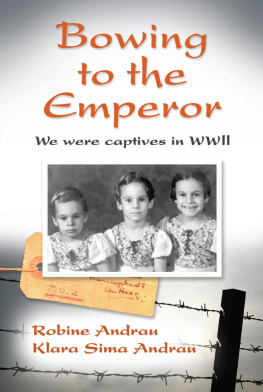

Robine Andrau - Bowing to the Emperor: We Were Captives in WWII

Here you can read online Robine Andrau - Bowing to the Emperor: We Were Captives in WWII full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2015, publisher: BookBaby, genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Bowing to the Emperor: We Were Captives in WWII

- Author:

- Publisher:BookBaby

- Genre:

- Year:2015

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

Bowing to the Emperor: We Were Captives in WWII: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Bowing to the Emperor: We Were Captives in WWII" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

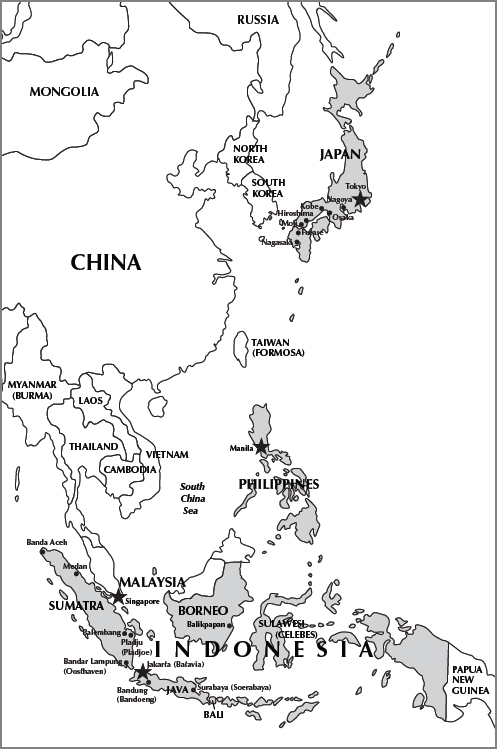

More than 10,000 women and children. Thats how many civilian prisoners of the Japanese were packed into Tjideng, reportedly the worst Japanese concentration camp in Java during World War II. Among these 10,000 mostly Dutch women and children were Hungarian-born Klara and her three young daughters. Meanwhile Klaras Dutch husband, Wim, a captain in the Royal Dutch Air Force, was among the 1500 military men crammed into a hell ship and transported to Japan as a slave laborer.

Bowing to the Emperor: We Were Captives in WWII, a memoir/biography penned by Klara and daughter Robine, chronicles the Andrau familys experience during those dark years in the then-Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia) and in Japan. The story reveals the fierce determination and ingenuity of a mother and the strength and leadership of a father when faced with starvation, brutality, and unspeakable living conditions.

Klaras part of the story details what she did to keep the couples three children and herself alive and well in body and mind, both during the Japanese occupation in 1942 and during the childrens and her subsequent internment. Left with no income after Wim was taken away, Klara scraped along by giving language lessons, teaching the three Rs to classes of children, and making and selling jams.

Later, when interned in camp, she supplemented their daily diet of a handful of rice, a little piece of gummy bread, and a few leaves of a spinach-like plant by digging up the packed earth and planting some leafy vegetables, which she fertilized with night soil. She also pawed through the camp kitchen garbage looking for anything edible and knit socks for the Japanese to earn some sweets for her children. She kept the wonder of Christmas alive one year by stealthily evading the patrolling Japanese guard in the predawn darkness, climbing a fir tree next to the barbed wire and bamboo camp fence, and sawing off the trees top with a toy saw. When decorated with a few candles, the top was transformed into the most magical of Christmas trees.

Wims story centers on his role as the senior officer in charge of 400 Dutch and later an additional 200 American and 2 British POWs in camp Fukuoka #7 in the Japanese coal-mining town of Futase. He led his men with good humor and optimism and negotiated tirelessly with the Japanese commander, sometimes successfully, for shorter work hours in the coal mines (from 12-to-14-hour days to 10-to-12-hour days), for more rest and recreation time (from a partial to a full day off every ten days), and for more food.

Beatings on the part of the Japanese guards were a perennial problem. By bypassing the Japanese commander and slipping a list of brutality complaints among other suggestions for changes into the hands of the visiting Swedish consul, Wim succeeded in marginally improving the situation for his men. His greatest success, however, was in maintaining order and discipline among the prisoners, reducing friction and increasing understanding between the two main national groups, and building morale despite the dirt, near-starvation rations, disease, brutality, and horrendous work and living conditions in the damp dangerous coal mines and the flea- and lice-infested barracks.

Besides being the personal story of a family, Bowing to the Emperor is also a universal story of survival and of hope despite loss of country and loss of all material possessions.

Robine Andrau: author's other books

Who wrote Bowing to the Emperor: We Were Captives in WWII? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.