Contents

To Patty, Celia, and Henry

PREFACE

In the Age of Progress, Problem

CHRISTMAS 1924

SPRINGFIELD, MASSACHUSETTS

I N THE MID-1920S THE WORLD as many had known it was coming to an end. The Crash was around the corner. In the already slumping western Massachusetts working-class cities of Springfield and Worcester, two older men took an accounting. One white, the other black. One utterly obscure, one only recently forgotten.

Louis Birdie Munger was a doer, a thinker, and an extraordinary (if unheralded) inventor. He wasnt a man of reflection, but when he answered the knock at his door in Springfield and signed for the express package something clicked. It wasnt what was insidea holiday gift from relativesbut the post date on the outside. It had left the Pacific Coast only twenty-six hours earlier, an astonishingly brief span of time. An old, pulse-quickening sensation stirred. His mind raced.

In a subsequent article in the local newspaper, Munger colorfully described a time few remembered. Two photographs accompanying the story seemed to say it all. Both were of him on bicycles. But in one, the earlier one, Munger had short hair, a tidy moustache, and a dark dress suit. He was sitting stiffly upright, formal, gentlemanly. The bicycle was a fashion accessory, like the fluffed silk handkerchief in his lapel pocket. In the companion shot, taken only a few years later, he was wearing a sleeveless T-shirt and tight shorts, and sported a waxed handlebar moustache stretching to the east-west cardinal points. He was hunched over, streamlined, racing. The look on his face was narrow and competitive.

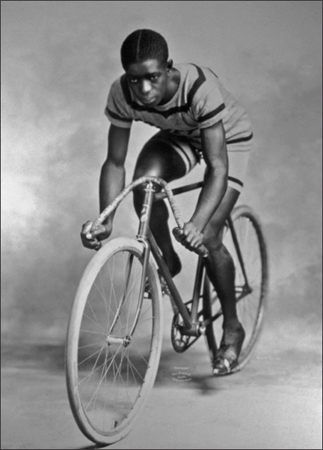

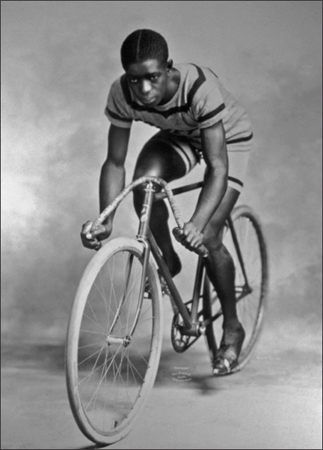

The sport of that moment was bicycle racing, and for a decade, from the mid-1890s to the early 1900s, it was all anybody wanted to talk about. Hundreds of professional racersbeautiful, virile gods of sportcompeted before millions of spectators at tour stops in San Francisco, Chicago, New York, and dozens of other cities where they were received like heroes, with parades, newly built and record-fast oval tracks, and fan pins and cigarette packs adorned with their handsome images. Scientists were transfixed as the racers hurled themselves against the unknown of terrestrial velocity; they wielded tape measures and calipers to unravel their physiology in the hope of explaining the speeds they attained, but in the end they, too, were stumped and merely hailed the scorcher as a new exquisite athletic form, like an evolved species descended from a future world.

Nameshot, fast bicycle nameswashed across Mungers mind as if it were yesterday: the Orient, the Yellow Fellow, and his own Birdie Special. He didnt say it, but his bike was the watch charm, the sleekest, most radically designed, most pilot-adored racing bicycle in the world. If you were lucky enough to own a Munger, your intention was plain: you wished to be the fastest thing in existence. He was sought out by the most cyclonic men on the planet to break records, eclipse thoroughbreds, even catch speeding locomotives.

Maybe as much as the time-bending express package, what helped prompt all of thisthe interview, the recollections of his time and place in the era, the sifting through scrapbooks for race photographswas a recent visit (and, as it turned out, the last visit) from his now graying protg Marshall Taylor. The colored whirlwind had begun his own autobiographical project, he told Munger, spending the last several years getting down on paper what he and others could remember before it was too late.

Munger couldnt recall when he initially met Taylor, but he never forgot his first day with him at the track. When he stopped his timepiece after the youngsters mile-long sprint, he shook his head in amazement: 2 minutes and 7/100ths of a second. The world record was just two-hundredths of a second faster. At the time Taylor was sixteen, self-taught, and working as an errand boy at an Indianapolis bicycle shop. The old racer in Munger felt something that transcended envy; he felt the goose bumps, the breathless joy of discovery that comes from seeing someone do what you love better than anyone you ever dreamed could do.

At Mungers urging, Taylor had traveled the country, then across the Atlantic, and finally from one end of the earth to the other to compete against the reigning champions of England, Germany, France, Italy, and Australia. Speed was the currency of the moment, and the man, country, and race who could claim to be its master was worth something incalculable. The obstacles abroad were considerable: rugged overland rail travel, transoceanic steamers, and the vast distances that separated home and away.

At home, it was bleak. In 1899, at the outset of Taylors assault on the record books, a total of 400 black people were lynched in Georgia, Mississippi, and a half dozen other states, the most of any year in U.S. history. It was not a good time to be visible, much less the most prominent and prominently victorious black man in America. On banked outdoor tracks Taylor tucked in behind noisy, steam-belching, rubber-burning, crash-prone motorcycles and raced furiously against the clock to see what was possiblea mile a minute? Faster?but he also raced against flesh-and-blood rivals, wheel to wheel, elbow to elbow, skin to skin. In one of his first professional races, he effortlessly accelerated past a struggling veteran, exhorting as he passed him, That was too easy!

His victories, and the sensational, crowd-pleasing way in which he won, led to threats, assaults, and the open collusion of his main American race circuit rivals to defeat him. The popular sporting press didnt know what to make of himhe didnt drink alcohol or smoke tobacco, and he stubbornly refused to race on the Sabbath, either for world championship titles or $10,000 race purses. But I never heard before of an athlete who had conscientious scruples, and no one believes you, Major, a newspaperman protested. Another writer ridiculed him as a Christian Narcissus who feels the finger of God whirling his pedals round.

In the end there was only one man the competitive equal of Taylor. His name was Floyd McFarland, also an American and of identical age. He came from Californiaa place where the sheer physical distance to the eastern sporting metropolis had once been insurmountable. He was everything Taylor wasntgarrulous, school-educated, and white. His father was a well-to-do auctioneer; Taylors was a poor servant coachman. The McFarland family was storied, a fabled Virginia clan that settled on land where an immense reservoir of oil and natural gas gushed just beneath the tilled surface. Taylors family was anonymous, neither written about nor recorded as slaves in prewar Kentucky.

They sparred for almost ten years, during which the sport riveted the publics attention the way modern-day NASCAR does. Each became wealthy, made almost daily headlines, and enjoyed unprecedented celebrity as a sportsman, but it was almost as if both feared the lethal consequences of a true championship meeting, of a black striver in the same hot, tight arena with a white master. It was only at the endof the sport, of the boom, and of the erathat their rivalry finally achieved full form. They took passage for Australia, a seemingly neutral venue halfway around the world and yet a place a local legislator called the last part of the world in which the higher races can live and increase freely for the benefit of higher civilization.

Next page