Contents

Page List

Guide

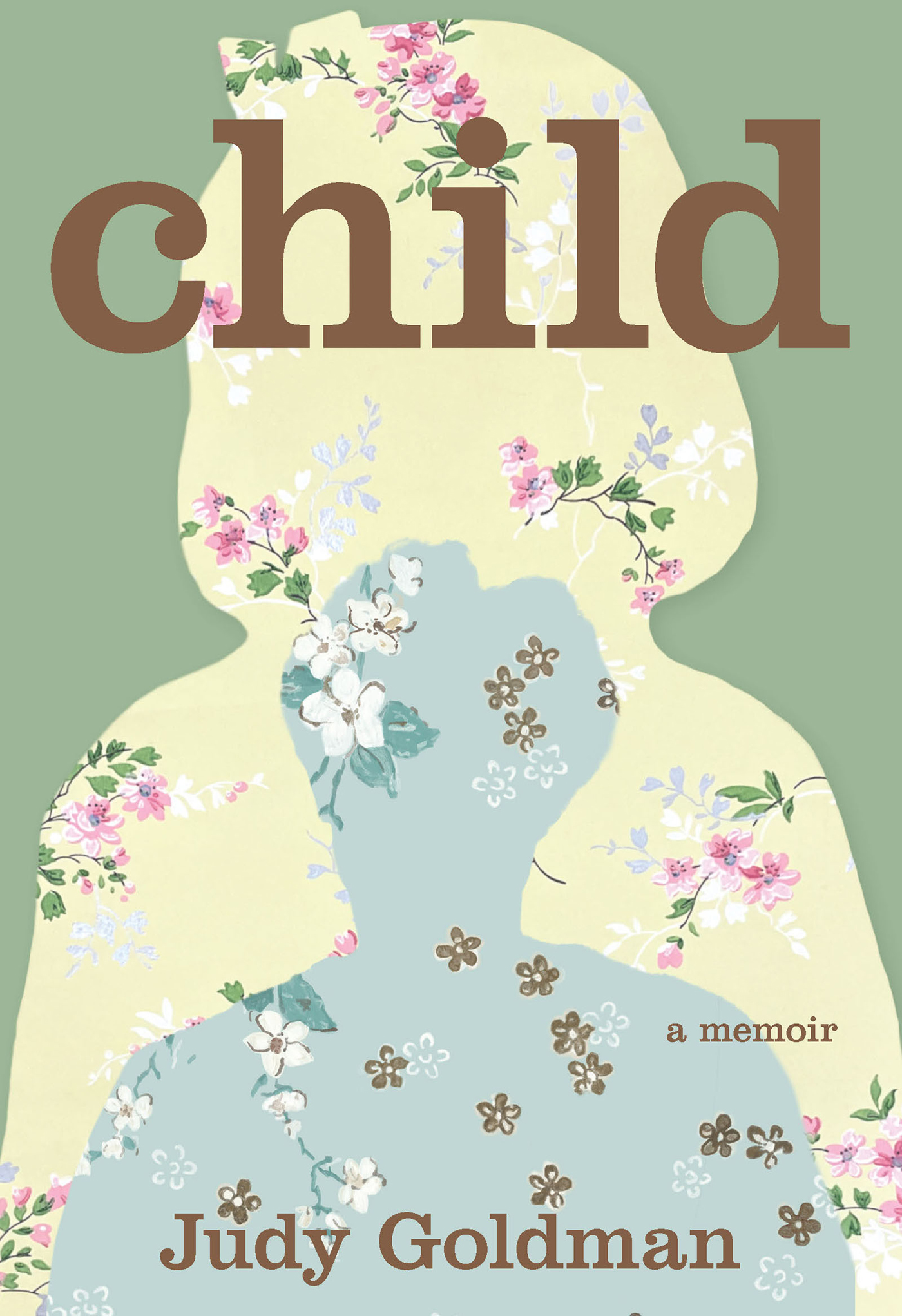

child

Also by Judy Goldman

NONFICTION

Together: A Memoir of a Marriage and a Medical Mishap Losing My Sister

FICTION

Early Leaving

The Slow Way Back

POETRY

Wanting to Know the End

Holding Back Winter

child

a memoir

Judy Goldman

2022 University of South Carolina

Published by the University of South Carolina Press

Columbia, South Carolina 29208

www.uscpress.com

Manufactured in the United States of America

31 30 29 28 27 26 25 24 23 22

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data can be found at http://catalog.loc.gov/.

ISBN 978-1-64336-283-0 (paperback)

ISBN 978-1-64336-284-7 (ebook)

Front cover design by Laurie Smithwick / @lauriesmithwick

Authors Note on Text: I have used a word in two different chapters of this memoir that is deeply offensive to me and will, no doubt, also be offensive to you. In each instance, the word is part of dialogue. In one, its spoken ironically; Ive chosen to include the word there because of the context and because of my admiration for the person who used it. It also appears in that chapter as part of a thought I had as a child. In the other chapter, I included the word to convey the full horror of the moment.

