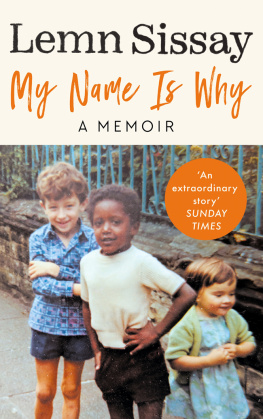

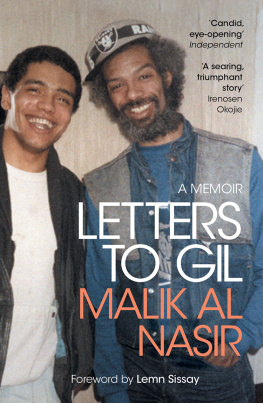

Also by Lemn Sissay

Poetry

Perceptions of the Pen

Tender Fingers in a Clenched Fist

The Fire People (ed.)

Morning Breaks in the Elevator

Rebel Without Applause

The Emperors Watchmaker

Listener

Gold from the Stone

Drama

Skeletons in the Cupboard

Dont Look Down

Chaos by Design

Storm

Something Dark

Why I Dont Hate White People

Refugee Boy

First published in Great Britain, the USA and Canada in 2019

by Canongate Books Ltd, 14 High Street, Edinburgh EH1 1TE

Distributed in the USA by Publishers Group West

and in Canada by Publishers Group Canada

canongate.co.uk

This digital edition first published in 2019 by Canongate Books

Copyright Lemn Sissay, 2019

The right of Lemn Sissay to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the

Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

Excerpt from Ride Natty Ride, written by Bob Marley.

Published by Fifty Six Hope Road Music Ltd/Primary Wave/

Blue Mountain.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available on

request from the British Library

ISBN 978 1 78689 234 8

eISBN 978 1 78689 235 5

For

Yemarshet, Tsahaiwork, Teguest, Mehatem,

Giday, Abiyu, Mimi, Wuleta,

Catherine, David, Christopher, Sarah and Helen

The two most important days in your life are the day you are born and the day you find out why

Anon., attributed to Mark Twain

I am the bull in the china shop

With all my strength and will

As a storm smashed the teacups

I stood still

CONTENTS

PREFACE

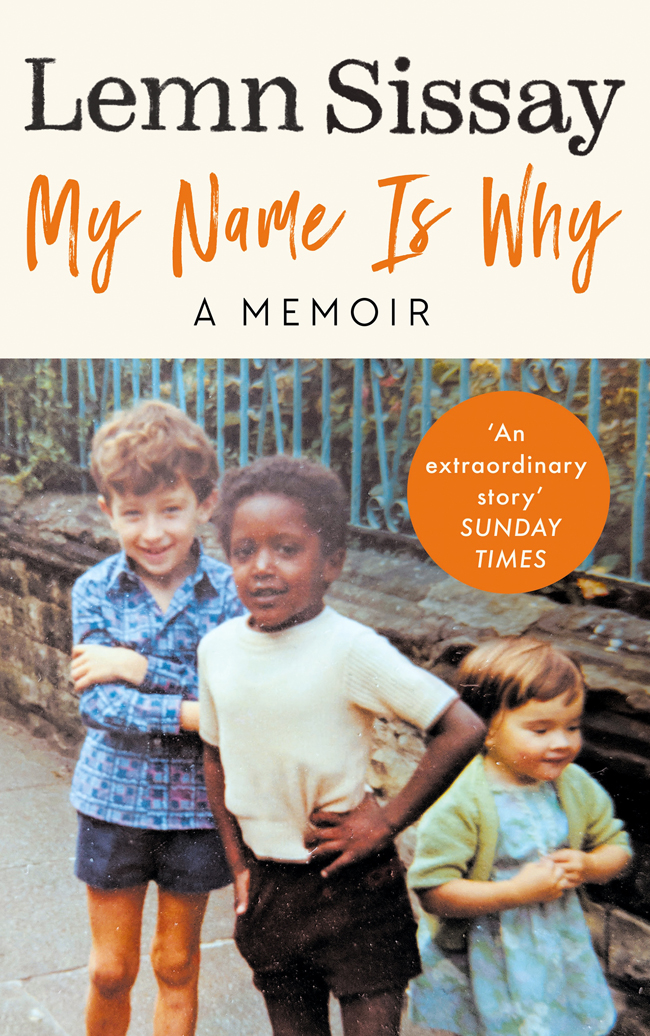

A t fourteen I tattooed the initials of what I thought was my name into my hand. The tattoo is still there but it wasnt my name. Its a reminder that Ive been somewhere I should never have been. I was not who I thought I was. The Authority knew it but I didnt.

