Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Contents

To Elsie Duncan-Jones

Introduction

The artists studio, a spacious octagonal room, has just one source of light, a large window high up in one of the walls, through which Londons cold grey sky casts an even wash over the painter and the sitter. A fire burns in the grate, which is surmounted by an elegant mantelshelf, and the smell of smoke mingles with the more pungent odours of linseed oil and turpentine. There are several easels, supporting various works in progress, and a four-foot-high fire screen whose surface is a looking glass which can either reflect light onto the sitters face, or, if placed at the correct angle to the easel in use, enable the subject to inspect the artists progress. On a low plinth stands an upholstered chair whose feet have been modified by the addition of castors so that its occupant can be swivelled by the portrait painter to the most precise and flattering angle. Background colour and texture, and more light control, are provided by a tall two-leaved screen, over which different fabrics from the painters rich stock can be draped to emulate tapestries or high-hanging curtains.

Joshua Reynolds, the most fashionable portrait-painter of the day, is at work. His sitter appears to be another artist, also at work a woman, who has momentarily lowered the drawing implement in her right hand but holds in her left hand a large portfolio. She presents herself as a serious artist. Dressed simply in a loosely draped gown of some soft material, sash knotted under her breasts in the classical manner, but the sleeve tied up in workmanlike style, she turns away from her drawing pad to contemplate the studio. Her expression is grave, belying a reputation for wit and gaiety, and her features composed lustrous dark eyes, firm brows, a determined chin. She looks like someone who is in control of her life.

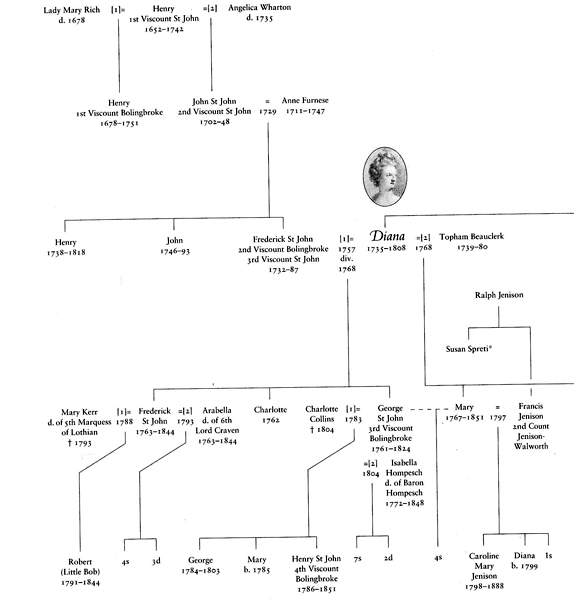

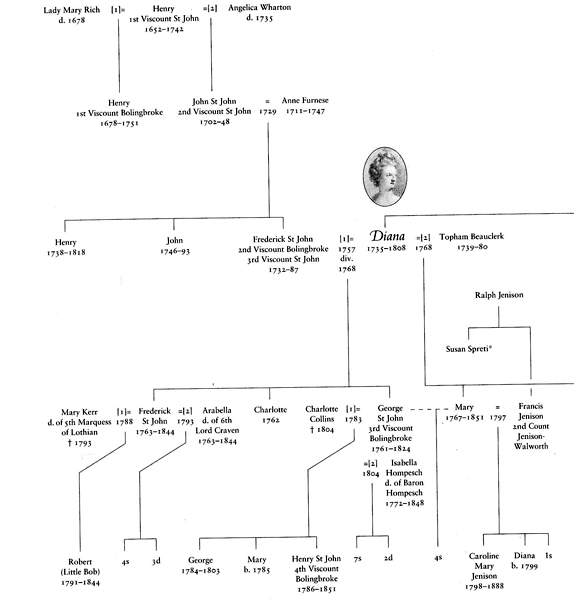

But the artists work is the creation of images. Self-presentation can be as deceptive as the most flattering of portraits. As the young Viscountess Bolingbroke posed as a maker of art, it was her performance that imperceptibly moderated Reynolds oil and canvas interpretation of her. To be depicted as an artist meant that her commitment to a noble activity which concerned eternal values and ideals, and which enabled the practitioner to soar above the petty and mundane, was recorded both for the contemporary spectator and for posterity. The practice of art, for this woman, already represented an escape from daily tensions and underlying deeper worries. Her poise masked personal problems of health, of money, of the heart.

Being fitted into Reynolds busy schedule in the spring of 1763 required dukes and duchesses, politicians, actors, respectable and disreputable women alike to attend his recently extended premises in Leicester Fields, with its impressive purpose-built studio and adjoining gallery. Recently completed portraits were exhibited for the admiration of friends and family, who were welcome to visit the sitter (Reynolds booked in several subjects each day); one such work, displayed while the Viscountess was sitting, depicted one of her husbands mistresses, a coincidence which had attracted the attention of the gossips.

