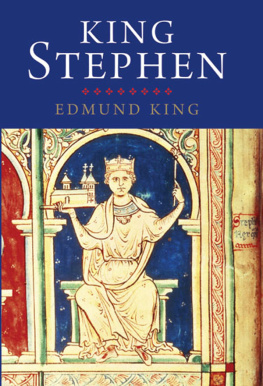

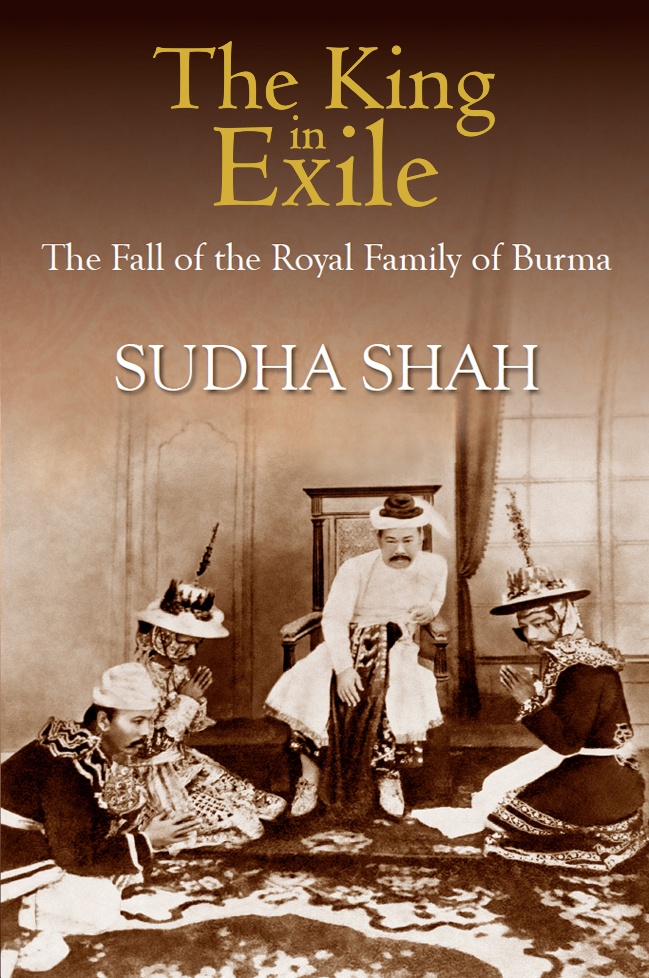

T HE K ING IN

E XILE

The Fall of the Royal Family of Burma

Sudha Shah

With 32 pages of photographs/illustrations

For my parents, Sheila and Janak Malkani

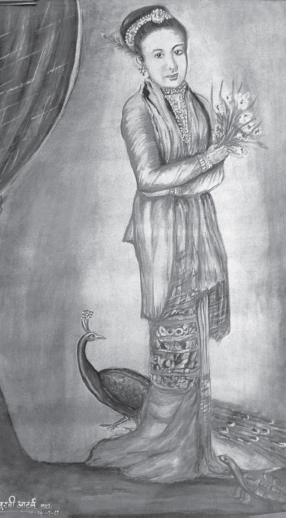

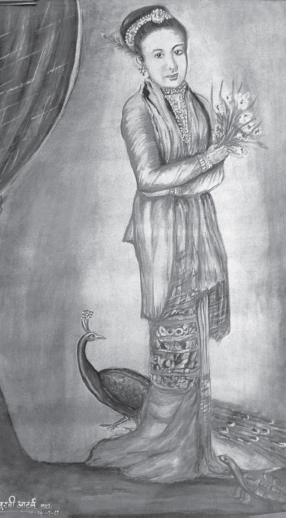

In memory of Ashin Hteik Su Myat Phaya Gyi, the First Princess

Copyright (of photograph of portrait): Vimla Patil

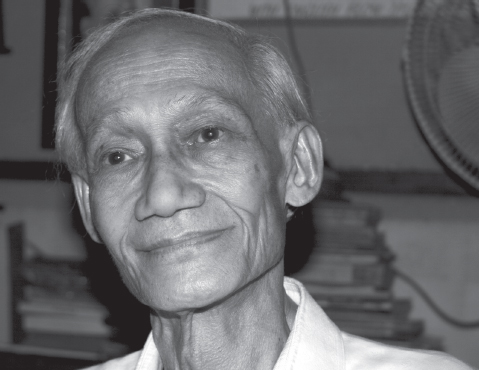

In deep appreciation for all the help, support and warmth given to me by Prince Taw Phaya Galae (Prince Frederick), also known as U Aung Zae, and affectionately called Taw Taw. A nationalist, an entrepreneur, a writer, a history researcher, an English teacher, he was a man of quiet dignity and great charm. In spite of his failing health, he generously helped me with my research. Over phone conversations and in emails, he commented that he hoped to live to read my book. This was not to besadly, he passed away on 18 June 2006.

