ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank everyone at Bloomsbury, particularly Bill Swainson, the senior commissioning editor, for his belief in the project and his unwavering encouragement. I am also grateful to Nick Humphrey, who is always thoughtful and encouraging, and Anna Simpson for her editorial advice and support as well as Richard Collins for his excellent copyediting. I would also like to thank Anya Rosenberg, Colin Midson, David Mann, Ruth Logan, Penelope Beech, Lisa Fiske and Polly Napper, all of whom have worked hard to produce and market this book.

I should like to thank Rosanna Wilkinson, research assistant at the Imperial War Museum Photograph Archive for her generous help and the Imperial War Museum for permission to reproduce a number of images from their library.

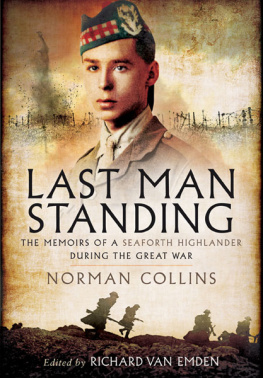

Thank you to my good friends Jeremy Banning, who originally brought my attention to the diaries, and Peter Barton who originally discovered their importance. As always, I am grateful to Taff Gillingham for his help and expert knowledge of the Great War, and to my superb agent, Jane Turnbull, for her continued enthusiasm and encouragement throughout this project.

Thank you, as always, to my wife, Anna, for all her understanding as I disappear to my study to write. A special thank you to my mother, Joan van Emden, whose unstinting support and expert advice is always more appreciated than I can say.

I should also like to thank Peter Martin for the private family photographs he kindly supplied for the plate section as well as for his first hand memories of his father that proved so useful during the writing of the introduction. I am also very grateful to Laurence Martin for his unfailing help and encouragement as I edited his grandfathers memoirs.

Acknowledgement from the Martin family:

Jack Martins family would like to thank Peter Barton for being the first historian to discover this material and confirm its quality to the family.

Their thanks in equal measure also go to Richard van Emden for having such faith in Jacks narrative and making it a book.

A NOTE ON THE AUTHOR

Richard van Emden has interviewed more than veterans of the Great War and has worked on more than a dozen television programmes, including Prisoners of the Kaiser , Veterans , Britains Last Tommies , the award-winning Roses of No Mans Land and Britains Boy Soldiers . His many books include The Trench and The Last Fighting Tommy (both top ten bestsellers), The Soldiers War , Boy Soldiers of the Great War and Prisoners of the Kaiser .

1916

Sunday 17.9.16

Left Hitchin just before 9 a.m. Saw Elsie at her window as we marched to the station. Embarked at Southampton at 4 p.m.

18.9.16

Disembarked at Rouen about a.m. Marched past numbers of German prisoners working in the streets, to a barbed-wire compound where we got some breakfast at a YMCA hut. Crowded with men either going up to or coming down from the line. Played a number of ragtime choruses on the piano. Later I was fetched to play hymns for a service. The chaplain me gave a Testament that I retained until sent home for demobilisation. Medical exam and then entrained.

19.9.16

Arrived at Abbeville after a most uncomfortable journey (thirty-six in a truck) early in the morning. Marched to the Signal Depot where we caught up some of the men who had left Hitchin a few days before we did.

20.9.1622.9.16

Did not have much to do at Abbeville and each evening we were allowed out. Could not go in the Cathedral but saw the massive doors which are its pride. Dont think much of the city some parts are very low, and probably the present circumstances of being a military centre have dragged it lower.

23.9.16

This morning my name appeared on orders to proceed to the 41st Division. I leave tonight and anticipate finding myself on the Somme tomorrow.

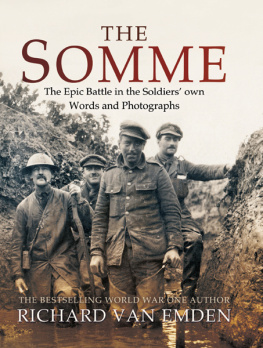

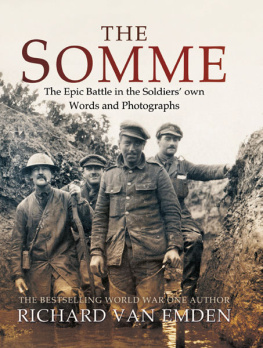

The Battle of the Somme was a campaign essentially conceived out of political necessity. The idea was to show that the British and French could not only launch a successful campaign together but that they could fight alongside one another in a show of military solidarity. That was the primary reason why, in late 1915, the gently rolling chalk downland of the Somme region was chosen as the best place to force a decision on the Western Front in 1916. Hitherto, the area had been little more than a Franco-German backwater where little actual fighting had taken place.

The British had arrived in the summer of 1915, not necessarily to fight in the region but rather to take over more of the front line that stretched all the way from the Belgian coast to the Swiss Alps. The French had been holding by far the greater proportion and as the number of British troops serving overseas grew exponentially in the spring and summer of 1915, so it was felt appropriate that Britain should shoulder a greater responsibility not just in terms of fighting but simply holding the line. Only after the British had arrived on the Somme did the idea of a joint offensive begin to germinate. In February 1916 the Germans attacked the French at Verdun and, as more and more French servicemen were drawn into the fighting further south, so their commitment to a Somme offensive was much curtailed. Indeed, such was the ferocity of the fighting at Verdun that the British were increasingly urged, then implored, to fight at the earliest possible moment so as to draw off German forces from the beleaguered town. The British would put an enormous effort into what optimistically became known as the Big Push. A huge preliminary bombardment followed by a heavy infantry assault would, over days and then weeks, throw back the Germans across French-held territory. The outcome, as it was sold to the British public, was that this was an offensive that might end the war.

Reality was rarely the equal of expectation in the Great War and a catastrophic failure on the first day of the battle was only partially redeemed by limited success in the weeks and months that followed. Success would soon be measured in hundreds of yards rather than in dozens of miles, as each wood, each village and each roadway was contested by British troops determined to take the land in equal proportion to the Germans desire not to relinquish it.

In September 1916 the British introduced a new secret weapon, the tank. This seemed to hold out the prospect of renewed success, but although the Germans were taken by surprise at its appearance, once again the battle stalled. It was just days after the advent of the tank that Jack Martin arrived in France, to be quickly sent forward to join his unit in the line. As a signaller with the 41st Division, a unit used in some of the tanks first assaults, he would quickly get to see all the horror of modern warfare and the skeletal debris of both man and knocked-out tank close to the front line.

24.9.16

Travelling. We left Abbeville in the usual crowded cattle trucks at 9.30 last night. In the morning we were near Amiens. Progress is frightfully slow. Sometimes there were as many as five trains all crawling close behind each other. There may have been more round the bends. Every time we stopped near any orchards some of the fellows would jump out and fetch apples. Two or three got left behind just as we entered the tunnel before Amiens but they walked over the top and caught us up at the other end. Stace, another fellow named Morgan, and I were booked for the 41st Division. We were told to get out at Edge Hill which is the railhead. We found a Middlesex guide who said he would take us to our Division. He walked us right up to Fricourt where we saw the big guns in action for the first time, but after tramping about for some time without finding any trace of the Div. we decided to pad it back to Edge Hill jumped a lorry part of the way. Some cooks at Edge Hill gave us tea and we learnt from a motorcyclist that the 41st Div. was at Ribemont, a few km further back. We jumped a train but it only took us a few yards. After waiting hour we decided to walk to Mericourt where the RTO [Railway Transport Officer] put us into a Rest Camp and promised us some breakfast.

Next page