PRAISE

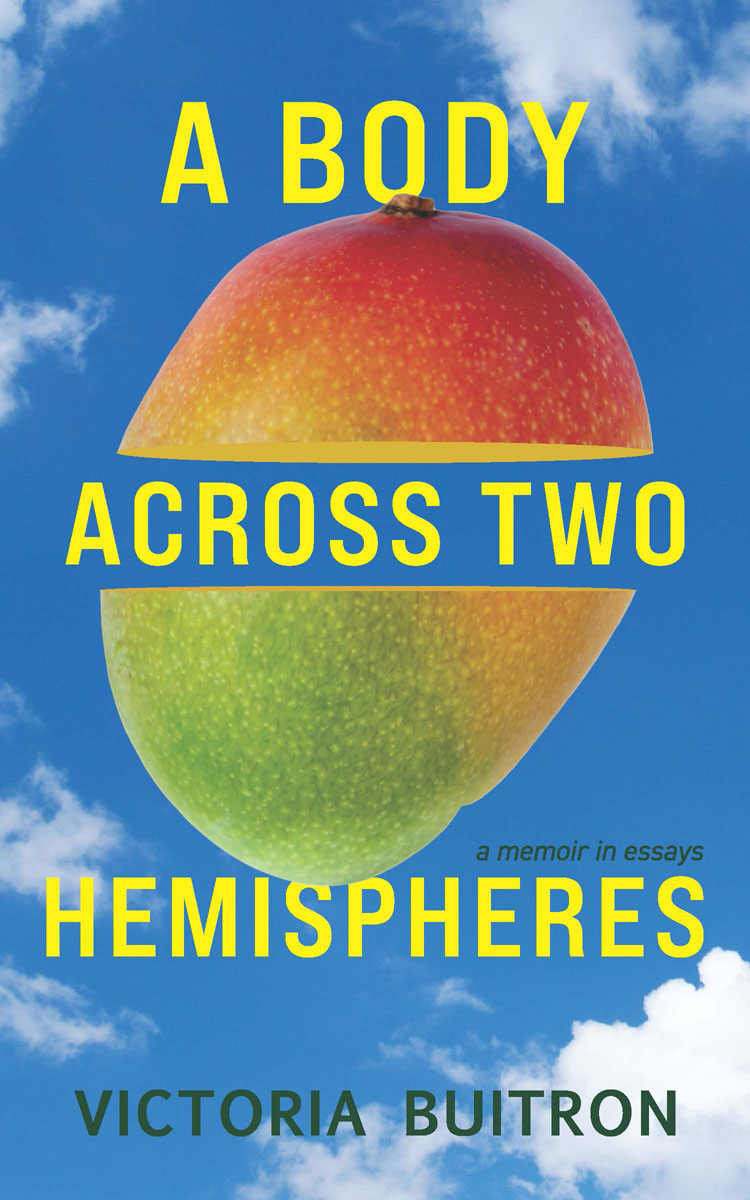

A Body Across Two Hemispheres is a timely book, one many of us need and will be grateful to have read. Theres much to praise about Victoria Buitrons debut. For starters, it showcases the authors formal range within the essay, collecting together lyric pieces, full-fledged narratives, and documentary collageall of which interweave the personal story with political allegory. The book begins with the narrators migration at fifteen, from the United States back to Ecuador, the country of her birth and one she left in early childhood. Centered in accounts of family and of multiple migrations, Buitron moves from adolescence into adulthood, laying claim to who she is by braiding together her various selves. Never shying from what is difficult to reconcile, A Body Across Two Hemispheres introduces an utterly engaging, assured new voice in nonfiction. In her memoir-in-essays, Buitron lays bare various forms of grief but presents them with equal measures of resilience. She posits loveultimatelyas the curative for loss.

S HARA M C C ALLUM , AUTHOR OF N O R UINED S TONE AND T HE F ACE OF W ATER

Woodhall Press, 81 Old Saugatuck Road, Norwalk, CT 06855

WoodhallPress.com

Copyright 2022 Victoria Buitron

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages for review.

Cover design: Danny Sancho

Layout artist: Amie McCracken

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available

ISBN: 978-1-949116-99-1

ISBN: 978-1-949116-62-5

First Edition

Distributed by Independent Publishers Group

(800) 888-4741

Printed in the United States of America

A Body Across Two Hemispheres is a work of nonfiction, but the writer acknowledges that her truth may differ from the truth of others lived experiences. The names of certain individuals and locations in this book have been altered to protect peoples privacy.

For

Segundo Reinaldo Buitrn

The author is grateful to the editors of the publications in which the following essays have appeared:

Cat Whistles and Wolf Calls appeared in Entropy.

