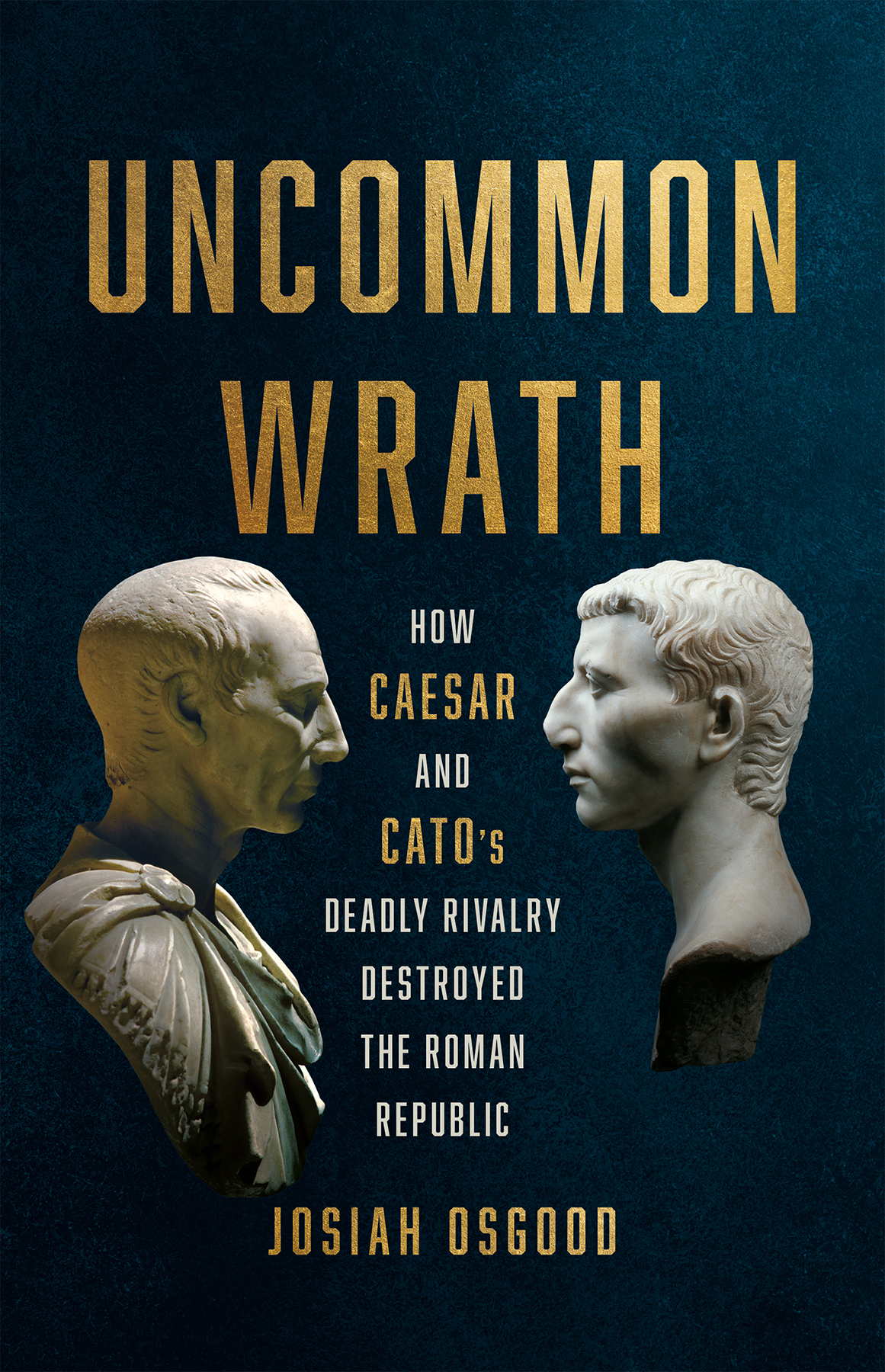

Copyright 2022 by Josiah Osgood

Cover design by Chin-Yee Lai

Cover images Scala / Art Resource, NY; robertharding / Alamy Stock Photo; detchana wangkheeree / Shutterstock.com; nadianb / Shutterstock.com

Cover copyright 2022 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Basic Books

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

www.basicbooks.com

First Edition: November 2022

Published by Basic Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Basic Books name and logo is a trademark of the Hachette Book Group.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2022940722

ISBNs: 9781541620117 (hardcover), 9781541620100 (ebook)

E3-20220928-JV-NF-ORI

Explore book giveaways, sneak peeks, deals, and more.