The Authority had been writing reports about me from the day I was born. My first footsteps were followed by the click clack clack of a typewriter: The boy is walking. My first words were recorded, click clack clack: The boy has learned to talk. Fingers were poised above a typewriter waiting for whatever happened next: The boy is adapting.

Paper zipped from typewriters and into files. The files slipped into folders under the S section of a tall metal filing cabinet. For eighteen years this process repeated over and over again. Click clack clack. Secret meetings were held. The folders were taken out and placed on tables surrounded by men and women from The Authority. Decisions were made: Put him here, move him there. Shall we try drugs? Try this, try that. After eighteen years of experimentation The Authority threw me out. It locked the doors securely behind me and hid the files in a data company called The Iron Mountain.

So I wrote to The Authority and hand-delivered the letter. The reply informed me I had to write to Customer Services. I wrote to Customer Services. Customer Services replied to say they were not permitted to release the files. The Authority placed me with incapable foster parents. It imprisoned me. It moved me from institution to institution. And yet now, at eighteen years old, I had no history, no witnesses, no family.

In 2015, following a thirty-year campaign to get my records, the Chief Executive of Wigan Council, Donna Hall, wrote me a letter. She had them. Within a few months I received four thick folders of documents marked A, B, C and D. Click clack clack. On reading them, I knew.

I took The Authority to court.

How does a government steal a child and then imprison him? How does it keep it a secret? This story is how. It is for my brothers and sisters on my mothers side and my fathers side. This is for my mother and father and my aunts and uncles and for Ethiopians.

CHAPTER 1

Awake among the lost and found

The files left on the open floor

The frozen leaves on frosted ground

The frosted keys in a frozen door

E ighteen years of records written by strangers. All the answers to all my questions were here. Possibly. And yet, I feared what theyd reveal about me or what theyd reveal about the people who were entrusted with my care. What truths or untruths? Maybe I was loved. Maybe my mother didnt want me. Maybe it was all my fault. Maybe the bath taps in the bathroom were not electrified. Maybe that was false memory syndrome.

A friend burned her files when she received them from The Authority. Another cant look at hers to this day. Ill start by simply recording my reactions to the first early documents and well see how this unfolds.

