Aunque seas muy grande y rico, necesitas del pobre y chico.

Though you may be wealthy and tall, you will still need the poor and the small.

Chapter One

Al que madruga, Dios lo ayuda.

God helps the early riser.

(One of Aps favorite dichos)

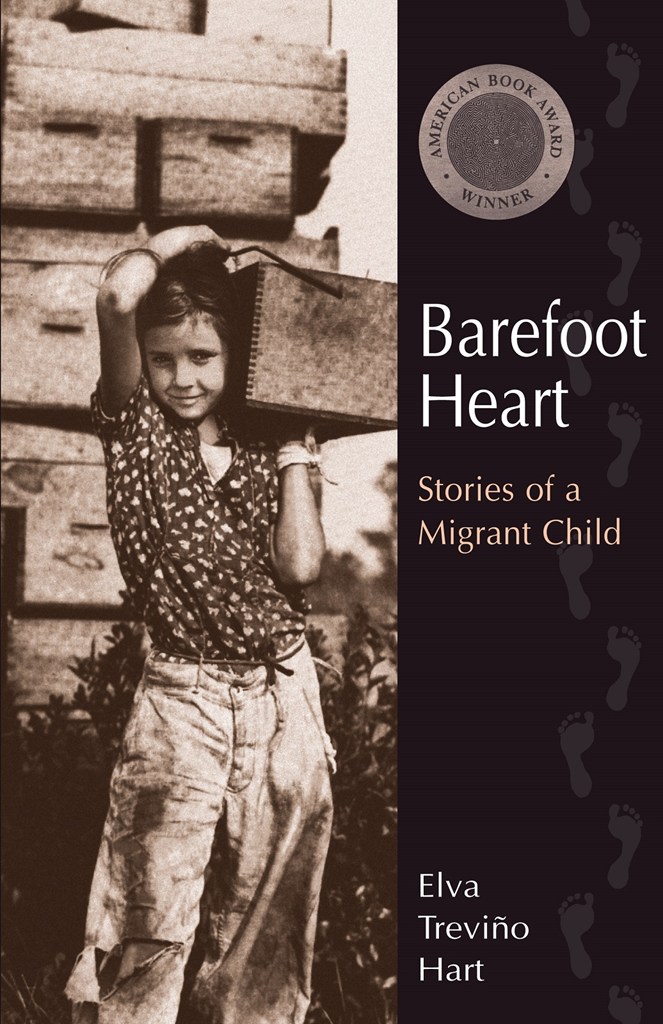

M y whole childhood, I never had a bed. In the one-bedroom rancho where I was born, my ap suspended a wooden box from the exposed rafters in the ceiling. My am made a blanket nest for me in the box. It hung free in the air over my parents bed, within reach of both. If I cried, they would swing the box.

We moved to To Alfredos house in town two years later when Ap left his job as a sharecropper on the McKinley farm. To invited us to come and live with him right after he built the house on my grandmothers property. So my parents, my five older siblings, and I settled into the two-bedroom house with my uncle. My brother Rudy and I shared a room with my parents. I slept on a little pallet on the floor, sort of in the hall that connected the two bedrooms, but still close to my parents bed. They had a double bed and Rudy had a cot. My three sisters, Delia, Delmira, and Diamantina, slept in the other bedroom. To Alfredo and my brother Luis had beds in what would one day be the living room.

When the lights got turned off at night, it was such a small house that we could all hear each other saying good night.

Hasta maana, Ap.

If God wills it, mija.

Hasta maana, Am.

Si Dios quiere.

We went around this way until we connected and were reassured our family was all right. Close and sweet and loving. Lucky me on my small pallet on the floor.

There was a bathroom in the house, but it had no plumbing or fixtures, so we used it as a closet. The outhouse was behind the dirt floor shack in the back yard that used to be my grandmothers house when she was still alive. My mother still scrupulously swept the dirt floor to leave it hard packed and neat in memory of her mother, who used to cook, iron, and sleep in that room.

In the back yard a huge mulberry tree dropped purple stains on the dirt below. In the front a Chinese loquat made juicy yellow plums. These were our growing-up fruits along with the red pomegranate jewels that grew in my Ta Ninas yard. Occasionally, a round cactus that Ta Nina had in her front yard sprouted pichilinges, tiny red fruits the size of a raisin. The taste was so distinctive and the fruit so rare that my siblings and I fought over who got the next one.

To Alfredos house was situated directly between two cantinas. Excitement on either side of us: the click of the billiard balls, the throaty, smoke-filled laugh of the cantineras, and the occasional drunken brawl. Am made me come in the house when a fight started. The music of my nursery days started just before the coming of night like an invocation. I sang Gabino Barrera, El Gaviln Pollero, and Volver, Volver, Volver along with the borrachos and the jukebox. Amalia Mendoza filled our back yard with Spanish, the trumpets and violins in the background.

In the spring of 1953 Ap interrupted our family life at To Alfredos to take us to work in the beet fields of Minnesota. Since we had no car, we went in a troca encamisada with another family. The back of this huge truck was covered with dark red canvas. It looked like a tent sitting on the flatbed, except the sides were reinforced with wood. The man who owned the truck was nicknamed El Indio because his skin, like that of an Indian, was the same color as the canvas, a dark, strong red. I thought he must be very rich to own a huge truck like that. We, on the other hand, owned no car, no house, almost nothing.

He was rich in strong, hefty children, too. Three of them looked like him, with dark red skin and big, stocky bodies. The other two looked like their mother, La Gera, with light, cream-colored skin, but still big and strong. One girl was my age and all the rest were older.

It was still dark when the truck arrived and parked under the light of the street lamp. El Indio didnt have to honk because my father had been pacing by the fence next to the street, waiting and calling out orders to everyone else.