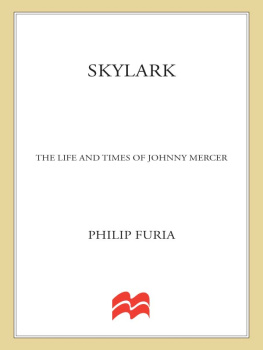

Also by GENE LEES

Leader of the Band: The Life of Woody Herman

You Cant Steal a Gift: Dizzy, Clark, Milt, and Nat

Cats of Any Color: Jazz, Black and White

The Modern Rhyming Dictionary: How to Write Lyrics

The Musical Worlds of Lerner and Loewe

Oscar Peterson: The Will to Swing

To Janet

Its quarter to three.

Theres no one in the place

except you and me,

So, set em up, Joe,

Ive got a little story

you oughta know.

Johnny Mercer

Acknowledgments

I owe much to many persons for help in the making of this book.

Howard S. (Howie) Richmond, whose TRO (The Richmond Organization) published many of Johns songs, as well as my own, was the first to urge me to undertake the project, and it was he who told me that John wanted me to do it. Johns daughter, Amanda Mercer Neder, also let me know that John wanted me to do it. Mandy opened the doors to the Mercer relatives for me.

The late Steve Allen, who did so many things well that it was often overlooked that he was a fine songwriter, was a major impetus. It saddens me that he did not live to see the book finished. Alan Bergman, who, with his wife, Marilyn, has written some of the loveliest lyrics of our time, also urged me to undertake the book.

I owe thanks to current and past members of the staff of the Pullen Library Special Collections section at Georgia State University, where many of Mercers papers repose, and especially to Charlene S. Hurt and Laura Botts.

Certain materials, including Johnnys letters to his wife, Ginger, and the quotations from his unpublished autobiography, are among the Johnny Mercer Papers, Popular Music Collection, Special Collections Department, University Library, copyright owned by Georgia State University, a unit of the Board of Regents of the University System of Georgia.

I thank the staff of the Georgia Historical Society in Savannah. Chuck Haddix of the University of Missouri-Kansas City provided material pertaining to the late Dave Dexter. My late friend Willis Conover did a superb interview with Mercer for his Voice of America program, Music USA. The tape of it is in the National Archives in College Park, Maryland.

In 2002, the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) did a four-part radio series titled Johnny Mercer: Accentuate the Positive, for which many of Johns associates, including me, were interviewed. The producer drew on past interviews with John and various of his colleagues, including Harry Warren and Hoagy Carmichael. This archive material is invaluable.

Johnny Mercer began an autobiography. After his death, his widow, Ginger, brought it to me. It was sporadic and fragmented, and its chronology was confused. She asked me whether I could edit it into some kind of coherence, which I did. A copy of my edited manuscript was left to Johnnys daughter, Amanda, and another remained in my hands. I have drawn on this manuscript. At times I wanted to keep the feeling of Johns vocabulary and flavor of speech. Where I have incorporated these passages into my text, they have been set in italics.

Over a period of years I interviewed Johnny several times, either for magazine articles or, in one instance, a program for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. I have drawn on these articles, and a tape of the CBC broadcast, and of course our many informal conversations.

The late Jimmy Hancock, a friend of Johns and nephew of one of the close friends of Johns youth, was my first guide to Savannah and the Mercer relatives. As I worked on the book, Jimmy left us, but he lived long enough to read and advise me on an early draft. I thank the late Jimmy McIntire and his wife, Barbara, and Johns niece, Libby Hammond.

I especially thank Rose Gilbert of Rancho Mirage, California, widow of Johns friend and fellow lyricist Wolfe Gilbert, and herself Johns friend of many years.

John was often in my conversations with his friends and professional colleagues, among them Johnny Mandel, David Raksin, the late Henry Mancini, and the late Les Brown. Though I did not foresee using this material, these conversations were valuable indeed. I especially cite my gratitude to the late Peggy Lee; the late Jay Livingston; the late Paul Weston and his widow, Jo Stafford; the late Harry Warren; and the late Harold Arlen.

And I especially thank Nancy Keith Gerard, for reasons that will become abundantly clear.

For reading the manuscript in whole or in part, I thank Nancy; my wife, Janet; Jo Stafford; Mickey Goldsen; Howie Richmond; Rose Gilbert; Mandy Mercer Neder; the late Jimmy Hancock; and Phil and Jill Woods.

Formally or informally, I interviewed over a period of years Steve Allen, Jean Bach, Betty Bennett, Alan and Marilyn Bergman, Oscar Brand, Les Brown, Bob Corwin, James Corwin, John Corwin, Ray Evans, Nancy Keith Gerard, Rose Gilbert, Mickey Goldsen, Bill Goodwin, Jill Goodwin, Jimmy Hancock, William Harbach, Dwight Hemion, Gilbert Keith, Alan Livingston, Jay Livingston, James T. Maher, Nick Mamalakis, Henry Mancini, Jeff Mercer, Amanda Mercer Neder, David Oppenheim, Howie Richmond, Andr Previn, Arthur Schwartz, Carl Sigman, Harry Warren, Jo Stafford Weston, Paul Weston, and Margaret Whiting. I interviewed one of Johns physicians, Dr. Michael R. Kadin, who treated him after his surgery. I gained insight into his condition from interviews with three neurologists: Dr. Barry Little, radio neurologist Romo thier, and neurosurgeon Albert MacDade.

I thank Matthew Haskins, lecturer in the American Studies Department at California State University, Fullerton, for providing me with a complete set of copies of The Capitol News from March 1943 to December 1951.

I am not enamored of footnotes, and so I have identified the sources of quotations in the text itself. Wherever there is a quotation without attribution, the comments were made to me.

Johnnys friends tended to call him John. He signed his letters to his mother John, Johnny, once or twice Jawnnny, and occasionally Bubba. I think Johnny was the public figure, but John was the private friend. Both names are used throughout the book.

One

It is often difficult to remember exactly where and when you met someone, but in the case of Johnny Mercer I remember that first encounter almost to the minute. I had come out to Los Angeles from New York, where I then lived, to write the lyrics for some songs in a movie. I called a friend, the wonderful singer Betty Bennett, and asked if she might be free for dinner that night. She said she would be attending a birthday party, and then added, Do you want to go with me? I asked her whose birthday it was and she said it was that of the composer John Williams.

I said, Since today is also my birthday, Id love to go.

We went to the Williams house. As we entered, I saw three men standing at the top of a little stairway from the foyer into the living room. The one on the left was a friend of several years, Henry Mancini. The one on the right I did not recognize, although I soon learned he was Dave Cavanaugh, one of the most important producers at Capitol Records. The one in the middle, the man with a space between his incisors when he smiled, was Johnny Mercer. I knew that face from countless photographs in Down Beat and other publications, including one called The Capitol News, which was distributed free through record stores throughout the United States. And because it was my thirty-eighth birthday, and John Williamss thirty-fifth, I can date this meeting exactly: February 8, 1966, shortly after eight p.m.