That time is past,

And all its aching joys are now no more,

And all its dizzy raptures. Not for this

Faint I, nor mourn nor murmur, other gifts

Have followed; for such loss, I would believe,

Abundant recompence. For I have learned

To look on nature, not as in the hour

Of thoughtless youth; but hearing oftentimes

The still, sad music of humanity,

Nor harsh nor grating, though of ample power

To chasten and subdue. And I have felt

A presence that disturbs me with the joy

Of elevated thoughts; a sense sublime

Of something far more deeply interfused,

Whose dwelling is the light of setting suns,

And the round ocean and the living air,

And the blue sky, and in the mind of man;

A motion and a spirit, that impels

All thinking things, all objects of all thought,

And rolls through all things.

from William Wordsworth, Lines Composed a Few Miles Above Tintern Abbey, On Revisiting the Banks of the Wye During a Tour, July 13, 1798

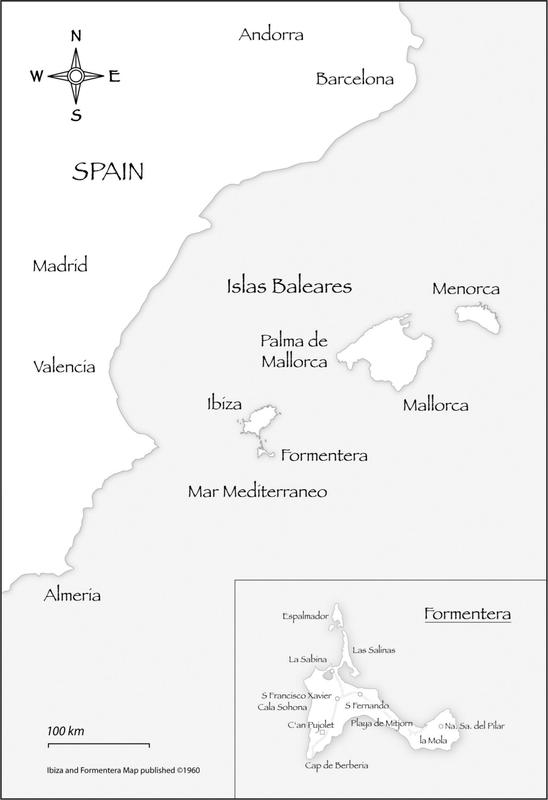

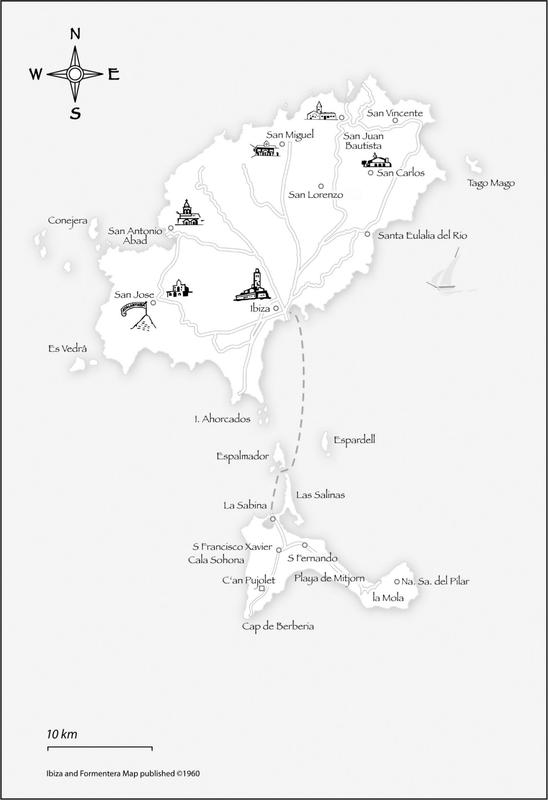

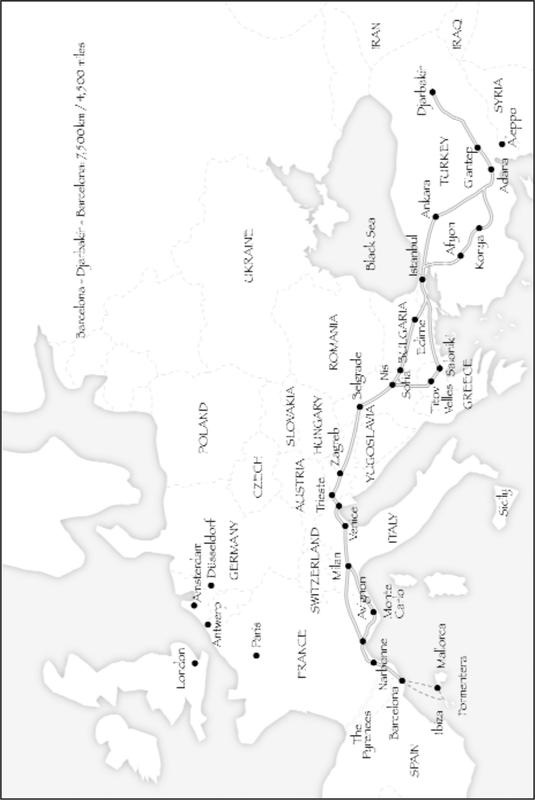

T HAT MORNING, WHEN WE LEFT for London, I rose in the dark and went into the big kitchen where the double doors were open to let in the pre-dawn light. I found Hanna squatting by the embers of last nights fire in the big hearth set into the gable wall. A lighted candle stood on a stone beside her, and she was pouring boiling water from a blackened saucepan into a jug, making me coffee. I pulled on my old Cuban-heeled boots and stood in the doorway for a minute, looking out at the sky still filled with stars, and the dark line of the sea below them. On the camino, by the gate, I saw cigarette tips glowing in the darkness: Rick and Carlo, waiting; maybe theyd been up all night. At the fire, Hanna held out a cup of coffee and a plate with bread and sardines, but I was too excited to eat and, besides, we had a nine- kilometre walk to La Sabina where wed catch the daily boat to Ibiza, the first leg of our journey to the north. It was September 1964.

After I downed the coffee, Hanna took the candle and I followed her into the bedroom where Aoife was sleeping on a mattress, her rag doll on the pillow beside her. I kissed her lightly on the forehead and we looked at her together, our tiny daughter. We smiled at one another for a moment before we returned to the main room. There, I scooped a mug of water from the bucket by the door, picked up my bag and bedroll and turned to Hanna. She came and leant against me, so warm and soft and small within the shift she wore. When I kissed her, my lips were still wet. I said goodbye.

I had made no promises of when Id be back. Much as I would have liked, in that tender moment, to make them, I didnt. I loved her, but what we had together wasnt yet enough. She hoped that, in time, it might be, and I did too. Meanwhile, who knew what this journey held? I had to be free, but I wouldnt deepen the wound with promises, if a wounding, sooner or later, there would have to be.

On the camino, I made out Ricks shape by his hat, and moonlight glinted on Carlos spectacles. The camino was broken, but there was light now from the moon, and off to the east the sky was brightening.

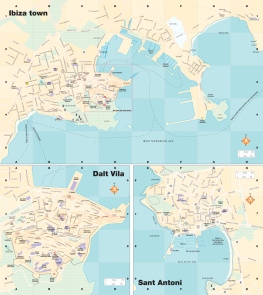