For Mattie Culp

This book is because of you. But then, so much that is good about my life is because of you.

Mattie, around the time she came to work for the Kurtz family, circa 1944. Photograph courtesy of Judy Goldman.

Contents

Prologue

Like thousands of white southerners in my generation, I was raised by a Black woman who had to leave her own child behind to work for a white family. At least, thats what I always believed. It wasnt until Id written several drafts of this book, then happened upon unsettling information which had been in these pages all along, that I started asking questions of the people who were still alive. And thats when I learned there was more to the story.

A story that, of course, encompasses race. But also childhood. And all that occurs before we grasp the true scale of the grown-up world.

These are micro-narratives. Fragments that form a love story. A jumbled-up love story. The ordinary, moment-by-moment story of Mattie Culp and mefrom the time I was three until her death sixty-three years later.

Memory is two parts.

First, the re-inhabiting:

The light outside our window is fading. Mattie and I sit side by side on the edge of the bed. She takes off her glasses and places them on the Bible on her bedside table, leans closer to me so that I can rub her pillowy shoulders, mostly her right shoulder, the one that always goes stiff after a day of work. My small fingers soften the knots that need softening. She whispers, You got magic in your hands.

Then, the interpreting:

Our love was unwavering. But it was, by definition, uneven. She was hired by my parents to iron my dresses and fry my over-light eggs. But that doesnt begin to describe the marvel she was to me. And what was I to her? How to be clear and un-idealized about that?

At times, Ive hesitated to even talk about us. And, if I couldnt talk about us, I sure couldnt write about us. Our relationship was lovely in an unlovely context. So many contradictions. If I say one thing, I could be denying something else. My opinions might really just be assumptions, any innocence I express simply defensiveness. Nothing is ever simple.

But Ive wanted to tell this story for as long as I can remember. Im eighty now. There wont be a better time for me to get the details down. To try to understand the complications of a key relationship in my life. To answer that voice saying yes, go ahead, write our story, before its lost.

In the beginning, Mattie and I shared a bed, a double bed that felt as wide as the world.

She came to work for us in 1944, when she was twenty-six and I was three. My sister was six. My brother was eleven. Mother was thirty-five. My father, thirty-six.

It was unusual in Rock Hill, South Carolina, for a maid to live in. We knew only two other families who had someone actually living in the house. The pediatrician who took care of my brother, sister, and me had a live-in maid. The young widower across the street, who owned the Pix movie theater and piloted his own plane and planted palm trees in the front yard of his stucco Hollywoodlike house, so different from everyone elses househe had a live-in maid to look after his daughter. The maids who lived with these families went to their own homes on weekends. Mattie did not have her own home. Our home was her home.

I never questioned why she didnt just do day work, like other maids. Never asked her how she could just move in with a family of strangers and leave her daughter elsewhere. Never asked anything about the arrangements shed made. I didnt know why my parents wanted someone to live in. Didnt know why we wouldnt just hire a day worker like everyone else.

I only knew this: the way Mattie wrapped her head in a faded, flowered scarf before bed, the sureness of her body beside me, her soft and generous bosom, her soft and generous everything, her quiet hymns Jesusing me to sleep.

Our room was square and airy. My side of the bed was against the wall. At the foot of the bed, a window overlooked our side yard and the neighbors side yard, their swing set and sandbox, and farther back, their clothesline; even farther back, their henhouse, not housing hens anymore, so we used it for the plays I created and starred in and made all the kids in the neighborhood either act in or pay to see. Long, white, gauzy curtains half-hid the window but still let the light in. Mattie washed those curtains when she decided they needed washing, hung them on the line to dry, starched and pressed them on the X-legged ironing board that stayed open beneath the windowsill.

On her side of the bed, a table and lamp. Her Bible rested on a starched white doily that covered the tabletop. Beside the Bible, a small jar of the hair cream she used every night before she wrapped her scarf around her head. When she unscrewed the top of the jar, a burny smell filled the room and tickled my nostrils.

On the other side of a window that faced the front yard was a cane-bottomed chair and next to that, our dresser. One drawer held my clothes, the other two, Matties. Her hairbrush, hand lotion, face powder, powder puff, and small, jewel-decorated box holding her earrings were arranged neatly on top of our dresser, along with my comb, brush, and jewel-decorated box, holding my hair ribbons. Our matching jewelry boxes had been Christmas gifts from Mother one year. Mattie got ready in the morning much faster than Mother, who sat at her dressing table and put on moisturizer, foundation, powder, rouge, eyebrow pencil, and lipstick. Mattie just took off her scarf, patted her hair in place, tucking in strays, and, if we were going downtown that morning, she dabbed the puff in her powder and ran it over her face. Otherwise, fixing her hair was all she did to get ready for the day.