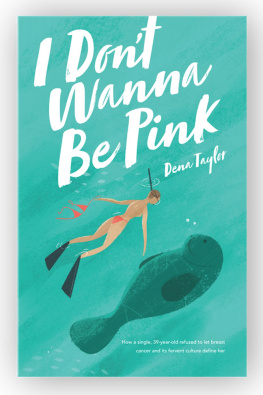

I Don't Wanna Be Pink: How a single, 39-year-old woman refused to let breast cancer and its fervent culture define her

Dena Taylor

Published by Dena Taylor, 2019.

While every precaution has been taken in the preparation of this book, the publisher assumes no responsibility for errors or omissions, or for damages resulting from the use of the information contained herein.

I DON'T WANNA BE PINK: HOW A SINGLE, 39-YEAR-OLD WOMAN REFUSED TO LET BREAST CANCER AND ITS FERVENT CULTURE DEFINE HER

First edition. September 10, 2019.

Copyright 2019 Dena Taylor.

ISBN: 978-1977211644

Written by Dena Taylor.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Beth

We walked and talked for miles, and for a time, up a long, steep hill in uncomfortable shoes

T o write this book , I consulted my personal journals, appointment and procedure notes, and memory. I also tapped the memories of those who helped me along the way and did my best to check facts. A few names have been changed and identifying details altered to preserve anonymity. The medical tests, procedures, and treatment I underwent for breast cancer are personal, relevant to the time period in which the story takes place, and should not be considered medical advice. The choices I made were based on my individual diagnosis and risk tolerance, and do not apply to anyone else. There have been many advancements in breast cancer research and medical care. Consult a medical professional for the latest information.

Its all right

Cause theres beauty in the breakdown

Frou Frou

Let Go

All shall be well, and all shall be well and all manner of thing shall be well

Julian of Norwich

Todays the big day.

Journal Entry

I woke up in a surprisingly good mood. Tad anxious. Actually, I was manic. I thought about the impact a positive mental attitude can have and wondered if I could actually direct the days events by being bright and cheerful. With time to kill before my dear friend Steve picked me up for my appointment, I decided it was worth a try. While I normally detest the perky morning set, I found myself bustling to the neighborhood coffee shop to join themchirping my order to the barista, grinning too hard at a couple of cute guys, and flitting about the outdoor patio before taking a seat. I whipped out my laptop and emailed my sister, Tay, and best friend, Marit, and used lots of exclamation points and smiley emoticons. Back home again, while waiting for Steve, I told the cat how sweet she was, even when she barfed on my couch, and thanked the plants for living with me all these years. It was Wednesday, September 13, 2006.

I looked around my apartment and thought how different everything would or wouldnt be in a few hours time; how most of what we do every day is done with this blind assumption that things will go pretty much how we expect them to. Unless youre a journalist or injury lawyer, no news really is good news.

I spent the last few minutes before Steve arrived sipping a bottle of Dos Equis beer and hanging a new hummingbird feeder on the deck. I dont typically drink beer in the morning, and I know little about birds. In a fit of hope, I told myself that if a hummingbird visited the feeder before Steve knocked on my door, my test results would be negative. But no hummingbird came, and the question lingered: did I or didnt I have cancer?

Of course I didnt. How could I? I was too active, healthy, and young. In fact, in thirty-five days I would be in Italy, celebrating my fortieth birthday with my best friend, a bottle of Chianti, and, if the stars aligned, some handsome, single, and psychologically stable Italian men. It was a big deal, this trip. It symbolized the end of a shaky decade. While I was behind much of the shakingthe crack at acting, the dim romantic choices, the two-thousand-mile move from Seattle to Austin without a jobnot everything had been in my control. There were some surprises too, pink ones, by way of my moms early-stage breast cancer and a suspicious growth in my own breast. But Mom prevailed, and my lesion was benign, and life went on. On the precipice of forty, I had begun to enjoy the fruits of risk and change. I was courting my new town, making friends, loosely dating (and dating loosely), performing in local theater, and earning just enough as a freelance copywriter to cobble together a birthday overseas. I was on a roll and was going to ride that roll all the way to Italy, dunk it in olive oil, and spend a week savoring every bite.

Or was I?

A routine mammogram had revealed a small mass in my right breast, which had led to a biopsy, and, according to my breast surgeon, Dr. Perry, a fifty percent chance that the results would be benign. So, I might have cancer. But I might not. I might go to Italy, I might not. I might live long enough to marry before my parents died, I might not.

Considering the odds in this way was useless and exhausting and made my head hurt. There are always exceptions, benign anomalies do happen, and thats what I decided to focus on until somebody told me different.

Except there had been some needling signs of malignancy along the way, too, thin but peculiar instances that I had noticed but brushed off, one by one.

The first came earlier in the summer by way of Marits trepidation about our trip to Italy. I just feel a little apprehensive, she said, over the phone one day. Im not sure if its because of 9/11 or what, but in all the times Ive traveled to Europe, Ive never felt this way. Its like its not the right time to go or something. After wondering aloud if we should go somewhere else, she acquiesced to Italy, and I didnt give it a second thought.

The second sign came in early September, during my mammogram, which, with all the adjusting and squishing, and stopping-dead for pictures, reminded me of a game of freeze tag, where your breast is always it. After studying the last image of my right breast on the monitor, the technician turned abruptly and looked at me. Our eyes met, and I saw the slightest shift in her gaze, an almost undetectable beat in an otherwise unremarkable moment in time. She quickly looked back to the monitor and said she wanted to get just one more shot. I figured she was just being thorough and stepped up to the plates.

The last sign emerged during my consultation with Dr. Perry, when she described a mass she saw in my films as dark with fuzzy edges. It wasnt just the ominous conglomeration of words, which sounded like something out of a Harry Potter novel; it was how they were delivered. It was as if she had read them and said them before: words belonging to the vernacular of surgeons with hundreds of biopsies and substantiated suspicions under their belts, words with weight. It was as if she knew exactly what was happening in my breast but protocol prevented her from saying it out loud.