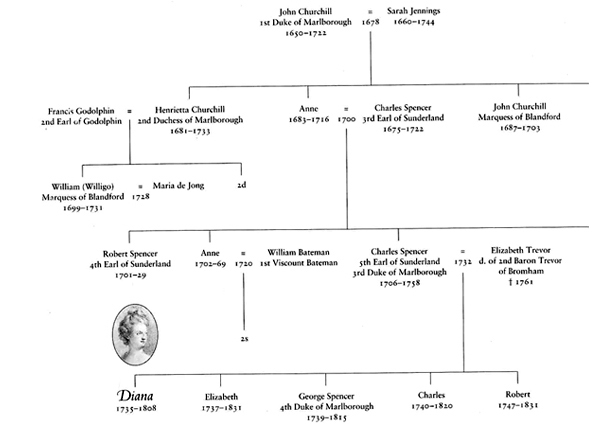

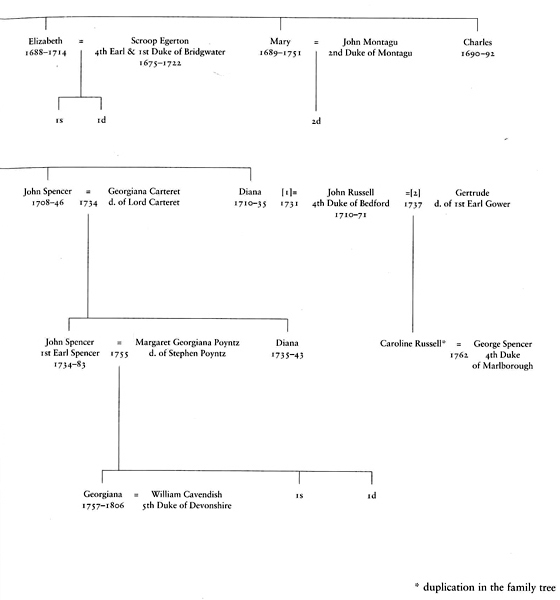

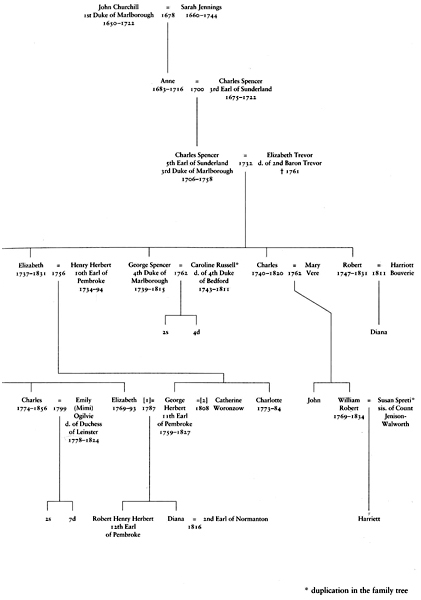

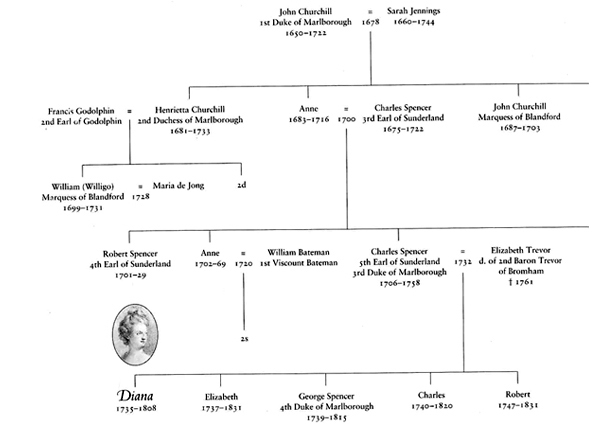

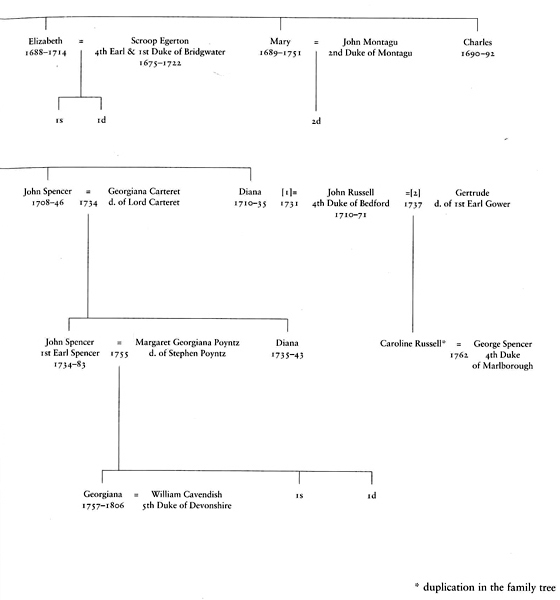

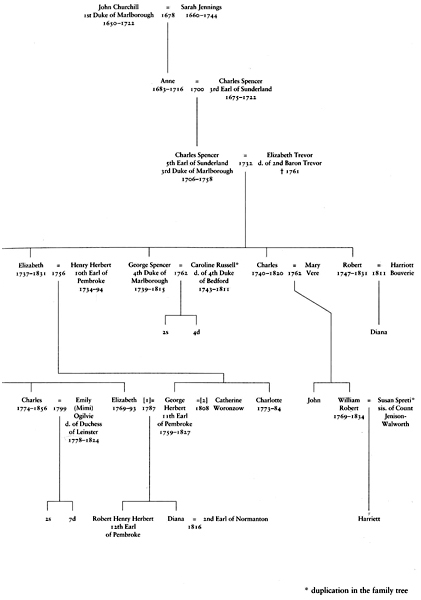

But it was not only her husbands infidelity which was causing concern. There was his uncontrollable extravagance the debts, which had been temporarily alleviated by her own marriage portion (admittedly rather modest considering that she was born Lady Diana Spencer, the eldest daughter of the Duke of Marlborough), had again piled up, and the hard-earned salary from the mind-numbing service which she endured at the dowdy court might be thrown away by him in one afternoon at the races. He was even now exploring ways of eating into his own inheritance, and therefore that of their two-year-old son, by selling off lands and properties that had belonged to his family for generations. Enshrined in the very background of the portrait being painted was a large and rare French vase, the sort of item whose compulsive purchase had contributed to their financial plight. Bolingbrokes reckless collection of such treasured status symbols undermined her self-projection as industrious, independent artist: a wife, like a vase, is owned by a husband.

A more ominous shadow was being cast by his emotional instability. A wild young man had not been settled by marriage, extremes of mood were further fuelled by drink. She was pregnant again, the third time in three years the sash of her robe is tied discreetly high over a gently swelling belly. Her firstborn, George, was healthy, but the second baby, a girl, had died when just a few months old, less than a year before. There was obviously fear for the future, further aggravated by the sickening awareness that her husband was sporadically infecting her with a sexually transmitted disease. The projected image of a serene, noble artist veiled a restless, anxious woman.

