Table of Contents

Guide

Table of Contents

For my family

prologue

LETTER TO AN UNBORN SON

It began with a burst of sunshine, a bad taste in the air, a hiccup as one cell tried to transfer its data to another. It began long before me, your mother. A genetic disorder, carried invisibly by mothers and passed to sons, snakes through our family tree. It is a fragment of history we can trace, a tiny bundle of stories floating in our blood.

The primary symptoms of your condition are sparse hair, peg- or cone-shaped teeth, and the inability to sweat. At every moment, a normal human body engages in a struggle against death by heat or cold. A person with sweat glands fights overheating with perspiration. But a body without sweat glands flies on faith, staving off death without the checks and balances of normal human physiology.

The secondary symptoms include distinctive facial features, such as dark circles around the eyes and a saddle-nose deformity: a deep depression where the bridge of the nose should be. Sufferers have trouble breathing, so they have trouble sleeping, and so they have trouble keeping awake. Because of their tired appearance and sallow skin, they often appear ill, even when they feel fine. On the other hand, many often are ill. Immunodeficiency associated with the condition may lead to a lifetime of infections. All this leads others to view sufferers of this disorder as weak, incompetent, possessed of problems.

It is called hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia, or HED. The older a man with this disorder gets, the more trouble he may have getting his body to respond to medication. The more exhausted he may become, the worse for his self-esteem. Despite the fact that HED is said not to limit life expectancy, I have learned this: The more pain a sufferer feels, the more he may wish to die.

As I tell you these stories, you are nothing but a phantom. You are a strange presence, a spirit somehow alive. By turns I feel compelled to greet you, to apologize to you, to nurture you, and to frighten you away. You have taken up a place in my heart. Before long, you might take up a place in my womb. We could find ourselves thus: you, a fetus, with a skull the size of a cherry and a wisp of body trailing. Me, and your father, deciding whether to bring you into the world.

Soon after our wedding, you came into my dreams: a blond-haired baby boy, with a round face and little spectacles bespeaking your strange intelligence. We walked on the shore. We lay in the sand. The air blew wet and salty. You told me to look for the light show of angels and to listen for wind. You told me to watch for fire. You warned me before the swoop and strike of talons. Sometimes, you simply held me, clinging in a long hug like a sleepy koala. And one winter night I awoke with your words in my ears, crystalline: Dont rule me out.

As you spoke, your father tossed and sweated beside me. Dan, my beloved. His cold skin drenched our bedsheets. Im trying to save our children, came his hoarse voice in the darkness. They keep falling into their ancestors graves.

What did you mean, dont rule me out? The phrase means to remove from consideration, to prevent. But when you said it, I heard, Dont take this lightly. Dont make it easier than it is. Dont take one look at me and say, Forget it. Or So what? Take many long looks at me, and at the lives that refract into mine, and decide painstakingly. Decide with all of the care and love and mercy you can find.

And so, you sent me on this journey.