Prince Taw Phaya Galae was the grandson of the last king of Burma, King Thibaw, and his wife, Queen Supayalat, and the son of the Fourth Princess, Ashin Hteik Su Myat Phaya Galae, and her husband, Ko Ko Naing.

Picture taken by author on 27 February 2005 at Prince Taw Phaya Galaes home in Yangon

CONTENTS

T hibaw, the last king of Burma, belonged to the Konbaung dynasty, a line of rulers known as Kings who rule the Universe and treated as demi-gods by their subjects. His wife, Queen Supayalat, had great influence over him and is said to have been the true ruler of the kingdom during their seven-year reign.

In late 1885, after defeat in a war against Britain, King Thibaw, the heavily pregnant Queen Supayalat, their two very young daughters, and the kings junior queen, Supayagalae, were exiled to India. Here, in the culturally alien and remote town of Ratnagiri, they lived for over thirty years.

The First, Second, Third and Fourth Princesses, so called for the sake of brevity by the various British officers in charge of the family during their exile (the princesses, as per custom, were known by lengthy titles and not common names), were brought up in Ratnagiri by parents mourning their loss and nursing their wounds. Like their parents, the princesses were not allowed to interact freely with the residents of Ratnagiri. There was no question of them enrolling at a local school or playing with the town children; even if the British had permitted it, it is unlikely their parents would have. So they lived, attended to by an army of servants and assistants, until the princesses were all in their thirties. By this time, two of them had fallen in love with highly unsuitable men, and all four of them had been endowed with a deep awareness of their ancestry, a sense of entitlement, and a feeling of bereavement. None of them had received the kind of exposure or education necessary to adequately equip them for life in the outside world.

King Thibaw died in 1916 without ever setting foot on his homeland again. His junior queen had died a few years before him. Both were entombed in Ratnagiri, where their mortal remains lie to this day. In 1919, not long after World War I (191418) concluded, Queen Supayalat and the princesses were permitted to return to British-occupied Rangoon.

This book tells the story of King Thibaw, his wives, his daughters and his grandchildren. It has not been written as a work of fictionI found the actual story too captivating to add any embellishments. (The bizarre twists and turns their lives sometimes took were truly stranger than any credible fiction could ever have been!) The raison dtre of the book is to provide an insight into, first, how an all-powerful and very wealthy family coped with forced isolation and separation from all that they had once known and cherished; and, second, how the family lived once the exile ended. When I first started researching for this book, I thought I would end with the death of the Third Princess, that is, on 21 July 1962. But the more I delved, the more I realized that for a sense of completion and closure one needed to examine the lives of the princesses children as well, for the childrens lives were inextricably intertwined with those of their mothers, and they too were impacted by the deposition, the exile, and their lineage.

Part I depicts the life of the king and queen during their reign. I felt this background was essential to put into context the royal familys life during and after the exile. My sources for Part 1 include two well-researched, fictionalized accounts of historical events which, I believe, accurately represent the essence of what actually happened. The authors of both these books (The Lacquer Lady and Thibaws Queen) interviewed (inter alia) maid(s) of honour who served under Queen Supayalat. Conversations and facts reproduced from these sources have been clearly identified in the endnotes (as have all my other sources).

Parts II and IIIthe heart of my research and of my bookdetails the familys life during and after the exile. No fictionalized source has been used for these parts (except for an unpublished manuscript by James Halliday aka David Symington who was collector of Ratnagiri about ten years after the departure of the royal family from Ratnagiri. Two brief bits of information have been used from this sourcethe first is regarding Mr Tennants infatuation with the Fourth Princess, and the second is about the notice put up at the Royal Residence after the kings death). However, I have depended muchparticularly for Part IIIon peoples memories (on their verbal and written accounts), and memories, as we know, are informed by the perceptions of the narrator. When differing, and sometimes even contradictory, versions of the same occurrence have been narrated, the version that has seemed the most credible to me has been worked into the book. Ever so often, however, it has been impossible to sift actual facts from those based on peoples assumptions, extrapolations and imagination. Since so much of what happened was not documented, and since many of the protagonists of this story lived long ago, I have often had to depend on just one source for a piece of information.

Vikram Seth wrote in his book Two Lives: Every even-handed biography of a completed life has to deal with private matters and to present its subject as fully as possible, even if the subject, when alive, might have preferred to keep these matters obscuredor at least not open to the world. While writing this book, I have had to occasionally mentally wrestle with whether or not to include certain facts (particularly for Parts II and III). It is apparent that family descendants I interviewed sometimes have had a similar conflictwhat to divulge to me and how much, what to gloss over or totally conceal. There are certain matters the family would perhaps have preferred not revealed, but by not including them would this biography have been at all meaningful? In making a decision, I have tried to consider whether the matter would add something consequential to either our understanding of the people involved or the events that occurred. If the answer is yes, I have included it, but with as much sensitivity as I could.

Next page