LIVING OUT

Gay and Lesbian Autobiographies

David Bergman, Joan Larkin, and Raphael Kadushin

FOUNDING EDITORS

Publication of this book has been made possible, in part, through support from the Brittingham Trust.

The University of Wisconsin Press

1930 Monroe Street, 3rd Floor

Madison, Wisconsin 53711-2059

uwpress.wisc.edu

3 Henrietta Street, Covent Garden

London WCE 8LU, United Kingdom

eurospanbookstore.com

Copyright 2018

The Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System

All rights reserved. Except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical articles and reviews, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, transmitted in any format or by any meansdigital, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwiseor conveyed via the Internet or a website without written permission of the University of Wisconsin Press. Rights inquiries should be directed to .

Printed in the United States of America

This book may be available in a digital edition.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Gonzlez, Rigoberto, author.

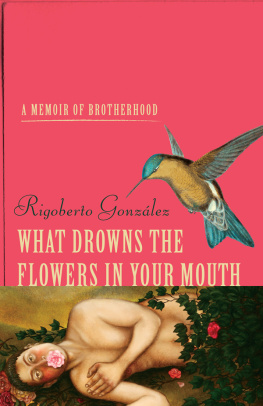

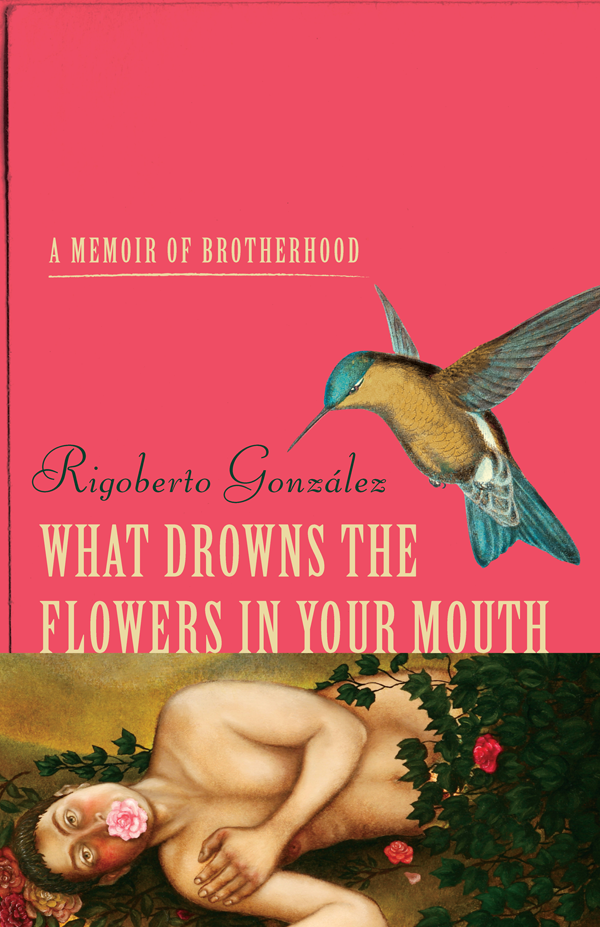

Title: What drowns the flowers in your mouth: a memoir of brotherhood / Rigoberto Gonzlez.

Other titles: Living out.

Description: Madison, Wisconsin: The University of Wisconsin Press, [2018] | Series: Living out: gay and lesbian autobiographies

Identifiers: LCCN 2017042900 | ISBN 9780299316907 (cloth: alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Gonzlez, RigobertoFamily. | Authors, American20th centuryBiography. | Mexican American gaysBiography.

Classification: LCC PS3557.O4695 Z46 2018 | DDC 813/.54 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017042900

ISBN-13: 978-0-299-31698-3 (electronic)