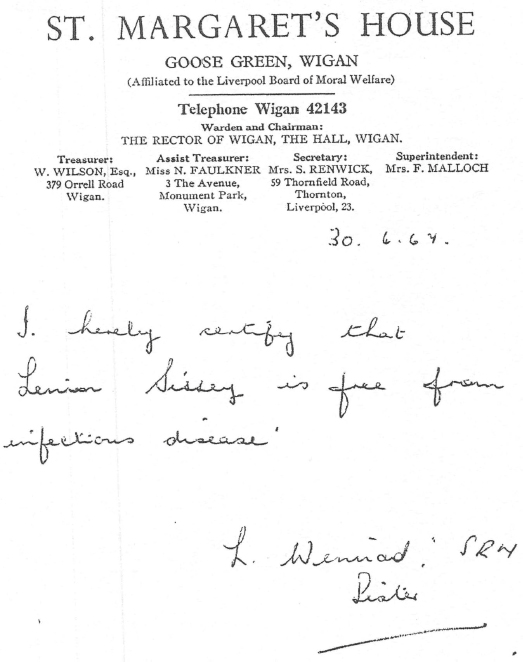

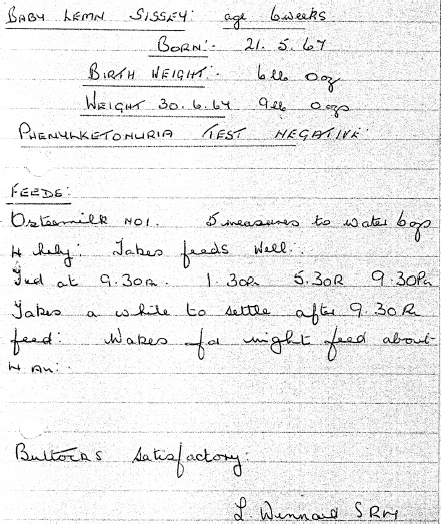

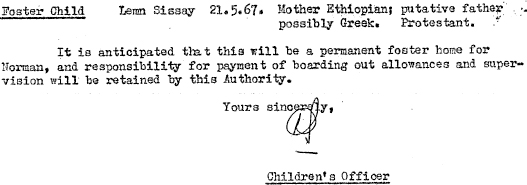

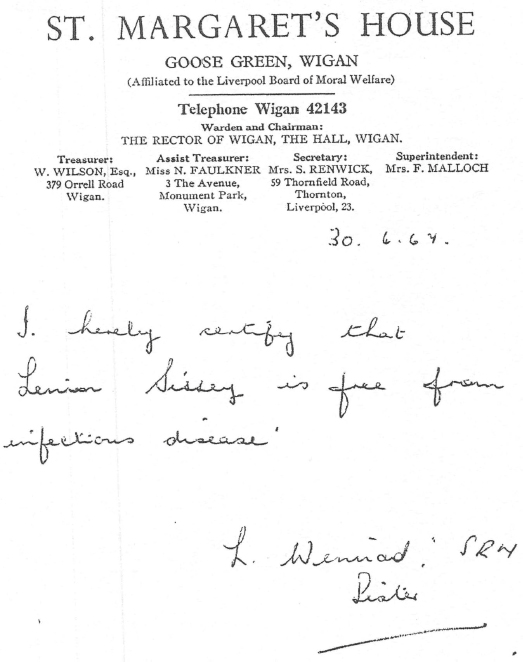

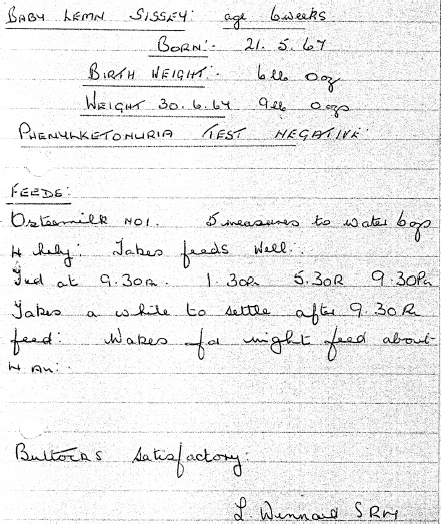

St Margarets House was an institution for unmarried mothers affiliated to the Liverpool Board of Moral Welfare. On 30 June 1967, State Registered Nurse L. Winnard wrote that Lemion Sissey (misspelt) was free from infectious disease. In a second note on the same day she recorded that the six-week-old baby now Lemn Sissey? weighed nine pounds.

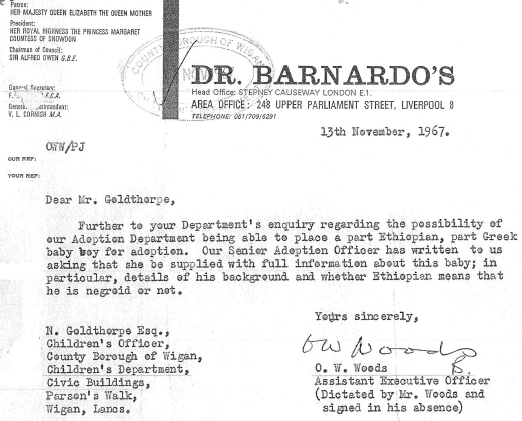

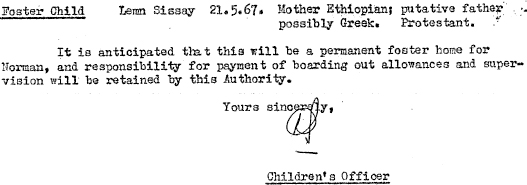

In the letter below Im six months old. At this point my mother is invisible.

