You have made the most important decision of your life and the greatest sacrifice a human being can make. Well done Judith.

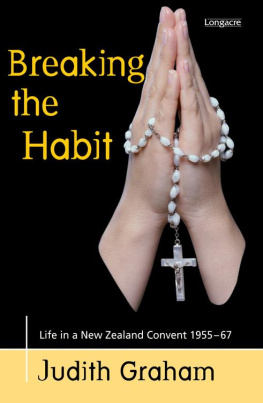

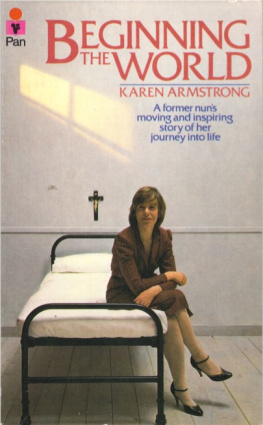

In 1955, at seventeen years of age, Judith Graham entered the Dominican Order and began her life as Sister Stephen. In this compassionate yet frank account she recalls her years as a Dominican nun during the repressive pre-Vatican II era.

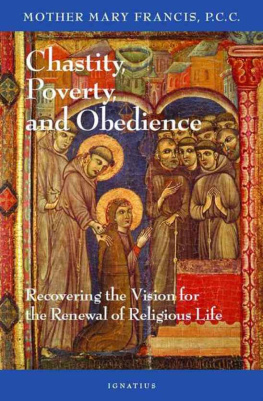

The vows of a nun those of poverty, chastity and obedience encapsulated in the commitment of death to self proved too much for Sister Stephen. Her battle for acceptance and spiritual fulfilment was stifled by the rules and regulations of the Church. Yet leaving the Order was even more difficult. After a twelve-year struggle she escaped from the convent feeling like a battered wife.

BreakingtheHabit, first published in 1992, is a warm, personal story of increasing doubt and subsequent growth, and of freedom of spirit a freedom I will never take for granted. It also captures a way of life that no longer exists, and one womans struggle to regain her sense of self.

The storyisriveting.Butitisthewritingthatdeliversthestory,afterall. Jane Tolerton, TheWaikatoTimes

Quotes from reviews:

before the changes of Vatican II. A world that is achingly familiar to all of us who lived it, but must seem as alien as Mars to the uninitiated. Sister Pauline Engel, NZ Books

though she writes with a humorous acceptance and surprising gratitude for the experience within the priory, she is quite clear about the horror of a system that, for her, denied individuality and stifled creativity. Marion McLeod, The New Zealand Listener

It so touched peoples hearts the mail hasnt stopped coming in. Leigh Bramwell, Next

a special insight into a rare sort of person. Her story demanded that I read it in one sitting. I am not surprised the book sold out within 10 days of publication. Kay Williams, Evening Standard

The story is riveting. But it is the writing that delivers the story, after all. Jane Tolerton, The Waikato Times

A very warm and human tale, telling how a free spirit overcame a system designed to supress individualism. Ashburton Guardian

This could almost be one of those all you ever wanted to know about but could not find out no matter how hard you tried books. Chris James, OtagoDaily Times

This is an uplifting book. Christchurch Star

C ONTENTS

ONE afternoon, visiting my eighty-six year old mother, I found a photograph of me as a nun. Whos this? I asked. A girl I once knew, she replied. I flinched, but remembering the remark years later, I thought it could have been a great title for this book. When the book was first published in 1992, I was surprised at how well it was received because I had intended it to be an historical account for my children and for theirs of my early life. I knew then that that way of life was disappearing fast in a changing world, but it appealed to a much wider audience. Was that because it satisfied a curiosity about nuns? Or was it because it was a personal story about someones journey towards self-knowledge? A journey we all take, though mine was somewhat off the main route. Whatever the reason, here again is the story of a girl I once knew and with whom I can still live.

Judith Graham, 2006

When I was small, which is many years and kilograms ago, my father promised me half a crown if I could keep a diary faithfully for a year. He thought it would encourage me in the discipline of writing. Twenty years later he told me to write this book. And now, another twenty-five years on, facing retirement and a memory that is quickly fading, I recall my life as I see it.

For him and for my mother in gratitude.

And for Reg, Kirsty and Piers, by way of explanation

Judith Graham, 1992

WHEN I was seven years old my mother, like all other Catholic mothers, dressed me as a miniature bride. This was for the most important event of my Catholic childhood. I was to make my first Holy Communion with all the others in standard one at St Josephs School, Papanui. We were to receive the Body of Christ in the form of an altar bread for the first time. Even my sandals and socks were white and on either side of the veil I wore on my head were two bunches of lily of the valley. Their smell, and the music of the First Communion hymn, O Mary Mother, sweetest, best, are my strongest sensual memories of childhood.

The day before Holy Communion we all made our first confessions. Father Timoney was our parish priest, a kindly Irishman who was to hear our confessions after Sister had trained us in the various kinds of sin we could have committed disobedience, lying, unkindness. We learnt about mortal and venial sins: mortal sins meant hell if we died before we had confessed them. To commit a mortal sin required three things: full knowledge, serious matter, and full consent to the evil. If one of these conditions was missing, the sin was venial. All this was laid out in the catechism which we learnt by heart every day. Life was full of terrifying certainties and the most certain of all was death.

If we died not in the state of grace we would go to hell for ever and ever. At the age of seven I found the whole idea of eternity terrifying. And an eternity of hell was unthinkable. Most of the fairy stories I heard ended with the words and they lived happily ever after, but there wasnt much about happiness in the catechism. If you made it to Heaven you were a dead cert for happiness but God made me to know Him, love Him and serve Him in this world and to be happy for ever with Him in the next. It seemed a long wait for happiness.

At St Josephs we were taught in the old chapel school and we were seated in twos at cramped desks on the uneven, rutted floor. The blackboard in front of us had a beautiful border of flowers and grapes wrought in coloured chalks. At the top under the crucifix were the initials AMDG ad maiorem gloriam Dei. We had no idea in standard four what that meant but it was something to do with getting our tables right. We stood in line in front of the board where Sister Aloysius had drawn a clock without hands. When she pointed to two figures we had to add or subtract immediately or move to the bottom of the line, getting a whack over the palm of our hands for not knowing our mental. The sevens table was my frequent undoing.

I was beginning to become a hated goody-goody by about standard four. To be a saint like the popular St Therese of Lisieux, or Little Flower as she was called, was something we were all taught to aspire to I took it very seriously. Being a saint meant praying a lot, making Acts eating what we hated, smiling at people who laughed at us or said things like Youre a fatty. It especially meant we had to be different from those around us. My mother told me to look at the fir tree The nearer you are to God, the lonelier you are. There arent many branches at the top.

Being a saint also meant I had to please God in all I did.

I decided the best way to begin any day was to get up at 6.30am and bike to mass at St Josephs, our parish church, about fifteen minutes away. There werent many people there and I felt special going into the semi-lit church, smelling the candles and kneeling in the shadows with the seven or eight adults.

One morning Father Timoney said before he started mass, Ive no altar server. Would you act as altar boy, please Judith? I was terrified. Girls were not allowed in the sanctuary unless they were cleaning it or setting the altar or arranging the flowers. I hadnt ever read the Latin aloud but I couldnt refuse either. I went up to the altar rails and knelt down with my missal open.