Tap here to learn more.

A S THE SUN ROSE OVER R OME ON D ECEMBER , 63 BC, THE consul Marcus Tullius Cicero summoned the five conspirators. Just hours before, Cicero had completed a sting operation through which he had obtained letters that clearly implicated the men in a plot to overthrow the government. He also sent an official to confiscate weapons from one of their houses. There the official found a huge quantity of swords and daggers, all newly sharpened. It was time for the conspirators to answer for themselves before the Senate.

One of the five could not be found, but the other four obeyed Ciceros summons. He put them under guard and took them to the Temple of Concord, where the Senate was meeting that day. One by one Cicero interrogated them in front of all the assembled senators. The man at whose house the swords and daggers had been foundhimself a senatorclaimed that he was merely a collector of fine weapons. Still, as Cicero brought out the letters, unsealed them, and read them aloud, none of the men tried to deny what was clear to everyone: they were in league with Lucius Catiline.

Catiline was a politician with bitter grievances. Though he belonged to one of Romes oldest families, earlier that year he had, for a second time, failed to win election to the top office of consul, held annually by two men. He was on the verge of bankruptcy and could not afford to wait and try again the next year. In early November, he fled Rome and assumed command of an armed uprising in northern Italy. The five conspirators left behind within the city walls were under orders to prepare the way for Catilines return by assassinating leading political figures and torching parts of Rome.

An army was already on its way to confront Catiline, but the Senate now had to decide what to do with the men under arrest. They reassembled two days after the interrogation to settle on a plan. As members of the body stood up in succession to state their views, two proposals gained favor. One was to put the conspirators to death at once. Not only would this protect the city from efforts underway to rescue the detainees; it would scare off wavering supporters from throwing in with Catiline. The other scheme was to imprison the conspirators for life in the towns of Italy and to confiscate their property. The advantage of this plan was that it recognized the heinousness of the conspirators actions while also acknowledging the right enjoyed by even the humblest Roman citizen not to be executed without a trial.

It was Julius Caesar who put forward the second proposal. Though a member of one of Romes ancient patrician families, the thirty-seven-year-old senator had built his political career by championing the interests of the people. He believed he had much to gain if he stood up for citizens rights while still taking a firm stance against the conspirators. As more senators spoke after Caesar, it seemed as if his view was going to prevail. But then the debate unexpectedly took a turn.

Marcus Porcius Cato, a recent addition to the Senate and five years younger than Caesar, rose and gave what proved to be the speech of his life.

Wake up, before it is too late, Cato told the senators. We are surrounded on all sides. Catiline and his army press at our throats. There are other enemies within the walls and even in the heart of our city.

There was only one choice. The conspirators had already confessed their guilt. And so in accordance with ancestral practice, they should be executed at once.

As Cato finished speaking and sat back down, the senators broke into applause. Many stood up to say they agreed with Cato. Cicero called for a vote, and Catos motion passed overwhelmingly. Caesars proposal had been crushed.

The words just quoted from Catos speech come not from a direct transcriptone was made at the time but has not survivedbut rather from a historical work written about two decades later: The War Against Catiline of Gaius Sallustius Crispus (Sallust, in English), a senator who had served as an officer under Julius Caesar but then withdrew from public life.December of 63 BC. Caesar was already a major political figure. Now Cato was too.