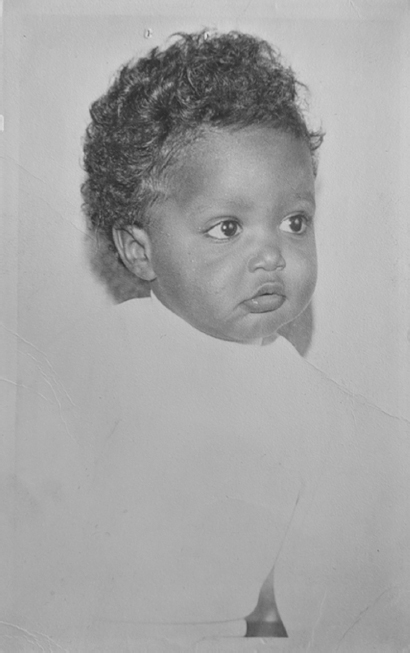

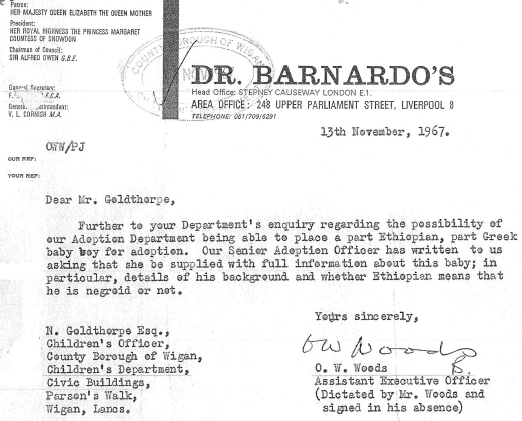

And then there was this:

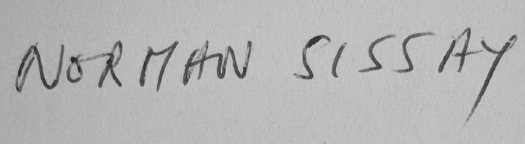

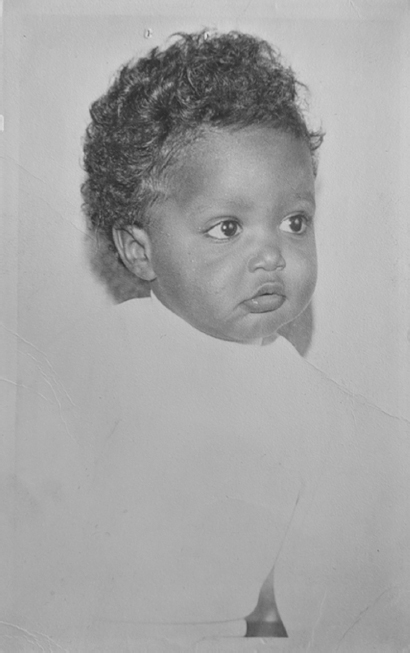

On the back of the photo it says:

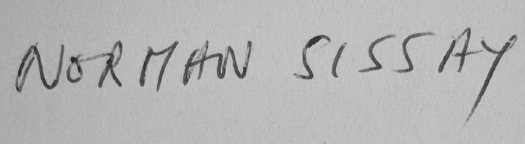

So my name has changed to Norman Sissay; I am supposed to be part Greek. An adoption agency asks whether Ethiopian means he is negroid or not. This is the first time I have seen myself referred to as Norman Sissay.

When the letter from which this extract is taken was written, I was almost eight months old. In England unmarried pregnant women or girls were placed in Mother and Baby homes like St Margarets with the sole aim of harvesting their children, then the women were shipped back home to say they had been away on a little break. A little break. They were barely adults themselves. Many of them didnt understand the full implication of the word adoption. They were sent home without their newborns after signing the adoption papers. They must have been bewildered and in shock at the loss of their first child. I found testaments online from people who lived near to St Margarets.

It was very eerie in certain parts it really felt haunted.

I can remember being in the Billinge Maternity unit when one of the young girls from St Margarets had her baby. The only visitor was a lady social worker and on the day mum and baby were due to leave, mum was taken away in one car (crying) and baby hurried away in another!

![Johnson - This boy: [a memoir of a childhood]](/uploads/posts/book/185323/thumbs/johnson-this-boy-a-memoir-of-a-childhood.jpg)