We passed through San Francisco Xavier without talking. It was still and silent, like a border village in a black-and-white cowboy film, the big, white church throwing a shadow over the main square of pitted bedrock, and the few squat houses that comprised the village cut out in moonlight and shadow. Then, onward, on a better camino leading to the road which ran the length of Formentera, twenty kilometres from Salinas in the north, past San Fernando which had electricity, a pensin and a bar to the Mola, a big table-land at the south-eastern end.

The road was wider but not much better surfaced than the cart tracks and caminos. The only traffic that used it was the old island bus, which went to the boat mornings and evenings, and Longinis battered jeep. Longini had been the only foreigner on Formentera for years. A one-time Louisiana lawyer, he lived with his wife, reputed to be an heiress, smoking dope and spending his time reading and killing flies on his veranda, which was screened with mosquito netting: he had a strange fixation about flying insects of any kind. The only other long-term foreigner was Briefcase Hans, a German who had a steel plate in his head which caught the sun, and who could be seen occasionally in a suit boarding the Ibiza boat, a briefcase in hand. He lived on a finca surrounded by trees and thorn bushes with Eingang Verboten and Entrada Prohibida signs on stakes to keep out intruders.

As for the rest of us, we were the newcomers, coming and going, staying as long as we could, sincere seekers after knowledge or simply a kind of freedom, attracted by the remoteness of the island and the cheap farmhouses to rent. None of us were more than thirty years old and there were rarely more than a dozen of us, a band of dropouts of various nationalities, united by our use of marijuana and LSD. We were forerunners of a culture soon to sweep the coffee shops and colleges of Europe but it was secretive then; if you smoked grass you didnt talk about it even amongst the expats in Ibiza, the island of hedonism and liberty. Dope-smokers were different, with a language and code of their own.

Hanna was English. I was the only Irish citizen around. Three years before, when I was living on Ibiza with Nancy, my ex-wife, Id sometimes cross to Formentera. Id spend a night or two in San Fernando at the pnsion Fonda Pepe just to get away from Ibiza and the bad trip that was happening with Nancy and to try to write poetry, which was what Id come to those islands to do. I no longer tried; in the light of the new reality, it seemed wrong to arrest life and reflect, to leave the Here-and-Now and get entangled in words which were so unsatisfactory for communication anyway.

LSD had changed my mind about a lot of things, although we had taken it only once, Hanna and I. Afterwards, we had left Ibiza and gone to Formentera to live out the reality we had seen. That first time, we had only twelve pounds cash and hadnt been able to stay long. Forced to go back to London, we had fiercely held on to the vision we had seen, worked hard, saved and returned with enough money to last us for maybe a year. Our hope was that we might habituate ourselves to a new way of thinking, a perception outside the twentieth century values so destructive and dangerous for us and our children. Hanna and I humbly, passionately and naively hoped for redemption from the culture that countenanced war and nuclear showdowns, from all we had ever learned. And we loved Formentera, the peace there, the friends and the simplicity of life.

But the plan had gone wrong. Out of the heat-haze hanging over the island one June day, my old friend Mel, an American Id known in Ibiza and in London, came limping down the