For

Turrtut

OPENING SALVO

The two earliest moments I recall being aware of my younger brother take me back to Zacapu, Michoacn, in the mid-1970s. In the first, Im playing with aluminum toys on the kitchen floor while my mother stands in front of the stove. The sharp corners on the miniature truck keep me focused on the task at hand: creating small collisions as I flutter my lips for effect. I remember my mothers legs underneath a dress, which seems odd because in most of my childhood memories, I picture my mother wearing pants. The dresses I associate with her are hospital gowns, the ones she wore during her quick decline in the 1980s, shortly before her death. But in that memory, shes full of life and inhabiting a domestic scene that made me feel safe and cared for. Our home, so sturdy and large. My mother, always within reach. I remain distracted by my childish game until Im startled by a gurgling above. I look up. Its a small body locked inside a high chair, banging a plate on the plastic tray before him. Hes a funny-looking thinga pale animal with stumpy limbs making awkward sounds like a wounded bird. I stare at him for a few seconds, trying to figure out who brought this into the house and for what purpose. When my mother turns around and puts food in his tiny mouth, I recognize that hes here to stay, that he will compete with me for attention and affection, and since hes clearly more helpless than me, Im going to be asked to keep him company. My resentment grows. Hes going to be a lot of work, this one. But just as quickly,so does my excitement intensify. There are two of us now. And thats like being twice as big, twice as strong, twice as fun. I will teach him. I will lead the way.

The second moment is more vivid. Its rainy season, and the clouds over Zacapu are moody. At any moment, they release their heavy drops over the town, sparing nothing and no one. Thats how my little brother gets caught in the downpour just outside the house. He stands frozen, holding on to his bicycle with training wheels, crying for help. My mother shakes her head as she hands me an umbrella and tells me to bring him in. This gives me a sense of superiority. Not only did I make it home because I gauged the arrival of the rain better than he did, but I had to go back out to rescue him. I pop open the umbrella and walk through the garden, the rain getting louder as it strikes the foliage harder. I open the front gate, its squeak muffled by the noisy weather. When he sees me coming, my brother amplifies his wailing. I shield him immediately and then walk him into the haven of the house, my hand on his soaked back, prodding him forward. Dont worry, Alex, I say. Im here now.

Of those two moments, its the second that flushed into my brain when I received an unexpected phone call from Mxico. It was Guadalupe, my sister-in-law. I was in Montpelier, Vermont, at a writers conference in the summer of 2010. I was strolling absent-mindedly in the peaceful afternoon sun when Guadalupe informed me that my brother, living on the Mexican border town of Mexicali, had been kidnapped. I froze, my feet anchored to the earth as my head spun in circles while I came to terms with the helplessness of the situation. What could I do from so far away? What could I advise except to mutter words that I never imagined would ever come out of my mouth: When they ask for a ransom, tell me, I told my sister-in-law. I will pay it. Ill pay anything. When she burst into tears, I became aware of how surreal it was to be connected to such a scenario through my cell phone while standing in Montpelier with its sky so clear and so clean, its light so bright.And then my body temperature changed and everything around me darkened with shadow.

While I waited to hear back from my sister-in-law, I kept my body locked in place, afraid that if I moved, she wouldnt find me again. My body shook but I couldnt crythere was so much uncertainty about the situation, I thought it would be premature to do so. Instead, I imagined the terrible price that was going to be placed on my brothers life, and tried to determine if I could actually pay it with my paltry savings account and no other family I could reach out to. At that moment, I felt like a failure; I had failed my parents because I had failed to protect my little brother. Eventually I arrived at the most horrific outcome: whether or not I could actually gather the funds, would my brother be allowed to live? I had heard too many heartbreaking stories about my beloved homelands current crisis to have much hope: toes and ears delivered to family members who delayed payment, decapitated bodies to those families that didnt manage to pay, and even to those that did. But other than that, I had no context for what was happening to us. We were not wealthy Mexicans, though that didnt matter anymoreanyone was vulnerable. I suspected that my brother had been targeted because he owned a small business making tacos. It was his dream to have a little side business, and I had helped fund it from afar, thinking that I had done something good for my little brother to help him get ahead. But now, there I was, cold, clammy, and probably responsible for my own brothers abduction. If I lost my brother, I would have no one. Our mother was dead. Our father was dead. To lose my brother would be so unfair after all my other losses.

As I waited for that second call from Guadalupe, I gathered what I could remember about my relationship with my brother, about the ways in which our journeys followed the same path and the ways in which they never intersected. I tried to piece together again the story of our lives as men because everything inside me had just shattered.

DAYS OF HUNGER, DAYS OF WANT

The season of scrambled eggs came upon us on January 6, Three Kings Day. Perhaps it was the holiday spiritthe gifts, the piata, the candythat reminded my mothers younger sisters that it was time to start planning for Holy Week, only three months away. Their appeal, made just when the days excitement quieted down over dinner, made my body stiffen because it was an announcement of the labor to come.