Chain Migration appeared in Anomaly.

Changes appeared in Emerge Literary Journal.

Driving by Great Island on Chilly Evenings appeared in (mac)ro(mic) and the title is a play on words inspired by Robert Frosts poem Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening.

First Comes the Egg appeared in Luna Luna Magazine.

Hair in Three Forms appeared in The Bare Life Review.

How to Be an Ecuadorian Girl appeared in The Nasiona.

Let It Burn appeared in Barren Magazine.

Teeth Fragments appeared in Bending Genres and is written after Bear Fragments by Christine Byl.

The First Test appeared in Jellyfish Review.

The Translator appeared in Citron Review.

(Un)Documented is written after The ABCs by Adriana Pramo.

Home may be a mode of living made into a metaphor of survival.

Homi K. Bhabha

CONTENTS

THE SOUTHERN HEMISPHERE

BODYBREAK

On the day of the cleanse, I learned that my shaman and I had similar first names. Before Victor arrived that evening, I wondered what he would look like. I imagined he lived in a hut made of straw and hid his penis with a loincloth that wouldnt cover his butt. I imagined that before the cleanse began, he would slather lines of yellow, green, and splotches of red on his face from crushed roses, stems, and shrubs. Then he would don a headdress made of bones from animals he had killed and feathers from the papagayo. He would walk barefoot because I thought Indigenous Ecuadorians from the jungle didnt wear shoes. My mom didnt care what hed look like, just that he would save me.

On a warm night in 2005, Victor drove through the gates of my home on the Ecuadorian coast in a rusted truck from the previous century. I watched him from behind one of the windows, the houses lights illuminating the stamped concrete yard and his tanned skin as he opened the trucks door and walked out wearing jeans and a T-shirt. He looked like my dad, my math tutor, or the chauffeurs who picked up the rich kids from my high school. He had a stout belly, a mustache that spread above his lip, and thick eyebrows that made his forehead look small. He opened the door to the bed of the truck and began hauling bags into our empty living room. I was convinced that he was a con man, bringing utensils to defraud my parents out of their money in an elaborate scheme. I scoffed and followed my mother, her friend Laura, and my brother into our living room. I wanted to burst out with a laugh, but then it dawned on me why Victor was there in the first place. I looked down at my body, seeing how much it had changed in such a short time.

The cleanse started at midnight and ended when the sun rose. A month before Victor visited us, I had lost my appetite for everything except water. My palate didnt want to taste anything. Before then, food was a form of pleasure as well as sustenance. I would be entranced by the tangy smell of cooked cevichea lemon-based concoction with fish, shrimp, and other seafood seeped in curative powers tailored for the hungover but with equally restorative magic for the sober. Suddenly all ceviche did was trigger my tongue to gag in disgust. Not just ceviche, everything. When the smell of just-cooked chicharrn engulfed my room from the kitchen downstairs, my stomach hurled bile toward my esophagus.

I didnt know it thenwho could?but my body had shut down.

Within the span of a year and a half, I had moved from Norwalk, Connecticut, to the small town I was born in: Milagro, Ecuador. I had gotten on the plane against my will. For a decade, from the ages of five until I was fifteen, Norwalk had been my home. The reason my family moved back to Ecuador was simple. In my hometown of Milagro, my paternal grandfather had gotten sick; my father didnt want to abandon him. But not even five months after our move, my grandfather diedand my father began an affair. I had to learn how to read and write in my first language, a tongue I hardly spoke outside the walls of my home when I had lived in Connecticut. The culture shock rippled through my body like the Ecuadorian earthquakes I would experience. I fell in love with a boy who liked but fake-loved me for eight months.

And thatteenage heartbreakwas the tipping point.

By the time Victor the Shaman entered the gates of my home, my father had returned to the United Statesunable to financially support us in Ecuadorand my mother felt she had no other option but to call on a man with supernatural powers to fix me. Sprinkle in some mourning then add some homesickness, a dash of confusion about what home really meant, plus a sliver of screaming parental fights, and a smidge of a broken heart. My mind and my body had endured too much and just shut down, starting with my stomach.

Mija, you never leave any food, my mom had complained as she grabbed my plate from the dining room table just a few weeks before. Her warm eyes had given me a puzzled look. I made her confusion disappear when I asked her to save it for the following day. The following day became the day after, the day after became a week; suddenly a week became three weeks, and all I could manage to eat were bites of cheese, a strawberry, and a papaya here and there. But nothing cooked, nothing soaked in oil, nothing from an animal. I could bear none of this. By the third week my mother entered my bedroom and sat on the edge of my bed as I lay under the blue-flowered blanket.

Next page