Coulton's expedition into Fourteenth-century England and the life of Chaucer, first published in 1908, remains an excellent resource for any reader interested in gaining an understanding of that great writer's world. Beautifully illustrated, the book details Chaucer's service as a squire, his ambassadorial career, his Canterbury Pilgrimage and his writings, never omitting the social and political realities which shaped his life.

CHIVALRY - Edgar Prestage

CHRONICLES OF THE CRUSADES - Henry G. Bohm

THE SPIRIT AND INFLUENCE OF CHIVALRY - JOHN BATTY

ROMANCES OF CHIVALRY - John Ashen

SOCIAL LIFE IN BRITAIN FROM THE CONQUEST TO THE REFORMATION - G. G. Coulton

SPANISH AND PORTUGUESE ROMANCES OF CHIVALRY - Henry Thomas

THE ALEXIAD OF THE PRINCESS ANNA COMNENA - Elizabeth A. S. Dawes

THE BOOK OF THE ORDER OF CHIVALRY - Alfred T. P. Byles

THE HISTORY OF CHIVALRY OR KNIGHTHOOD AND ITS TIMES, VOL 1 - Charles Mills

THE HISTORY OF CHIVALRY OR KNIGHTHOOD AND ITS TIMES, VOL 2 - Charles Mills

THE SOCIAL HISTORY OF CHIVALRY - F. Cornish

CHAUCER AND HIS ENGLAND - G. G. Coulton

AN ANGLO-SAXON READER IN PROSE AND VERSE - Henry Sweet

MYTHS AND LEGENDS OF THE MIDDLE AGES - H. A. Guerber

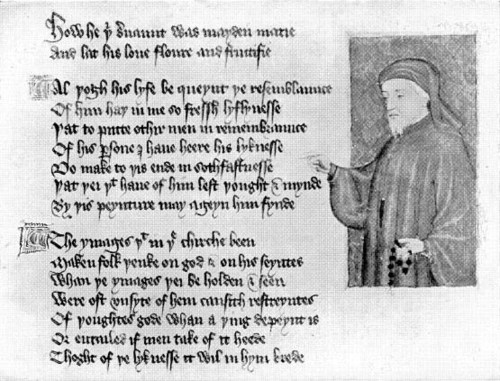

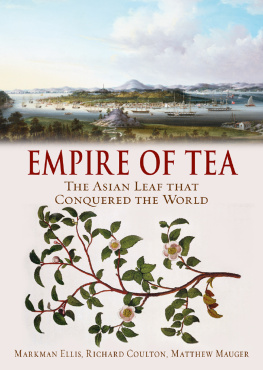

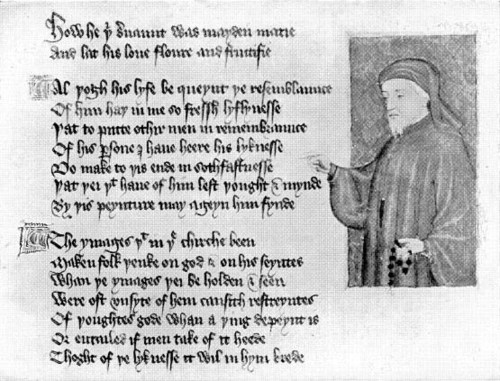

PORTRAIT OF CHAUCER

PAINTED BY ORDER OF HIS PUPIL THOMAS HOCULEVE, IN A COPY OF THE LATTER'S REGEMENT OF PRINCES. THE HAIR AND BEARD ARE GREY, THK EYES HAZEL: HE HAS A ROSARY IN HIS LEFT HAND AND A BLACK PENCASE OR PENKNIFE HANGS FROM HIS NECK

First published in 2004 by

Kegan Paul Limited

Published 2013 by Rautledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, NewYork, NY10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & francis Group, an informa business

Kegan Paul, 2004

All Rights reserved. No part of this hook may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electric, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying or recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

ISBN: 0-7103-0923-6

ISBN: 978-0-710-30923-5 (hbk)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Applied for.

N O book of this size can pretend to treat exhaustively of all that concerns Chaucer and his England; but the Author's main aim has been to supply an informal historical commentary on the poet's works. He has not hesitated, in a book intended for the general public, to modernize Chaucer's spelling, or even on rare occasions to change a word.

