Contents

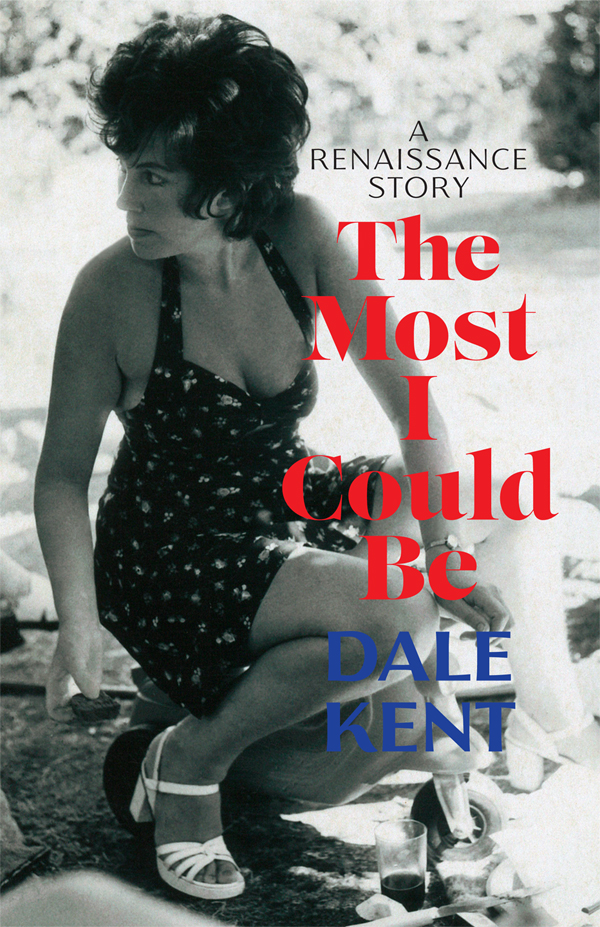

The

Most

I

Could

Be

A

RENAISSANCE

STORY

DALE

KENT

To my daughter Margaret

MELBOURNE UNIVERSITY PRESS

An imprint of Melbourne University Publishing Limited

Level 1, 715 Swanston Street, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia

www.mup.com.au

First published 2021

Text Dale Kent, 2021

Images Dale Kent and various contributors, various dates

Design and typography Melbourne University Publishing Limited, 2021

This book is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 and subsequent amendments, no part may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means or process whatsoever without the prior written permission of the publishers.

Every attempt has been made to locate the copyright holders for material quoted in this book. Any person or organisation that may have been overlooked or misattributed may contact the publisher.

Lyrics and poetry reproduced with permission:

pp. 389: Something Wonderful from The King and I, lyrics by Oscar Hammerstein II; music by Richard Rodgers 1951 by Williamson Music Company, c/o Concord Music Publishing (copyright renewed; international copyright secured; all rights reserved; reprinted by permission of Hal Leonard LLC);

p. 45: Hello, Young Lovers from The King and I, lyrics by Oscar Hammerstein II; music by Richard Rodgers 1951 by Williamson Music Company, c/o Concord Music Publishing (copyright renewed; international copyright secured; all rights reserved; reprinted by permission of Hal Leonard LLC);

p. 67: W.H. Auden, Muse des beaux arts 1940, renewed (reprinted by permission of Curtis Brown, Ltd.);

p. 75: T.S. Eliot, Burnt Norton 1941 from Four Quartets, reproduced with permission of Faber & Faber;

p. 250: A.A. Milne, The Old Sailor The Trustees of the Pooh Properties, 1927 (reproduced with permission from Curtis Brown Group Limited on behalf of the Trustees of the Pooh Properties).

Cover design by Sandy Cull

Cover image courtesy the author

Typeset in Adobe Caslon Pro by Cannon Typesetting

Printed in Australia by McPhersons Printing Group

9780522877663 (paperback)

9780522877670 (ebook)

Contents

Reading Dale Kents stunning memoir is like making friends with the most interesting, intelligent, witty and charismatic person in the room. You never want the conversation to end.

Clare Wright

PROLOGUE

Handicaps of my birth

Of all the exhilarating slogans that galvanised women in the 1970s, determined to change ourselves and the world, the one that really inspired me was: Be the most that you can! Even as a small girl, I was eager to be the most I possibly could. This desire drove my life.

I spent much of it attempting to escape the limitations of my birth. To escape the world of my parentscircumscribed by working-class prejudices and genteel aspirations to self-betterment, and constrained by the intellectual and spiritual straitjacket of the crazy, life-denying doublethink of Christian Science. To escape the dead end of marriage and motherhood, seen as the sole and inevitable destiny of my sex. I would show them I could be anything a man could be. To escape my native land; in my youth, it was taken for granted that if you were any good at, say, writing history or poetry or art criticism or performing on the stage, like Clive James or Robert Hughes or Barry Humphries, you needed to go somewhere elseto England or Americato do it. And if you were a girl, like Germaine Greer or me, youd have to fight tooth and nail to get away.

I got away pretty successfully, or so it seemed. I rejected the fantasies of romantic love, nurtured by novels and movies, which enthralled my mother; I fell in love instead with ideas, with the history and art and literature of Renaissance Italy. I got to study these in the libraries and archives of London and Florence, where I lived for long periods. My dissertation on the rise to power of the famous Medici family was published by Oxford University Press, and put me on the international scholarly map. Subsequent studies of Medici patronage of art and of Florentine friendship and neighbourhood appeared under the imprints of Yale and of Harvard University, at whose Center for Italian Renaissance Studies in Florence I was first a fellow, then several times visiting professor. In my early forties I moved to the United States, where I taught and did research at Berkeley and the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton, at the National Humanities Center of the United States, The J Paul Getty Center for the History of Art and the Humanities, The National Gallery of Art in Washington DC. I lectured and lived all over the United States, at home in the invigorating cultures of Boston, Chicago, Washington, New York and Los Angeles, as one of the leading historians of Florence in the Renaissance.

Compared with my mother and grandmother, I have had a wonderful life. My grandmother attended a one-room school in the Gippsland bush. She left it at eleven, as soon as she was legally allowed, to care for her seven brothers and sisters, because their logger father had been deserted by his wife, who was said to be flighty. After Grandma moved to Melbourne and married, at eighteen, she raised her husbands numerous younger siblings, and took in washing and sewing to supplement his meagre income as a toolmaker in a Footscray metal-working factory. My mother also left school at eleven, to stay home with her mother, until she married a man ten years older than herself, with a degree in engineering. Like the mothers in Austens and Eliots novels, she was obsessed with marrying her daughters well, lest we slip back into the working classes, who have nothing, are nothing, and never will be anything! I did and became things Mum and Grandma never even dreamed of.

But the experience of being female, and the view of myself and love and sex that I inherited from them, and internalised, was crippling from the start. By the time I was nine or ten, I was appalled by the way the men and women of my family treated one another, although it was not extraordinary by the standards of their time and class. Each generation of women strove to subdue the next with the same oppressive tactics to which she had been subjected, and they revenged themselves against the men who subjugated them, as by right, by emasculating them, and depriving them of sex. I didnt want any part of this. I grew up hating the fact that I was a woman.

As for men, I knew nothing about them. Until I went to university I was hardly ever left alone with one. I dwelt in the make-believe world of Mums romantic dreams, instilled in my adolescent heart over hours with her in the dark in the red-plush depths of our local Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer movie theatre, or reading in bed the Georgette Heyer Regency romances she pressed upon me. Despise them as I might, I never managed to liberate myself entirely from these fantasies. I will always remember my shock of grateful recognition when, in The Female Eunuch