Copyright 2015 by Julian Padowicz

All rights reserved

First edition

Published by Academy Chicago Publishers

An imprint of Chicago Review Press Incorporated

814 North Franklin Street

Chicago, Illinois 60610

ISBN 978-0-89733-919-3

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Padowicz, Julian, author.

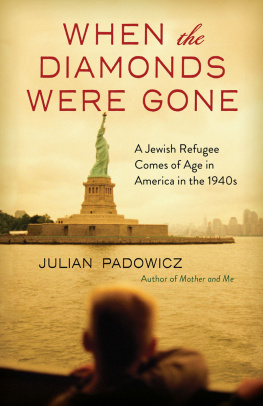

When the diamonds were gone : a Jewish refugee comes of age in America in the 1940s / Julian Padowicz. First edition.

pages cm

ISBN 978-0-89733-919-3 (paperback)

1. Padowicz, JulianChildhood and youth. 2. JewsNew York (State) New YorkBiography. 3. Jews, PolishNew York (State)New YorkBiography. 4. Young menNew York (State)New York Biography. 5. Boarding school studentsBiography. 6. Mothers and sonsNew York (State)New York. I. Title.

F128.9.J5P33 2015

306.8743--dc23

2015001374

Cover design: Sarah Olson

Cover photographs: Sean Justice/Getty Images

Interior design: Nord Compo

Printed in the United States of America

5 4 3 2 1

To my Uncle Arthur and Aunt Julia Szyk

and

Professor Jonathan and Patricia Kistler

each of whom nurtured me in his or her own way

Acknowledgments

Neither this book nor any of its predecessors would have been possible without the help and encouragement of my lovely wife, Donna.

Prologue

This is the fourth and, probably, the last segment of my memoir. Of course, when I was writing the third segment, Loves of Yulian about our stay in Brazil, I thought it to be the last. And for that matter, when I was writing the first one, Mother and Me: Escape from Warsaw 1939, I didnt think I would be doing a sequel. Mother and Me, with its trek over the Carpathian Mountains into neutral Hungary, had such a perfect climax that I thought anything that came after it would be anticlimactic.

But as I thought over our stays in Hungary and, later, Brazil I realized that each of those also had drama and a climax. A very different kind of drama, but a drama nevertheless. Those experiences became A Ship in the Harbor followed by Loves of Yulian, which taught me, as a writer, to look beyond the obvious. And thus I came to realize that the story of an insecure, war-damaged kid plopped into the American educational system, struggling to catch up and trying to live up to his overachiever mothers demands, was not just my quirky childhood but a veritable drama of its own.

So this book came to be. It ends with my graduating college and moving out into an adult world I had come to believe was out of my reach. This climax is certainly not the end of my story. Getting from that callow college graduate to where I now sit, inputting into my laptop the events of my life, has the stuff of several more dramas. But those are stories involving persons now living whose privacy I dont wish to disturb. That I have already imposed on the privacy of several of my peers I take very seriously. I believe that I have not treated anyone unfairly and, frankly, it took considerable editing, on my own initiative, to assure myself of this fact. After this, I will stick strictly to fiction.

Chapter One

I recognized Uncle Arthurs bald head from the deck as our ship came to its excruciatingly slow stop at the dock in New York. Uncle Arthur was my favorite uncle by virtue of having been the one person whose French I had been able to understand when I attended first grade in a French school before the start of the war. That had been some three years earlier, in Warsaw, Poland, and I had spoken no French going in and only a few words coming out. It would be years before Mother explained to me that Uncle Arthur had, actually, just been speaking to me in Polish with a burlesque French accent.

But now a war was raging across Europe. The French school, our home, and the park that my nanny and I had visited daily were probably all gone, and the gangplank that the stevedores were already lifting into position against the still moving hull was about to become the final link in my mothers and my nineteen-month odyssey from the terror of German bombs to safety and, I dearly hoped, normalcy.

I remembered Uncle Arthur as a small, roly-poly man with a round, bald head, a round body, and small hands who played the piano and said things that made grown-ups laugh. But, most importantly to me, Uncle Arthur was a painter of pictures. Before the war, he and Aunt Julia had been living in Paris, where most artists lived. They had come to New York just a year before our own arrival, and we would be staying with them until we got settled. Mother and Uncle Arthur were first cousins, their mothers having been sisters, making him, in reality, my first cousin once removed.

Just how we were to get settled was a mystery to me since my beautiful socialite mother, Barbara, Warsaws Beautiful Basia, could neither read nor write in English, couldnt type, cook, or sew, and had never held a commercial position. We had financed our travel across Europe, to Brazil, and now to New York by the gradual sale of the diamonds Mother had sewn into her clothing when the Soviets first occupied the part of Poland we had fled to when the bombing of Warsaw began. But except for the one remaining diamond in Mothers engagement ring and a round diamond broach of my grandmothers that was of great sentimental value but little monetary worth, the stones were all gone. I dearly hoped that Uncle Arthurs paintings were better appreciated here in America than they had been in France.

Some nineteen months earlier, my beloved nanny, Kiki, had gone home to her own family and my stepfather, Lolek, had put on his reserve officers uniform and gone to the barracks. On the second night of the war we felt the shock of bombs landing around us, and Mother and I left Warsaw, heading away from the attacking Germans. We had traveled in the back of one of the large, window-less delivery vans from Loleks shirt factory along with two of my aunts and two young cousins. After a few days, we found ourselves in the rural southeast of Poland where, two weeks later, the Soviet army marched in, unopposed, while our own army fought the Germans on the west. We went on to spend the next six months living under harsh Soviet occupation.

As food, firewood, and medical supplies grew scarce and the authorities oppressive, my mother proved to be what I would later hear people call resourceful, creative, and courageous in providing for our needs. With her glamorous dyed-blonde looks, her charm, her fluent Russian (my grandmother was Russian), and a quality I would later learn to call chutzpah, Mother had managed to win special favors from the authorities. We had small quantities of sausage and firewood when these were not available to the rest of the population. What it had also achieved was great embarrassment on my part and disapproval of her methods.

Disapproving of Mothers methods had been a major occupation of mine at the time, and to understand it we must go back once more to the prewar period and consider two things. With a crucifix and a photograph of her mother in heaven on the wall over her bed, the rosary beads and little prayer book with the gold-edged pages in her purse, the gold cross on a chain around her neck, and her Sunday attendance at mass, Kiki, my beloved nanny, was Roman Catholic, whereas I and my parents were Jewish. We had no photographs of Moses or prayer books or stars of David. We never went to synagogue. But the real difference was that Kiki was headed for heaven, and we were not. It wasnt that we were any more sinful, though we probably were since Kiki did not sin, or that we didnt practice our Jewish religion, but simply the fact that heaven was exclusive to Catholics. I had Kikis word on that.

Next page