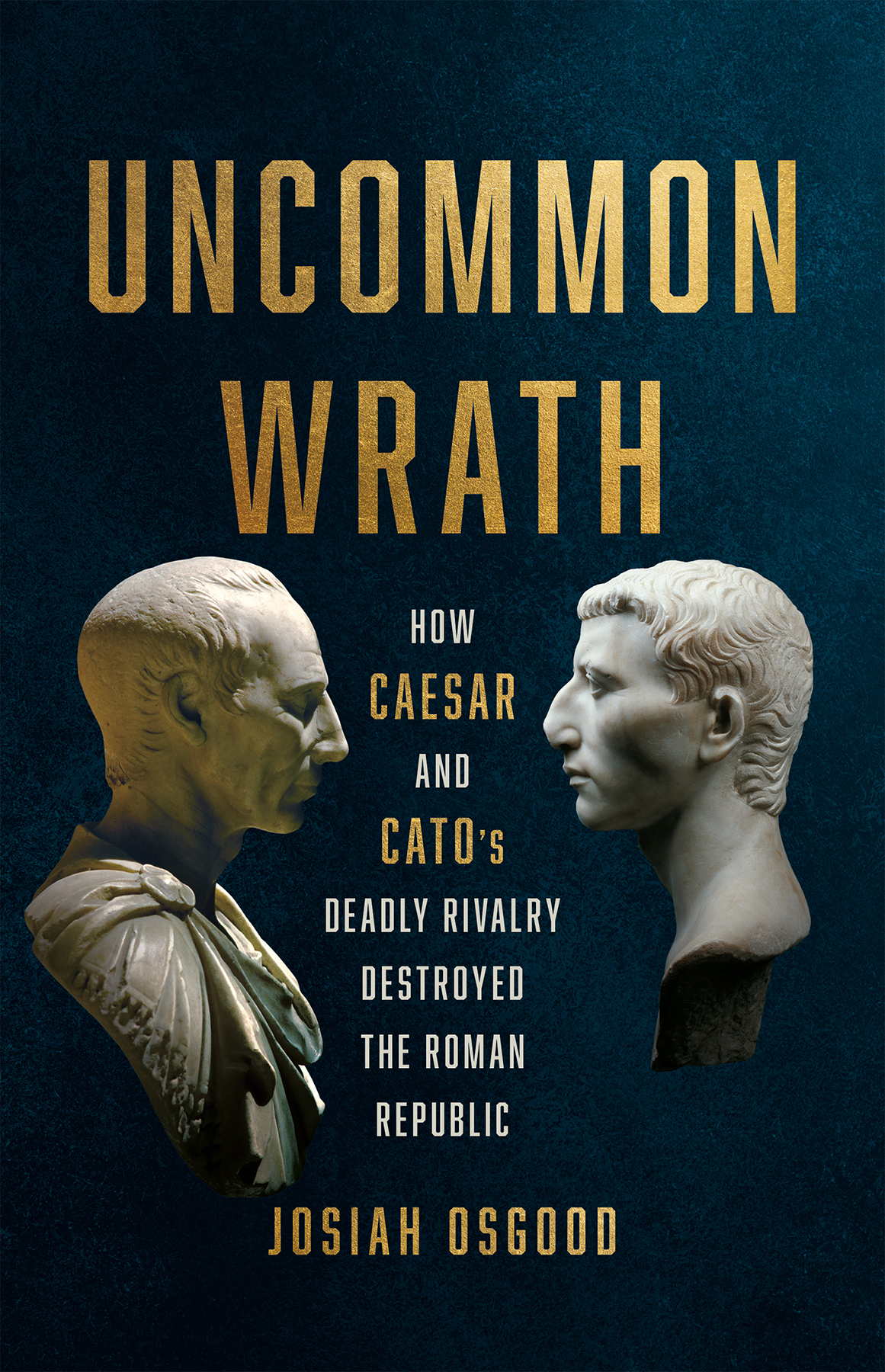

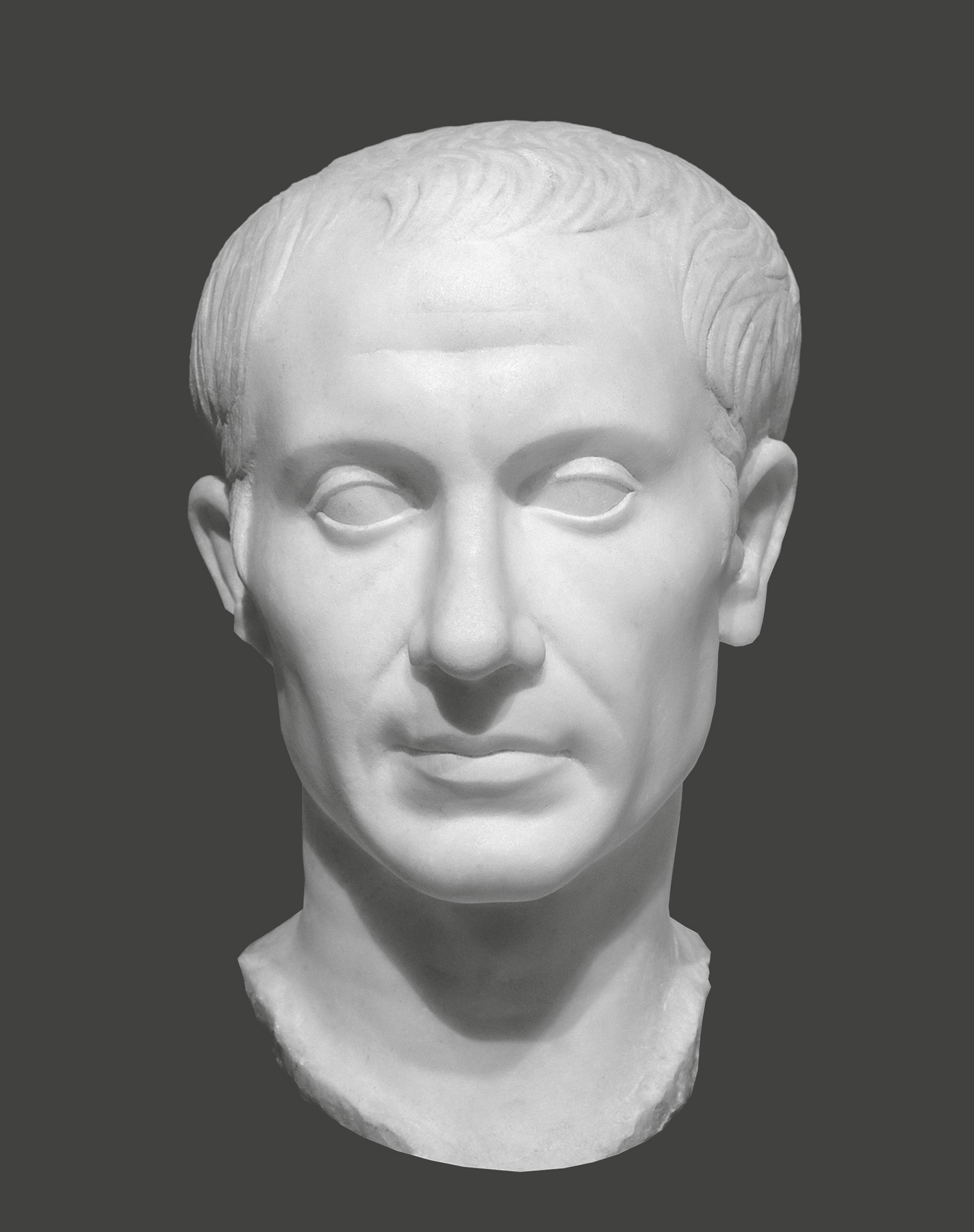