Although this was the role she had managed to create for Reynolds, posterity knows her better from a later part, in which she has been irrevocably cast by Reynolds friend Dr Samuel Johnson. As recorded by his devoted biographer James Boswell, Johnson said of Lady Di: My dear Sir, never accustom your mind to mingle virtue and vice. The womans a whore and theres an end ont. We do not know his tone of voice, whether he was smiling, or speaking with tongue in cheek. But he was talking about someone who had now become the wife of one of his dearest friends, in whose house he was welcomed and at whose table he regularly dined. Her crime, in Johnsons eyes, was to have broken the sacred bonds of matrimony through her well-publicized adultery with Topham Beauclerk, which had resulted in a notorious divorce from Bolingbroke, followed by marriage to her lover. Johnsons view was an extreme one, at the end of a whole spectrum of disapproving responses which served to give her name an aura of glamour and sin.

And it was the resulting ambiguity of Lady Dis personal reputation that she managed to turn to advantage in the pursuit of her career as an artist, so that she was able eventually to earn money from her skills, a factor that singles her out from so many other women practising art at the time. The term amateur was barely formulated in the second half of the eighteenth century, and it did not have the derogatory meaning it has today. People of rank were well trained to practise art, as well as to collect and to appreciate it, all morally improving activities whose status had to be defended at a time when patronage was extending from the aristocracy to the professional and merchant classes. There was almost a fear that the encouragement and acquisition of art was being seen as a form of financial investment rather than as the reinforcement of social standards; there were debates about the influence and role of the fine arts, in an attempt to offset the undeniably commercial function of art in an age of leisure. It was certainly a time of widening access, through the first public exhibitions, the vigorous print market, and the new genre of art criticism in the expanding popular press. Polite society decreed that it was necessary to develop genuine taste in order to promote morality through art. So the study of painting and the liberal arts remained an important element of education and of daily life. Art was respectable, and women participated fully as patrons, viewers and practitioners.