CONTENTS

Amy Rigg, Emily Locke, Kerry Green and The History Press for all their help; Austin Mitchell for all his help; the late Dolly Hardy who did a lot of hard work to get fishermen compensation; Eric Fearnely, Photographers, Grimsby; Grimsby Central Library; Grimsby Heritage Centre; Innes Photographers, Hessle Road, Hull; Jamie Macaskill, Hull Daily Mail; Janeen Willis & Fred Goodman, photographic collection; Jim Porter, administrator at Fleetwood-Trawlers.info; Lyne Asgha, Fleetwood Museum; Mary Houghton for The Last Voyage by her father in chapter 12; excellent photographs from Memory Lane, 528 Hessle Road, Hull; Michelle Lalor at the Grimsby Telegraph; my daughter Alison for all her help on the computer; Steve Farrow for the use of his wonderful paintings; Susan Capes at the Hull Museum & Art Gallery; the US Coastguard; William H. Ewen, Steamship Historical Society of America.

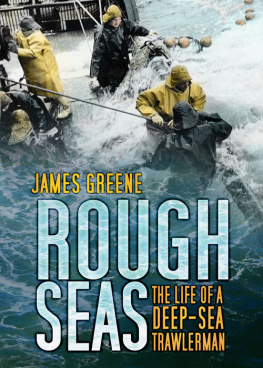

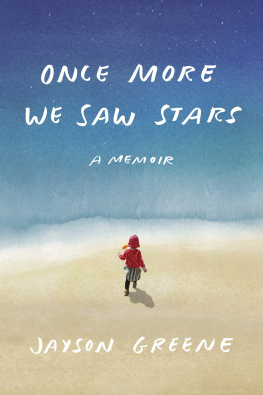

I am delighted to welcome Jim Greenes excellent autobiography because its not only his own life story, but a marvellous insight into the industry in which he served. We wont see the like of either again so its good that Jim has not only told the tale of fishermen like him who spent most of their lives in peril on the sea, but gives us a fascinating picture of the rise and fall of our once great fishing industry. Fishing shaped the lives and built the fortunes of the three great English fishing ports of Grimsby, Fleetwood and Hull, but was almost totally destroyed by the world trend to 200-mile limits and by our own inability to rebuild fishing in our own rich waters thanks to a Common Fisheries Policy which gave equal access to a common resource, meaning that our rich fishing grounds were open to the French, the Dutch, the Danes, and others all managed not by us for our purposes but by the European Commission doling out paper fish in political decisions taken in Brussels.

Jims life brings home the drama, the dangers, the highs and the lows of the lives of the thousands of fishermen who toiled in our distant water fishing industry up to the time when it suddenly found itself with nowhere to fish, and that story deserves to be told and remembered before the last generation of distant water fishermen fades into history, as most of their industry has already done. In Jims day Grimsby boasted of being the Worlds Premier Fishing Port, a title disputed by Hull but rightfully ours because, though Hull caught more fish and regularly won the annual Silver Cod award, Grimsby caught quality rather than quantity and had a bigger and more diversified fleet fishing middle and near waters as well as Iceland, Greenland, the Faroes, Norway and even Canada.

So Jim is describing not just an industry, which was very profitable for the men and even more so for the big powerful owners who ran it, but a way of life unique to the three ports where fishermen lived in tight fishing communities of terraced housing clustered round the docks, sons followed fathers, as Jim did his, and wives raised the families while absentee fathers fished for three weeks away, then home for perhaps three days.

The men faced the restless waves and the distant waters but spent much of their time when ashore in the rough, tough world Down Dock from which men, money and life spilled out into the surrounding streets, particularly in Freeman Street, Grimsby, with its pubs, shops, markets, training facilities and schools. Down Dock was the focus of fishing life and an almost tribal existence. The offices, the engineering, provisioning, landing marketing and auctioning of the fish all carried on there and the merchants and owners premises clustered round the market from which the precious fish were despatched by rail, up to Dr Beechings railway cuts, then by road out to the waiting world.

Down Dock was a tough, male, insular world somewhat separated from the rest of Grimsby, as was Hessle Road in Hull and the fishing streets of Fleetwood. Fishing made the towns rich but in return the respectable burghers looked down, almost askance, at the industry and the men whod generated the wealth of their towns. Down Dock was another world, one where fishermen worked, lived and strutted the nearby streets like kings, even though, in fact, they were lashed to their industry like seaborne serfs by the powerful cartel of fishing vessel owners whose word was law.

Its good and right that that way of life should be written up for history and Jim Greene has done a marvellous job in recreating the industry by telling his own life story simply and honestly and without pretension or stylistic tricks for the future generations wholl never see its like again. With all its toughness, tragedies and terrors in distant waters our big, English fishing industry has gone, leaving perhaps a score of middle water vessels in Grimsby, a few freezers in Hull and a small remnant, some Spanish owned, in Fleetwood. The fishing communities have been broken up, their continuities and lifestyle destroyed. Believe it or not, its now difficult to recruit fishermen in the old ports because so few youngsters want to go into an industry to which most once flocked. Jim never wanted his own son to go into the industry to which hed devoted his own life.

The death of fishing was sad, even shocking, because a once powerful industry was scuttled. Its vessels were sold off, sent to Spain, Africa or anywhere which could pay, or scrapped. Its owners, well compensated by the government, put the money in their pockets and scattered, leaving the towns that had made them and taking their money with them. The men were thrown onto the scrapheap with neither compensation nor redundancy because these slaves of the sea were viewed as casual. Neither was paid until a tribunal case in 1994 proved that fishermen were in fact employed, not the casual workers this almost captive workforce had (unbelievably) been seen as in 1976. Then only thirty years after the death of the industry and after a long struggle by the British Fishermens Association, by Dolly Hardie and by the port MPs, the Labour Government paid compensation for the loss of jobs and livelihood, a compensation which is only now being grudgingly and unfairly finalised. No other group of workers had such a hard, dangerous life. None has been as badly treated.

There is no point in me telling that part of the story over again. Jim Greene tells the whole story brilliantly in his own words through the narrative of his life, starting in Fleetwood, moving upmarket to Grimsby, fishing first as deckie learner, then mate and finally skipper. He was one of the youngest, too, but thank heavens his tough life has been remembered and preserved forever as it deserves to be. Enjoy.

Austin Mitchell

MP for Grimsby

CHAPTER 1

It was a cold, stormy night in March 1938, the month and year I was born. Somewhere off the west coast of Scotland the Fleetwood coal-fired steam trawler Hayburn Wyke was dodging, her bow ploughing into the teeth of a storm. Fishing operations had been suspended due to the bad weather. All crew were sleeping except for two men on watch in the wheelhouse and the chief engineer and his firemen working hard to shovel coal into the furnaces to keep fires going and the engine running smoothly.

In the wheelhouse the watch kept a sharp lookout for other ships while the bosun studied the weather. An ice cold wind whistled through the wheelhouse, in darkness except for a small light that lit the compass. The only other light came from the depth sounder flashing at regular intervals. It was noisy; the windows rattled in the gale and the ship was constantly battered by heavy spray. The wind ripped through the rigging, howling like some tortured creature lost in the night.