His best acknowledgments are due to those who have laboured so fruitfully during the last fifty years in publishing Chaucerian and other original documents of the later Middle Ages; more especially to Dr. F. J. Furnivall, the indefatigable founder of the Chaucer Society and the Early English Text Society; to Professor W. W. Skeat, whose ungrudging generosity in private help is necessarily known only to a small percentage of those who have been aided by his printed works; to Dr. R. R. Sharpe, archivist of the London Guildhall; to Prebendary F. C. Hingeston-Randolph and other editors of Episcopal Registers; to Messrs. W. Hudson and Walter Rye for their contributions to Norfolk history; and to Mr. V. B. Redstone's researches in Chaucerian genealogy. His proofs have enjoyed the great advantage of revision by Dr. Furnivall, who has made many valuable suggestions and corrections, but who is in no way responsible for other possible errors or omissions. The many debts to other writers are, it is hoped, duly acknowledged in their places; but the Author must here confess himself specially beholden to the writings of M. Jusserand, whose rare sympathy and insight are combined with an equal charm of exposition.

He has also to thank Dr. F. J. Furnivall, Messrs. E. Kelsey and H. R. Browne of Eastbourne, and the Librarian of Uppingham School, for kind permission to reproduce seven of the illustrations; also the Editor of the Home and Counties Magazine for similar courtesy with regard to the plan of Chaucer's Aldgate included in a 16th-century survey published for the first time in that magazine (vol. i. p. 50).

EASTBOURNE

CONTENTS

LIST OF PLATES

THE HOCCLEVE PORTRAIT OF CHAUCER

From the Painting in The Regement of Princes

CHAUCER AND HIS ENGLAND

O born in days when wits were fresh and clear,

And life ran gaily as the sparkling Thames !

F EW men could lay better claim than Chaucer to this happy accident of birth with which Matthew Arnold endows his Scholar Gipsy, if we refrain from pressing too literally the poet's fancy of a Golden Age. Chaucer's times seemed sordid enough to many good and great men who lived in them; but few ages of the world have been better suited to nourish such a genius, or can afford a more delightful travelling-ground for us of the 20th century. There is indeed a glory over the distant past which is (in spite of the paradox) scarcely less real for being to a great extent imaginary; scarcely less true because it owes so much to the beholder's eye. It is like the subtle charm we feel every time we set foot afresh on a foreign shore. It is just because we should never dream of choosing France or Germany for our home that we love them so much for our holidays; it is just because we are so deeply rooted in our own age that we find so much pleasure and profit in the past, where we may build for ourselves a new heaven and a new earth out of the wreck of a vanished world. The very things which would oppress us out of all proportion as present-day realities dwindle to even less than their real significance in the long perspective of history. All the oppressions that were then done under the sun, and the tears of such as were oppressed, show very small in the sum-total of things; the ancient tale of wrong has little meaning to us who repose so far above it all; the real landmarks are the great men who for a moment moulded the world to their own will, or those still greater who kept themselves altogether unspotted from it. Human nature gives the lie direct to Mark Antony's bitter rhetoric: it is rather the good that lives after a man, and the evil that is oft interred with his bones. The balance may not be very heavy, but it is on the right side; man's insatiable curiosity about his fellow-men is as natural as his appetite for food, which may on the whole be trusted to refuse the evil and choose the good; and, in both cases, his taste is, within obvious limits, a true guide. It is a healthy instinct which prompts us to dwell on the beauties of an ancient timber-built house, or on the gorgeous pageantry of the Middle Ages, without a too curious scrutiny of what may lie under the surface; and at this distance the 14th century stands out to the modern eye with a clearness and brilliancy which few men can see in their own age, or even in that immediate past which must always be partially dimmed with the dust of present-day conflicts. Those who were separated by only a few generations from the Middle Ages could seldom judge them with sufficient sympathy. Even two hundred years ago, most Englishmen thought of that time as a great forest from which we had not long emerged; they looked back and saw it in imagination as Dante saw the dark wood of his own wanderingsbitter as death, cruel as the perilous sea from which a spent swimmer has just struggled out upon the shore. Then, with Goethe and Scott, came the Romantic Revival; and these men showed us the Middle Ages peopled with living creaturesbeasts of prey, indeed, in very many cases, but always bright and swift and attractive, as wild beasts are in comparison with the commonplace stock of our fields and farmyardsbright in themselves, and heightened in colour by the artificial brilliancy which perspective gives to all that we see through the wrong end of a telescope. Since then men have turned the other end of the telescope on medieval society, and now, in due course, the microscope, with many curious results. But it is always good to balance our too detailed impressions with a general survey, and to take a brief holiday, of set purpose, from the world in which our own daily work has to be done, into a race of men so unlike our own even amid all their general resemblance.