoods and out to the far Pacific naval base of Hawaii, word of the shocking attack by the Japanese resonated with devastating impact, hitting Cleveland with personal poignancy. Two sons of the city died on the USS Arizona. Rear Admiral Isaac Kidd, fleet commander, died on his flagship, along with more than 1,100 crew members, including twenty-six-year-old ensign William Halloran. Both died instantly, incinerated in the blast. Weeks later, when divers searched the sunken wreckage, the only trace of the admiral was his Naval Academy ring, class of 1906, fused to a stanchion.

Kidd was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor posthumously for conspicuous devotion to duty, extraordinary courage, and complete disregard of his own life. He was known as a working admiral. His wife, Inez, christened the DD-661 USS Kidd, a destroyer serving in the Pacific, a year after she lost her husband.

A native of Cleveland, Kidd was born on March 26, 1884, and graduated from West High School. His son, Isaac Kidd Jr., graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy six months after his fathers tragic death. Ike, as he was known, served in the Pacific in World War II, retiring as an admiral after nearly half a century of service.

The sudden and devastating loss of three thousand lives on American soil struck most Americans in waves of numbing disbelief. We were neutral, but our unguarded shores and far-flung islands were under attack. The shocking but irrelevant phases of months ago, like the rape of Nanking or the Battle of Britain, became instantly real as Remember Pearl Harbor joined the chorus of the Allies cries.

The many neutrality acts of the late 1930s and President Franklin Roosevelts rhetorical attempt to quarantine the aggressor fell on diffident ears in Congress. The nation was still economically weary and globally disengaged. The lingering disillusionment stemming from the Great War and the priority of finding a steady job were far more important than Europes perennial troubles. Clevelands large ethnic populations were more firmly planted in the United States than in the old country.

The news out of Europe in 1940 was not good. The desperate evacuation at Dunkirk and the photos of Hitler in Paris, while disturbing, did not concern isolationist Americans. The establishment of a peacetime draft in 1940, the first since the Civil War, did become law but was opposed by Clevelands two congressional representatives, Democrat Martin L. Sweeney and Republican Frances Payne Bolton, the first female from Ohio to hold a House seat.

The president had concluded an executive agreement with Great Britain to exchange fifty aged destroyers for islands in the Caribbean, prompting Congresswoman Bolton to remark that if he can do what he likes with our destroyers without consulting CongressGod alone knows what he will do with our boys.

Next page