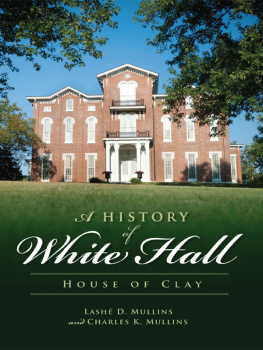

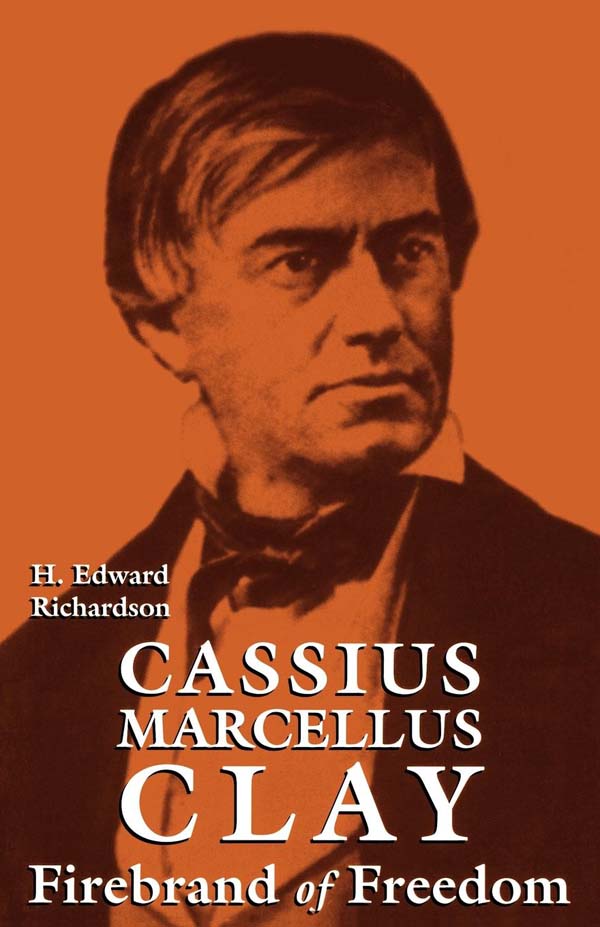

CASSIUS MARCELLUS CLAY

Cassius

Marcellus

Clay

Firebrand of Freedom

H. EDWARD RICHARDSON

Copyright 1976 by The University Press of Kentucky

Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth,

serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre

College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University,

The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College,

Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University,

Morehead State University, Murray State University,

Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University,

University of Kentucky, University of Louisville,

and Western Kentucky University.

All rights reserved.

Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky

663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008

www.kentuckypress.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Richardson, H. Edward (Harold Edward), 1929

Cassius Marcellus Clay : firebrand of freedom / H. Edward

Richardson.

p.cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-8131-0861-6 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Clay, Cassius Marcellus, 18101903. 2. PoliticiansUnited

StatesBiography. AbolitionistsKentuckyBiography. I. Title.

E415.9.C55R47 1996

973.6092dc20 [B] 95-48312

ISBN-13: 978-0-8131-0861-2 (pbk. : alk. paper)

This book is printed on acid-free recycled paper meeting

the requirements of the American National Standard

for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America.

| Member of the Association of

American University Presses |

For Shawn Edward Richardson

& Jill Calvert Richardson

Contents

Illustrations follow

Preface

CASSIUS MARCELLUS CLAY was a paradox in history. Born to wealth, he was an upholder of the oppressed. Clearly he was a man of intellect, and yet it was the passion of his words and actions that seared each central event of his life into the memories of his contemporaries. Though one of the great men of his age, he stood apart from all. Isolated and eccentric in his old age, he died to become an ageless legend, forever green in human memory.

Much of the meaning of Clays life lay in its supreme individualism, inseparable elements of which were his personal style, his flair, his charismawords that would have paled in abstraction beside the living man. Remembering Clay, Justice John M. Harlan wrote: There is a more striking combination of manly beauty and strength in his face than in the face of any man whom I ever saw. I always had the highest regard for his integrity of character, his manliness, and his fidelity to his own convictions.

In this biographical essay I have endeavored above all else to avoid treating Clay as a Kentucky Quixote, on the one hand, or as a savior of the Union, on the other, although there is some truth in both views. Rather, I have endeavored to see Clay as his own records reveal him; at the same time I have attempted to view him in the setting of history and to present his life in a systematic narrative against that record of his times.

My research has led me to a view of Clays life and career at variance with general opinion. Briefly stated, my contention is that his ideas were in principle consistent throughout his life. Certainly he intended from his early manhood to deal slavery a deathblow. But Clay was more than an emancipationist. He was committed to what he called some great principle of human happiness; before all things, Clay was a freedom hunter. His commitment to freedom of the press, for example, was as great as the martyred Lovejoys.

Although Clays letters, regrettably, are as yet uncollected, and further research remains to be done, I hope my efforts will throw light upon some previously obscure areas and correct some earlier misreadings of Clays life. I hope also that this book will help to make Americans more aware of one of the nations heroic figures.

While I have attempted to distinguish myth from fact, I have not thought it proper to ignore myth as it relates to Clay. Gilbert Murray describes the myth motif as a strange, unanalyzed vibration below the surface, an undercurrent of desires and fears and passions, long slumbering yet eternally familiar. Though myths may seem strange, there is yet that within us which leaps at the sight of them, a cry of the blood which tells us we have known them always. In Clays life, myth persists with such force that it reminds us, allowing for its exaggerations and distortions, that history, as La Rochefoucauld said, never embraces more than a small part of reality.

My first knowledge of Clay goes back to the 1930s, to the Madison County Courthouse in Richmond, where I heard the few remaining Civil War veterans and their many admirers of all ages talk about him. I remember them well. They hitched up their splint-bottom chairs in the shade of August maples. Their barlow knives delicately pared cedar shavings that, like little wooden springs, danced to the ground. The older men could not negotiate such complicated whittling but rested their hands on the crooks of hickory canes. When the talk turned to Cash Clay, the whittling stopped. Knives and canes became punctuation marks as the old men grew eloquent. I remember their faces all aglow behind saffron-tinctured beards, their eyes burning under bushy white browsa sudden excitement in the hot air.

Rotten shame the fool killer didnt get around to Old Cash before he died a natural death, they reckoned, but he was a heller with a bowie knife. To them his public life was a crucible of volatile national issues, his private life a taunting outrage. Yet when the talk grew heated, when their faces shown hot as the isinglass of a roaring pot-bellied stoveand the most vehement critic was deep in bloody narrative, painting in exquisite detail the savage ferocity with which the old general defended his damned principlesinvariably a strange undercurrent of awe, not unakin to admiration and envy, would sweep through those who remembered him.

For these reasons, I suppose, I do not recall a neutral statement ever made about him. Madison County was then overwhelmingly Democratic, and my mother was one of the few Republicans I knew. General Clay was a famous Republican, or if I were to believe those gray-beards, an infamous Republican. In this community of traditional morality, General Clays sins had found him out. He accumulated a wide range of colorful sobriquets: old rip, and worse, cradle-robber who bought dolls for his child bride to play with. And so on summer afternoons, the courthouse idlers recited their fathers and grandfathers denunciations of Clay as an autocrat of hell. For nineteenth century proslavery Democrats this meant that he was, among other accomplishments, a Republican. Worse than that, he was a black Republicanoften a black-hearted rascal. Black was no simple metaphor: Old Cash had actually voted the blacks. At Foxtown he had armed himself and marched whole coffles, 60 or 80 at a time, to the polls.