Published by Melbourne Books

Level 9, 100 Collins Street,

Melbourne, VIC 3000

Australia

www.melbournebooks.com.au

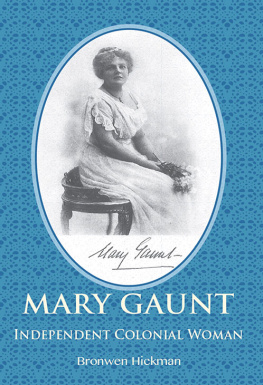

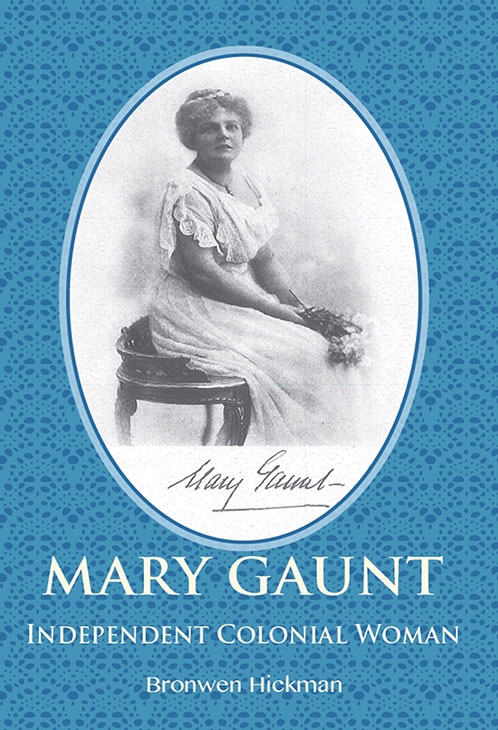

Copyright Bronwen Hickman 2014

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publishers.

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication entry

Author: Hickman, Bronwen

Title: Mary Gaunt : independent colonial woman

ISBN: 9781922129840 (eBook)

Notes: Includes bibliographical references and index.

Subjects: Gaunt, Mary, 1861-1942.

Women--Australia--Biography--20th century.

Women novelists, Australian--20th century--Biography.

Women travelers--Australia--Biography.

Dewey Number: A823.2

Digital edition distributed by

Port Campbell Press

www.portcampbellpress.com.au

eBook Conversion by

Contents

r

Introduction

I have relied on evidence from a most unreliable source Mary herself. No diaries or journals of hers have survived (or have been found), and she did not keep letters. The few people still alive who knew her have only limited recollections, so I have had very few witness statements. It was fortunate that I found her unpublished autobiography when I had almost finished the book, and was therefore better able to evaluate what she had to say.

Long before her autobiography appeared, I plundered her fiction for biographical evidence. This is a dangerous practice. Apart from the obvious she might be making it up, as fiction writers tend to do it does not allow for shifts and changes in cultural context, for the inevitable shaping of life to fit the text, for poor memory, or for glamorising of the less attractive aspects of life. While we might be scrupulously honest in what we tell our family and friends, we can lie to readers with impunity.

Mary Gaunt, by modern standards, was racist; she genuinely believed in the superiority of the British over the coloured people she met in Africa, China and Jamaica. It seems pointless to judge and condemn her because of it, but more useful to evaluate how well or badly she behaved towards Africans, Jamaicans and Chinese. She was a writer; she was interested in everyone and everything. She looked at people all over the world with curiosity, occasionally exasperation, but almost always with tolerance and acceptance. (It has to be said, though, that she was less accepting and tolerant when she felt that the subjects of her interest did not treat her with the respect that was due her as British!)

I have not been concerned with Marys literary achievements, nor made comparisons with other writers of the time; rather I wanted to write about a person of remarkable ability and determination who was also a successful writer. She lived at a time when neither ability nor determination was considered desirable or nice for a young lady. She broke down barriers and championed the right the desirability of women to earn their own living, and provided great role models by ensuring that many of her heroines did just that.

Quotations of Marys own words come from her unpublished autobiography, Strange Roads , written over several years and revised when she was in her seventies in Bordighera. The manuscript is owned by her family in England; there is a photocopy in the State Library of Victoria.

All Chinese place names are written in the Wade-Giles Romanisation, which Mary used in her books. For example, Peking is used rather than Beijing.

All titles of books with no author name are by Mary Gaunt. There is a list of her novels, articles and short stories at the end of this book.

Bronwen Hickman,

Melbourne, 2014.

Chapter

The Letter

My daughter Miss M. E. B. Gaunt, having some time since passed the Matriculation and Civil Service Exams, is desirous of attending the Arts Course at the Melbourne University. Will you be kind enough to let me know what steps it will be necessary for her to take, the fees payable and the date it will be necessary for her to take up residence in Melbourne. Would you also be pleased to say if any other ladies are attending the University. Yours obediently, William Gaunt.

It is the letter that brings Mary Gaunt to life a fleeting glimpse of her in historical records as a flesh-and-blood person. The letter, dated 5 February 1881, is to ABeckett, the registrar of The University of Melbourne. It is written by Marys father. My daughter is desirous of attending the Arts Course at the Melbourne University. So simple a statement, so much weight to it then.

It was a raw, young university, set up in the muddle and bustle of goldrush Melbourne less than thirty years before, and still only a quadrangle in a park. There were less than four hundred students when William Gaunt wrote his letter all male, of course. Nowhere in any of the Australian colonies had a young woman attended a university before.

The letter from Marys father was not the first document in the University Archives about Mary. There was another one her application, five years before, to sit the Matriculation Exam. She applied to do nine subjects: Greek, Latin, English, French, arithmetic, algebra, Euclid, history and geography. These were all of the subjects on offer, except that a candidate could take German instead of French. The application form was filled in by her father, who gave his profession as Barrister at Law and his address as 20 Camp Street, Ballarat, his business address. Beside religion he wrote Church of England, and filled in Grenville College, Ballarat as Marys last place of education. Whatever the status of the finishing school her mother chose for her after Grenville College, William clearly did not consider it a place of education.

At the bottom of the application form Mary added her signature: Mary E. B. Gaunt. Mary for her fathers sister and her mothers mother, Eliza for her mothers mother, Bakewell for her fathers mother. The signature neat, well-formed letters, no-nonsense squarish shapes, shockingly strong-minded her mother called it spoke of education and discipline. It looked very like her fathers.

The application was dated 25 October 1876; the fee of two pounds fifteen shillings was paid, and Mary was assigned the examination number 569. She was fifteen years old and had stepped out of the shadows. After the registering of her birth as required by law, her matriculation record was her second appearance in the historical records of the colony.

Now, having waited five years for the rules to change, she was twenty, a young woman confident of her place in the world. She had fine, light curly hair and regular, even features; not a beauty, perhaps, because of a certain firmness about her mouth and that square, determined chin, and at that time feminine beauty was bound up with the idea of fragility. The eyes that gazed steadily and seriously at her new surroundings sparkled easily into laughter. On the surface were the polite diffidence and restrained manners instilled by her mother and by governesses and private academies; underneath was the exuberance and tomboyish freedom of a goldfields childhood.

She had fought battles to get to this point, overcoming her mothers misgivings, the sarcasm of her younger brothers, and the social and financial hurdle of leaving home to study in Melbourne. And the battles were not only at home. While the university had officially, if somewhat grudgingly, made ready to receive them, much of Melbourne was not yet ready for the idea of ladies at the university.

Next page