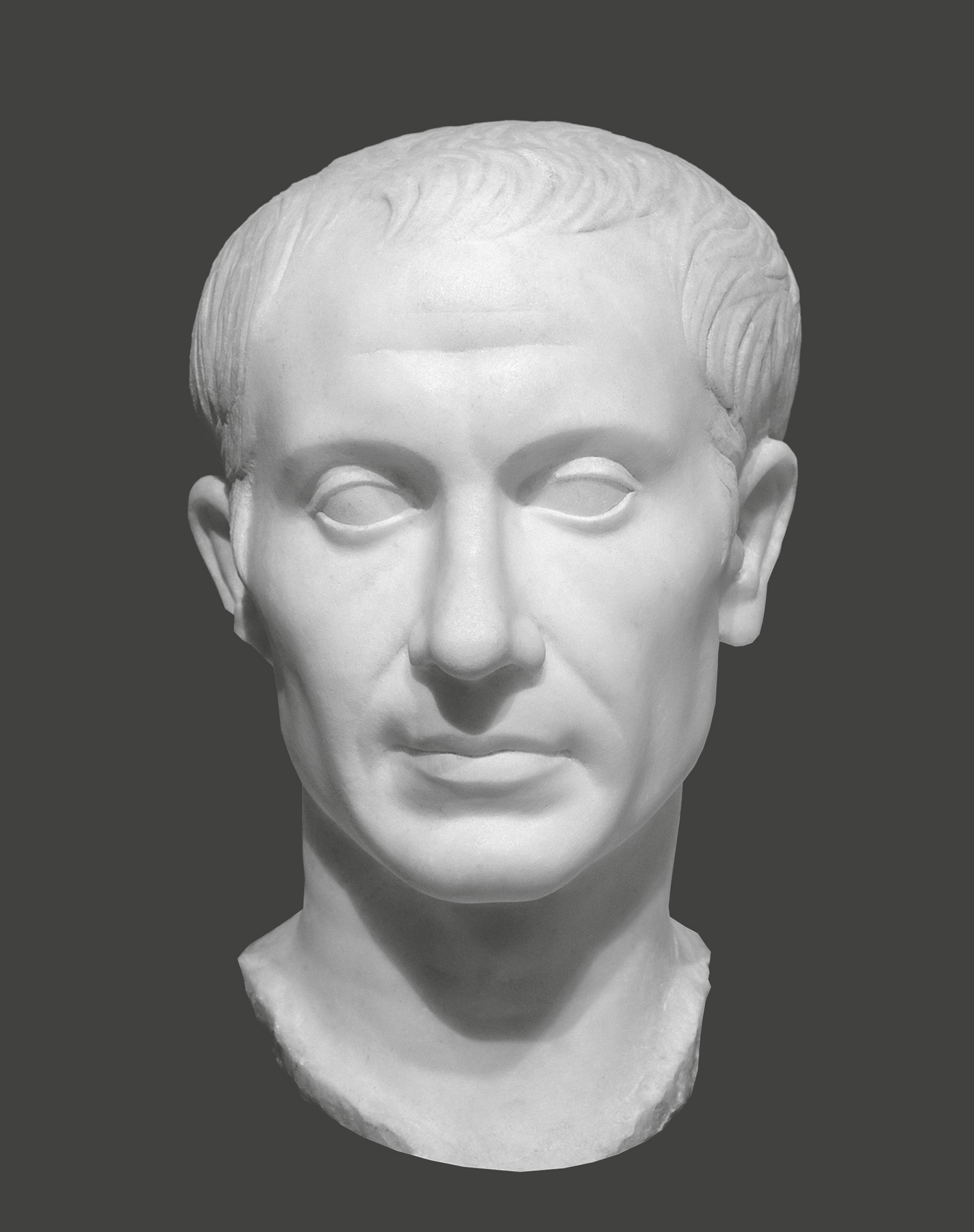

A posthumous portrait of Caesar discovered on the island of Pantelleria in 2003.