part one

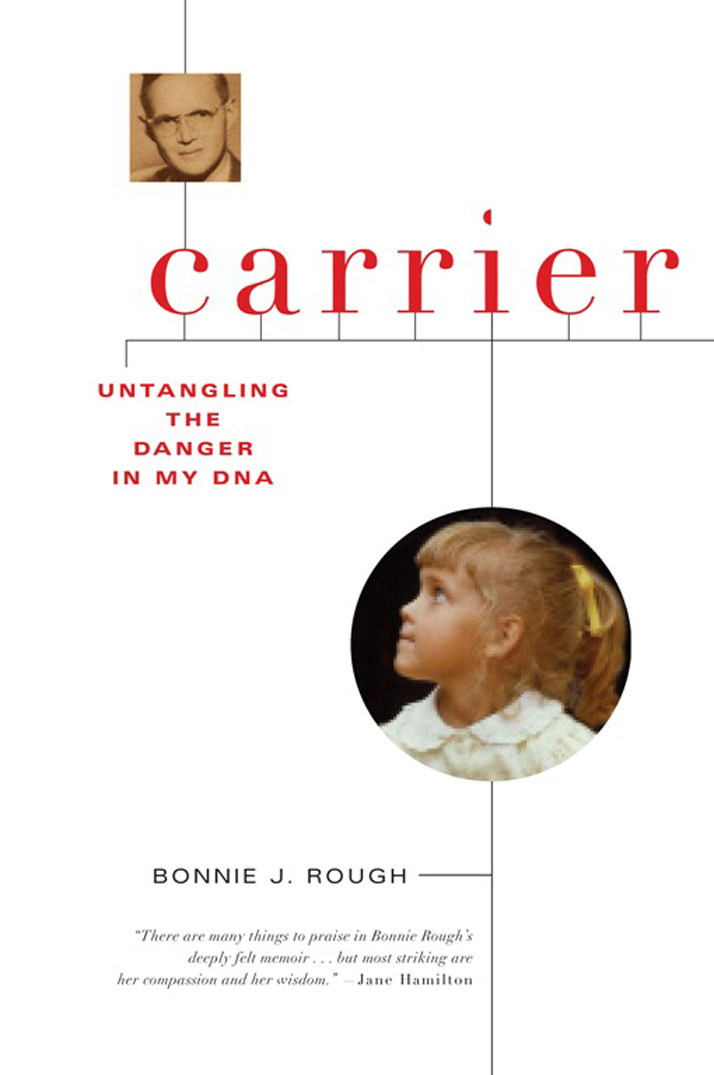

Earl, Esta, and Paula in Pueblo, Colorado, 1954

That Christmas Eve, I heard my mother go to Lukes bedside. We all knew how deeply my brother slumbered, but I imagined that some part of him must have heard her as she cried softly, Im sorry. Im so sorry.

The dinner dishes were done. The relatives gone. The wine-glasses empty. We children, grown, were snug in our beds. Dan and I had just turned out the light in the guest room. In the darkness, sounds were clear. My mothers crying on the other side of the wall reminded me of a night eighteen years earlier, when she had been pregnant with Luke. She had been napping in the afternoons late-autumn darkness, in the same Seattle house where we now slept. I sat at the kitchen table with my little sister, Amanda. Our father was fixing macaroni. We heard our mother scream.

Scrambling to her bedside, we found her sobbing Sorry, Im so sorry to the bump of her belly. I shouldnt have been afraid, she wailed as our father switched on the lamps. She said she had seen a yellow angel, three-dimensional like a laser projection, appearing at her side. The angel had seemed purposeful and peaceful as he passed both hands into my mothers belly, straight through walls of skin and muscle and womb. My mother showed us how the angel had rotated his wrists busily inside, fluttering his fingertips like a chef sprinkling something fine.

I didnt realize what he was doing. When I screamed, the angel turned blue and looked at me, just horrified. It was like he didnt know I was there. He stopped working and just disappeared. I scared him away.

Right then, I knew, my mother told me years later, that my baby would have what my dad had. And right then, I knew how she came to believe it was her fault.

When Luke was born, my parents asked the doctor to take a dental X-ray, just to rule out any problems. Later, the pediatrician poked his head into my parents hospital room and said simply, There are few tooth buds. My mother and father knew what this meant. A friend had brought a bottle of Champagne, and my father opened it. A nurse then wheeled into the room their pink-faced son with a head of dandelion fluff. My parents looked with love at my brother, who was very quiet and moved his lips with the concentration of an old man, then poured the Champagne. Toasting, they said together, Gods will be done. And they cried long into the night.

Eighteen years later, in 2004, my mothers tears still fell. The guilt of my foremothers haunted me. I had never understood my great-grandmother Josephines guilt about my grandfather Earlher eighth child, her baby boy, the chick she kept pulling sadly under her wing. What choice did she have, nearly a century ago? Though she had a brother with the disorder, how could she have known that those traits could appear in her children? Even if she had understood that the disorder was hereditary, could she have prevented a pregnancy if she hadnt wanted to run the risk? Could she have ended a pregnancy she sensed was going wrong? There they were, out on the parched Nebraska farm. The older children would soon leave, and only sisters would remain. Growing older and getting tired, my great-grandparents needed more sons. The snow blanketed and the dust rose and fell and the sunflowers opened and closed. My grandfather Earl, Josephines too-hot son, was her eighth child and last effort. No one blamed her for Earls condition, except perhaps her husband, whose back was breaking under all the work his son couldnt do. Little Earl knew, before he knew many things at all, that his mother felt guilty of something. I tried to imagine him going off to kindergarten, already old enough to know that his wisp of a body daily broke his mothers heart.