On the morning of July 18, 1868, a train carrying the most famous man in America pulled into the frontier town of Manhattan, Kansas. General Ulysses S. Grant was on board. Three years earlier he had led the Union Army to victory in the Civil War. Now he was running for President. All across the northern United States, people gathered to cheer on their hero. At each stop Grant would step out of his private railroad car and bow to his adoring fans. Then he would retreat into his car, and the train would move on to the next stop on the tour.

As the train pulled slowly into Manhattan, an enthusiastic crowd began chanting, Grant! Grant! Grant! The general stepped onto the platform, doffed his hat, and bowed. People were close enough to reach out and touch him, but no one dared approach the larger-than-life Grant. And the general was not the kind of back-slapping, hand-shaking politician who wades into a crowd of supporters.

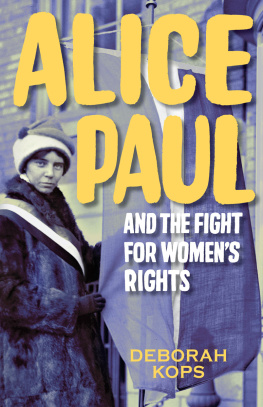

When General Ulysses S. Grant (shown here in an 1865 photo) decided to run for president in 1868, he was a celebrated war hero. He was quiet and aloof, but presidential candidates in those days were not expected to make speeches.

Just then, a tall, plain-looking woman began making her way through the cheering crowd. With one hand she clutched her long, full skirts. With the other, she parted the crowd. Halfway across she caught the generals eye. He gave her a friendly nod. When she reached Grant, the woman thrust out her hand.

General, she announced, as one of the mothers of Kansas, I bid you welcome!

Before the celebrated war hero could reply, she had another message for him, also from the mothers of Kansas.

If we could vote, she said, we would vote for Grant!

His craggy face broke into a broad smile. You can electioneer for us, he said, pumping her hand.

Aye, aye, she said in her unmistakable New England accent. That we can.

The ice was broken, and the men in the crowd surged forward. Everyone was now eager to shake Grants hand. When the train started up a few minutes later, it left behind a sea of outstretched hands.

Later, a friend who witnessed this scene came up to the outspoken woman.

You were acquainted with him in Washington? he asked. I thought from the way his face lighted up that you had met before. Clarina Nichols smiled and shook her head no. This was the first time she had met General Grant. She had merely seen him

being stared at like an elephant and decided to put him at ease. While she was at it, she would deliver a good-humored message about woman suffrage, the right to vote. After all, opportunities like this did not come along every day, especially in a state so far away from the centers of power and influence.

Few 19th-century Americans spoke up for women as often as Clarina Nichols did. Her beliefs led her halfway across the country to Kansas. And on that summer day in 1868, they gave her the nerve to approach the man who would become the next President of the United States.

How she would have relished a one-on-one talk with Grant. He knew that women were not allowed to vote, but he probably gave it little thought. Like most people he accepted the notion of separate spheres for men and women. He probably also believed that the God-given role of man was to rule over the socalled weaker sex. The result of this kind of thinking was a system of laws that favored men and discriminated against women in many ways.

Women could not hold public office or serve on juries. Public universities were closed to them. All the higher paying trades and professions shut out females. In cases of divorce, if the husband wanted custody of the children, it was granted. When a husband died without a will, his wife inherited just one-third of his estate; the rest was given to the husbands male relatives. Whatever money a married woman earned through her own hard work did not legally belong to her, but could be spent by her husband in any way he chose. And so on. The list of mens rights, and womens wrongs, was very lengthy in 1868.

For more than 20 years, however, women had been challenging these laws and the thinking behind the laws. These women, and the men who supported them, had formed a movement the worlds first womens rights movement. Few women had meant more to that movement than Clarina Nichols. In person, in public, and in print, Nichols had already devoted half her life to opening minds and breaking down prejudices. Her efforts had helped women gain rights in several states and had brought one state into the national spotlight. And her quest for equal rights did not stop there. When slavery threatened to move into the unsettled territories of the country, she uprooted her family in the East to join the freedom fighters in the West.

Toward the end of her life she was featured in a popular book that profiled the 100 most important women of the 19th century. But then the life and achievements of Clarina Nichols began to slip through the cracks of history. Though she had written thousands of articles for newspapers, she had never kept a diary, and she never wrote a book about her life. Over time her papers were scattered and lost as she moved around the country.

Some of her writings, though, found their way into libraries and museums from Vermont to California. Family members, friends, and historians worked hard to preserve her memory. Gathered together, the remaining pieces of her life letters, newspaper articles, poems, speeches, drawings, photographs tell an amazing story. Clarina Nichols was both an unsung hero and one part of an unsung multitude of women who spoke up, acted up, demanded their rights, and changed the world.