Credit: akg-images

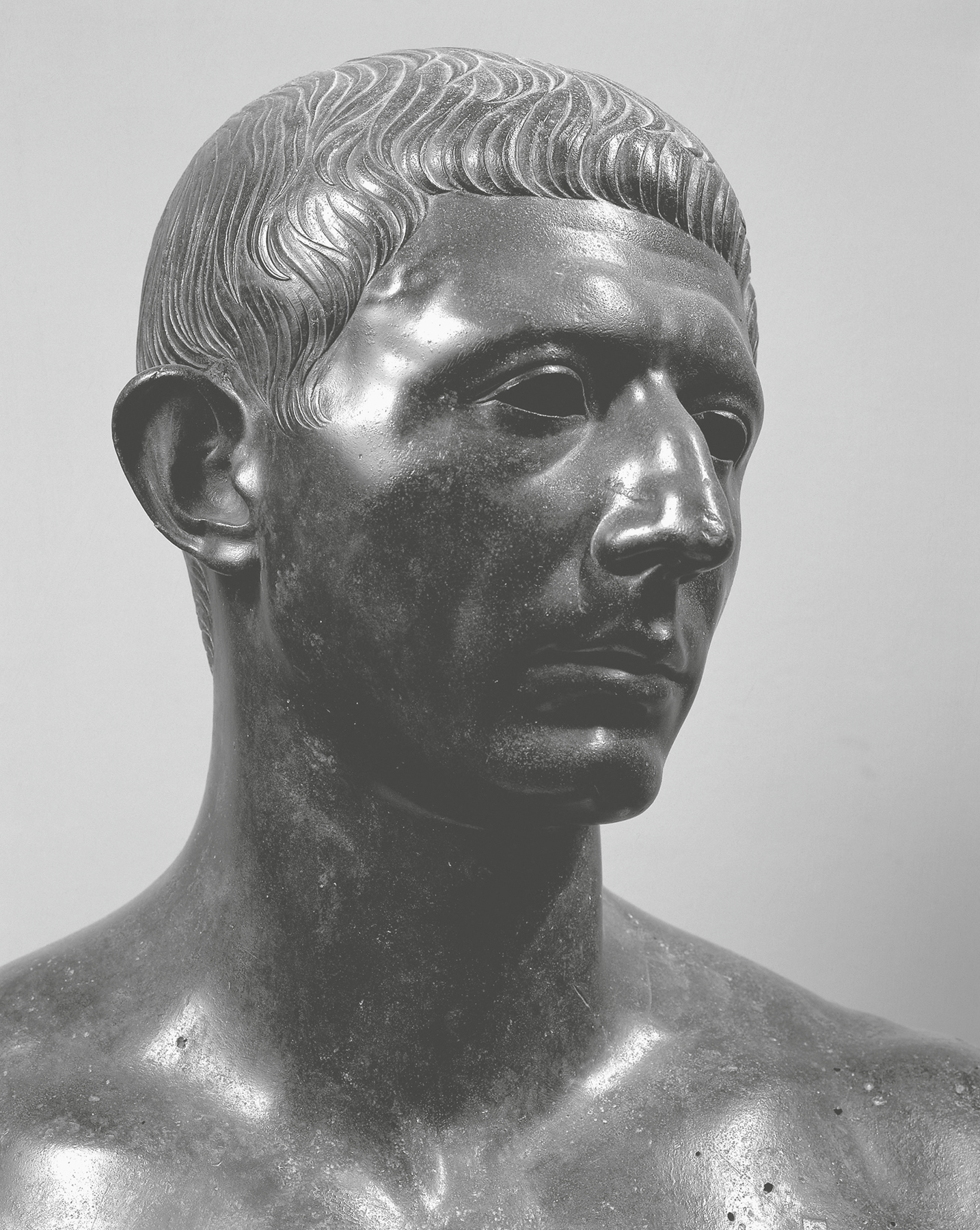

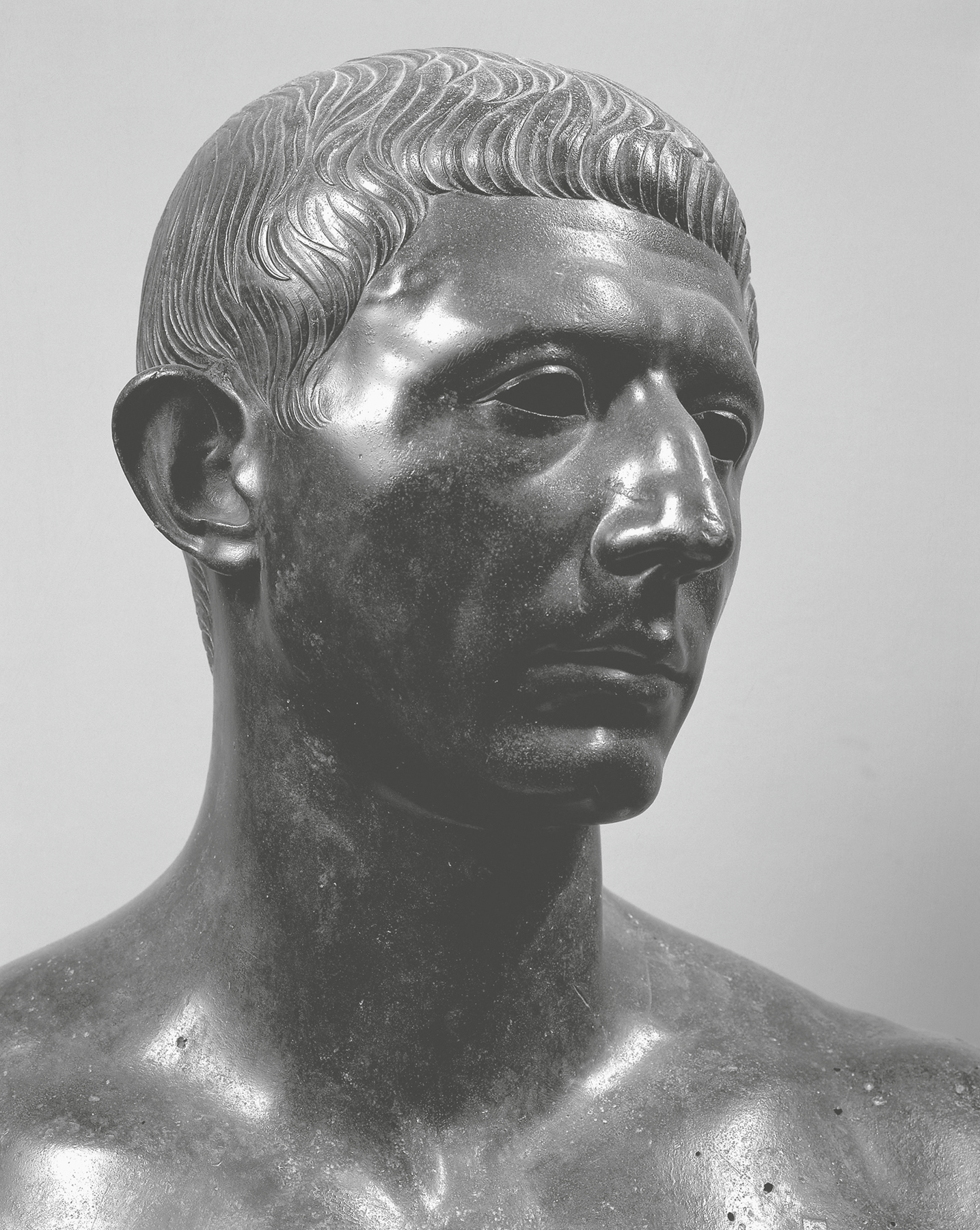

A posthumous portrait of Cato discovered in Volubilis (Morocco) in the 1940s.

Credit: G. Dagli Orti / NPLDeA Picture Library/Bridgeman Images

Surprising as Catos triumph over Caesar is, even more unexpected is the reflection Sallust then offers. Reading and listening about the many splendid deeds that the Roman people have done at home and on campaign, by land and by sea, a desire came over me to examine what it was in particular that allowed such great undertakings, he writes. As he considered the matter, it grew clearer to him that the excellence of a few citizens was what had made all the successes of earlier days possible. But with greater power came wealth, and wealth corrupted the citizenry. Romans grew lazy. As if worn out from giving birth, for many stretches of time Rome went without producing a single man distinguished by excellence.

The age of Catiline was an age in which virtually everyone in public life was bent on trying to capture the Republic for himselfbut for Sallust there were still two men of extraordinary excellence: Cato and Caesar. And since they have appeared in my story, I am resolved not to pass them over in silence, but to describe, to the extent of my ability, the nature and character of each.