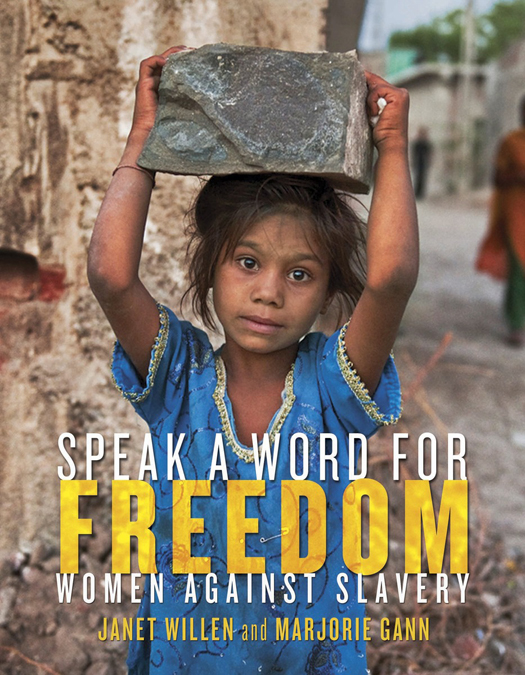

Copyright 2015 by Janet Willen and Marjorie Gann

Published in Canada and the United States of America by Tundra Books, a division of Random House of Canada Limited, a Penguin Random House Company

Library of Congress Control Number: 2014939465

All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or stored in a retrieval system, without the prior written consent of the publisheror, in case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agencyis an infringement of the copyright law.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Willen, Janet, author

Speak a word for freedom : women against slavery / by Janet

Willen and Marjorie Gann.

ISBN 978-1-77049-651-4 (bound).ISBN 978-1-77049-653-8 (epub)

1. Women abolitionistsBiographyJuvenile literature.

2. SlaveryJuvenile literature. I. Gann, Marjorie, author II. Title.

HT1029.A3W54 2015 j326.80922 C2014-902487-8

C2014-902488-6

Edited by Sue Tate

Designed by Leah Springate

www.penguinrandomhouse.ca

v3.1

To our husbands, Mark Willen and Andrew Gann

AUTHORS NOTE

In telling the stories of people who have fought against slavery, we describe different types of enslavement. By slavery, we mean the absolute control of one person by another. We occasionally refer to slaves who were sent by their masters to work for others under a financial arrangement, with the slave paying a specified amount to the master and keeping any money left over. Even though money changed hands, this system is just as much slavery as any other because the slave is still deprived of the freedom to marry, live where he or she chooses, leave one job for another and so on.

Our research led us to historical documents in books and archives and on the Internet. Those earlier writings often use spelling, punctuation and capitalization we no longer use today. We kept the original except where slight changes would make the historical material easier to read. Some quotations from the past include words that are dated or offensive to us today. Obnoxious as these are, they reflect the racial prejudices that underpinned slavery, and we believe they are part of the story we have to tell.

We used many primary sources for Harriet Tubmans stories. Each of Tubmans scribes had a different way of recording her speech. In quoting her, we have tried to retain the flavor of her language while smoothing out the dialect to make it easier to understand.

CONTENTS

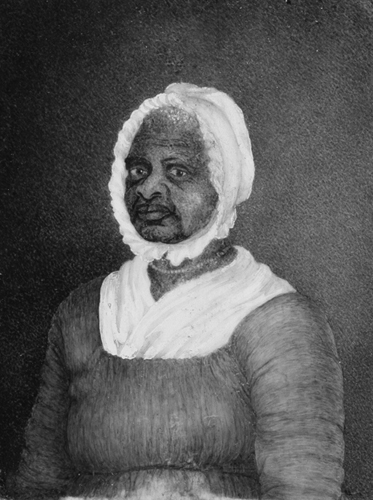

Elizabeth Freeman is wearing a necklace of gold beads that she later gave to Catharine Sedgwick, the writer who told her story in Slavery in New England.

I T WAS AN UNUSUAL SIGHT IN THE COURTROOM in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, on August 21, 1781. White people usually confronted other white people at trial, but on that day two black slaves, a woman called Mum Bett and a man known only as Brom, appeared with their white lawyer, Theodore Sedgwick, in a lawsuit against their owner. The case, known as Brom & Bett v. J. Ashley, stated that Brom, a Negro Man, and Bett, a Negro Woman, opposed John Ashley, their owner. The suit did not dignify Brom or Bett with a last name.

Broms full name and life story have been lost to history, but we know a lot about Bett from Sedgwick family lore. As a young slave she was known as Betty and then later as Mammy Bett, Mumbet or Mum Bett. Bett married, but there is no record of her husbands name. He died fighting in the American Revolution, leaving her with a young child. Bett took the name Elizabeth Freeman following her court case.

Before the trial, Freeman was a slave in the house of John Ashley, a prominent and widely respected white lawyer. Though Freemans master was kind, his wife was cruel. The mistress once lifted an iron kitchen shovel, still hot from cleaning the oven, and aimed it at Freemans sister, Lizzy, a sickly and timid young woman. Freeman did the only thing she could: she jumped in the way to shield the girl and took the blow herself. The shovel cut through Freemans arm to her bone, burning her and leaving her scarred for life. Freeman often spoke of the incident to Sedgwicks children, and two of them, his daughter Catharine Maria and son Theodore Jr., wrote about it.

I had a bad arm all winter, but Madam had the worst of it, Freeman later told Catharine Sedgwick. Freeman made a point of leaving her arm uncovered when she was with her mistress so people would ask what happened. Ask missis! she would reply, taking the opportunity to shame the woman who had injured her. The mistress never tried to strike her sister again.

More than anything, Freeman wanted her liberty. Any time, any time while I was a slave, if one minutes freedom had been offered to me, and I had been told I must die at the end of that minute, I would have taken itjust to stand one minute on Gods earth a free woman, she told Catharine Sedgwick. One day Freeman heard a reading of the Declaration of Independence, the statement by American colonists that they were breaking free of Britain. Its now famous words all men are created equal gave her an idea.

She had overheard Theodore Sedgwick talking with her master on his occasional visits to the Ashley house. Their conversations convinced her that Sedgwick believed that all people were created equal and free. The day after she heard the Declaration of Independence read, she went to his office, told him she was not a dumb critter, and asked if the law would give her her freedom. Sedgwick agreed to take her case.

Before an all-male, all-white jury, Ashleys lawyers reasoned that Bett and Brom, as they were known during the trial, were Ashleys legal Negro servants, by which they meant slaves. Sedgwick disagreed. He declared that there was no law establishing slavery and that the new Massachusetts state constitution, adopted just the year before, in 1780, made slavery illegal because it said all people were born free and equal.

The jury agreed with Sedgwick, declared Bett and Brom free, and ordered Ashley to pay damages and court costs. Once free, Elizabeth Freeman went to work for her lawyers family in a role Catharine Sedgwick described as a kind of governess. In her later years Freeman worked for other families as well, and by her extreme industry and economy, her lawyers son Theodore Jr. wrote, she supported a large family of grand-children and great-grand-children.

Freeman is the only person not related to the Sedgwick family to be buried in the family plot in Massachusetts. Her epitaph reads:

ELIZABETH FREEMAN

known by the name of MUMBET

died Dec. 28, 1829.

Her supposed age was 85 years.