Table of Contents

Straightforward and

Brilliant Thinking

Now that shed measured the amount of radiation given off by uranium, the next question was: Did other elements besides uranium emit these strange rays? The only way to find out was to examine all the known elements.

Very persuasive when she needed something for her work, Marie begged and borrowed samples of elements from other scientists, including some of her old professors. She now went through Mendeleyevs periodic table of elements, testing them one by one. The mystery rays werent just peculiar to uraniumshe discovered that they came in a weaker form from thorium (a mineral element discovered in 1828) as well. Her findings were that only the elements uranium and thorium gave off this radiation.

In April of 1898, Marie made a report to the all-important French Academy of Sciences. The eminent men at the meeting listened to a report on frog larvae. Then Maries report, called Rays Emitted by Uranium and Thorium Compounds, was read aloud by one of her professors. She couldnt read it herself because she wasnt a memberno women were allowed.

To Caitlin Krull, future neurosurgeon

K.K.

Acknowledgments

For help with research,

the author thanks Dr. Lawrence M. Principe

Special thanks to Janet Pascal, Patricia Daniels,

Robert Burnham and Patricia Laughlin,

Frdrique Moursi, Paul Brewer, Cindy Clevenger

and the Rabbits, and most of all,

Jane OConnor.

INTRODUCTION

If I have seen further [than other people] it is by standing upon the shoulders of giants.

Isaac Newton, 1675

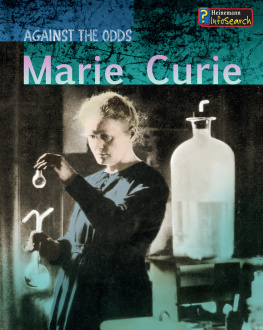

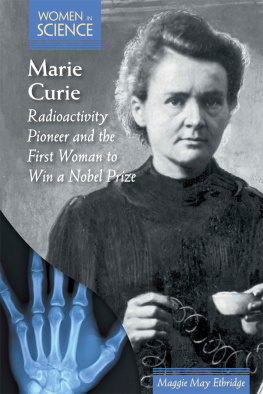

SHE RISKED HER LIFE for science. That much is undeniable. Yet the myth of the selfless Marie Curiealways with a saintly halo over her headis far less fascinating than the complex life she did live.

True enough, she was a genius, winning the prestigious Nobel Prize not once but twice, for Physics and then for Chemistry. She married a gifted scientist who dropped his own research to help with hers because it was more groundbreaking work. And she passed on her genius genes to her daughter, who went on to win a Nobel as well.

Marie Curies permanent claim to fame? She discovered radium and poloniumtwo new elements, or substances that cannot be broken down any further by chemical means. Lots of elements exist in naturetoday we recognize more than one hundred, with new ones still being discovered. But as the Nobel Committee of 1911 pointed out, the discovery of radium in particular was much greater than the discovery of other elements. The radioactive rays it emits can be deadly, as Maries own family was to learn, but radium heralded exciting developments for treating cancer and opened a whole new world of atomic physics.

With radium, Marie didnt just make a stunning contribution to medicine. In experimenting with elements that are radioactivea word she coined herselfshe fostered a greater understanding of the very nature of matter. With amazing foresight, in only her second paper on radioactivity, she called it an atomic phenomenon.

The atom: that building block of all matter. Since ancient times, the atom was believed to be unchangeable, indivisible, the absolute smallest thing that exists. But Curies work paved the way for other scientists to investigate what went on inside it. She spurred the discovery of subatomic particles that make up atoms. Ultimately, her work made possible the development of the deadliest weapon in historythe atomic bomb. How she would have hated knowing that! Nevertheless, Marie Curie helped provide the foundation for the atomic age in which all of us live today.

Marie had a tight-lipped, tough sidestubborn, consumed by work, a bit of a martyr. But she wasnt a robot or a goody-goody. Indeed, she said, I feel everything very violently, with a physical violence.

This was a woman men threatened to fight duels over, someone so passionate about science that she used nine exclamation points to indicate an experiment going well, a person who dreaded publicity and yet was chased by paparazzi. By her mid-thirties, Marie Curie was a celebrity, one of the first people to be the subject of tabloid headlines. Her life story involved broken love affairs, death threats, sances, nail-biting competition, juicy scandal, great losses, and especially a fierce struggle against the strictures of nineteenth-century society. All her life she dealt with No Girls Allowed signsthey were everywhere.

Luckily, she had almost limitless reserves of patience. She spent eight years working in unsatisfying jobs before she could get to college. Later, she took almost four years to isolate her new element, radium. What stands out in her story is the amount of persistent hard work that science can entail.

As Marie herself put it: A great discovery does not issue from a scientists brain ready-made... it is the fruit of an accumulation of preliminary work. Or, in other words, a great scientist is never an overnight success. It takes years of hard work as well as taking advantage of the hard work of other great scientists who came before. As Isaac Newton said in his famous quote, he was able to see further thanks to his debts to others. So who helped Marie to see further?

Robert Boyle, for one, who was an English natural philosopher working at the same time as Newton. (The word scientist wasnt coined until 1834.) Although he worked as an alchemist, searching for a way to change worthless metals into gold, Boyle also compiled an important book on chemistry. In 1661, in The Skeptical Chymist, he laid down some of the preliminaries of this new field, including the definition of an elementany substance that cant be broken down into a simpler substance.

Chemistry took a giant leap forward in the next centurywith Frenchman Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier. In command of the best private laboratory in the world, Lavoisier wrote Elementary Treatise of Chemistry in 1789, providing a much more detailed definition of what constitutes an element, and proposing the first table of known elements. Five years later, after the French Revolution, the unfortunate Lavoisier, a well-off tax collector, was sent to the guillotine.

dmitri Mendeleyev was able to stand on Lavoisiers shoulders even though the Frenchmans head was no longer attached to them. In 1869, this Russian chemist wrote The Principles of Chemistry. Inspired by his favorite gamesolitaireMendeleyev set up a table, or grid, to organize the elements. He used a method similar to the way a solitaire player lays out cards, by suit in horizontal rows, by number in vertical columns. Each row of his table he called a period. Establishing a pattern, he devised what we call the periodic table of all the known elements. In Mendeleyevs time, some sixty elements were officially recognizedlike oxygen, hydrogen, nitrogen, and uranium, discovered in 1798. The table we use today comes from his table.

By Maries day, the climate for scientists in France had vastly improved since the time of the Revolution. In part, this was due to the great Louis Pasteur, who in 1868 revolutionized medicine by discovering that bacteria could cause disease. A French national hero, Pasteur inspired Marie by calling labs sacred places where humanity grows, fortifies itself, and becomes better.

In much of her early work, Marie was encouraged and assisted by her husband, Pierre Curie. Work was such a driving force of her life that its impossible to imagine her marrying anyone other than Pierre, an important scientist in his own right. In 1895, the couple became intrigued with the German Wilhelm Rntgen, who discovered X-rays, and the French scientist Henri Becquerel, who was studying the fascinating rays that were emitted from uranium. Building upon the work of these two physicists, Marie found her lifes obsession: adding two new elements to Mendeleyevs tablepolonium and radiumand researching them further.