Table of Contents

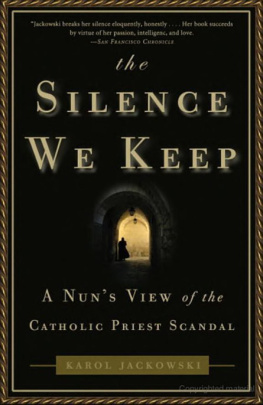

Also by Karol Jackowski

Ten Fun Things to Do Before You Die

Sister Karols Book of Spells and Blessings

The Silence We Keep: A Nuns View

of the Catholic Priest Scandal

Good Cooking Habits: Food for Your Body,

Your Soul, and Your Funnybone

RIVERHEAD BOOKS

a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

New York

2007

This book is dedicated to

my mother superior,

Shirley Jackowski.

introduction

There is nothing more interesting to me than what we decide to do with the life weve been given. The choices we make, the paths we take, whom we choose to love, the work we do, how we play, the beliefs we hold to be truethose are the ingredients that make up the mystery of our lives. This isnt a book about nuns as much as it is the story of what I chose to do with my life and the magic that makes up its mystery. This is my story of the first seven years on the least traveled road of becoming a nun; the first steps I took on the spiritual path that led to the fullness of life I know now.

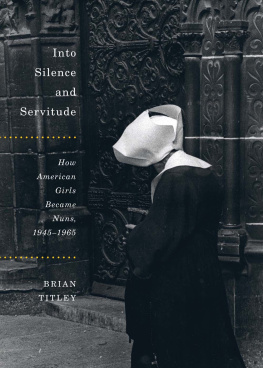

While any one of us will tell you that it takes a lifetime to become a nun, the first seven years are the most dramatic, the most traumatic, and the most formative in a nuns life. Those years transformed us from eighteen-year-old college students into Sisters of the Holy Cross at Saint Marys in South Bend, Indiana. While college years naturally provide times for ones individuality and personality to be explored and transformed, for the women who became nuns with me they were years of total self-denial: nun of this and nun of that. During these seven years we were melted down and molded into the image and likeness of a nun. Catholic religious communities even referred to those years as a time of formation, which began the day you entered the convent as a postulant and ended formally on the day of final profession; the day of forever and ever, amen.

This is the story of those years and my struggle to become a nun without losing my fun-loving soul. What made these years uniquely dramatic, and for many sisters uniquely traumatic, is that we entered them in the 1960s, at a time of profound cultural and societal change. We were the baby boomers of 1946. President John Kennedy was shot while I was taking a test in religion class. The Peace Corps had begun a few years before, and the Vietnam War was growing more serious. Protest movements for civil rights, feminism, nonviolence, and equality erupted all over the country. Unrest became so palpable in those days that it gave birth to a kind of music never heard before and a way of life we never experienced. The call to hammer out justice, freedom, and love all over the land is the call I heard in wanting to be a nun; and on that tidal wave of protest I entered the convent. The times were a-changin, to quote Bob Dylan, and so was I.

Nuns too stood on the verge of revolutionary changes then, though I didnt know it when I joined. Even the Catholic Church and the cloistered lives of nuns couldnt keep out the kind of liberating spirit that charged the country. In 1964 I wore the full postulant habit of the Sisters of the Holy Crossa floor-length black dress, with black cape and white collar, and a black veil with a narrow white headbandand professed final vows seven years later, unveiled and in a relatively stylish navy blue suit. (Regardless of what we wear, its still not hard to spot a nun in a crowd.) The traditional habit worn for centuries was replaced by street clothes. No longer only face and hands, nuns all of a sudden appeared unveiled; with the change of habit, individuality was born in the sisterhood.

The lifestyle of sisters changed dramatically in those seven years. Like butterflies coming out of cocoons, we no longer lived cloistered or secluded. Groups of sisters moved from castlelike convents in remote privileged areas into low-income neighborhoods and small apartments. As we became part of peoples lives in ways that were once forbidden, our homes became social centers, soup kitchens, and shelters. A life once so extraordinary in its secrecy and exclusiveness opened its doors to welcome all. The lives of nuns turned inside out and upside down in those years, causing an unprecedented revolution within the sisterhood, the long-term effects of which continue to unfold.

The changes that took place in womens religious communities between 1964 and 1972 as a result of the Second Vatican Council were unprecedented. Some historians refer to those years as the bleeding of the sisterhood. Once a powerful workforce in the Catholic Church, nuns began disappearing from all the old familiar places like schools, parishes, and hospitals. More than two hundred thousand women left the convent in the years following Vatican II, accompanied by a drastic decline in new applicants.

My own experience bore out the trend. In 1964 fifty of us joined the Sisters of the Holy Cross. In 1972 seven professed final vows. Of that seven, three of us remain in the sisterhood. We were the last real bumper crop of postulants. In the years to follow, the number of new sisters dropped drastically from something like fifty to forty, then to twenty, then thirteen, then seven, then years of no new applicants at all. For American religious communities today, a handful of applicants may apply every year or two, at most, but the golden days of fifty to seventy-five new sisters every year is now ancient history.

Why did so many sisters leave the convent during those years? Prior to 1972 it would have been common for a few sisters to depart: some were miserable and chose to leave; others were deemed a poor fit by superiors and dismissed. But in the late 1960s sisters began to leave for reasons unheard of before. Our lifestyle as nuns changed so dramatically and so quickly that many sisters faced choices and experiences that challenged their identity as nuns and the reasons they chose religious life. The more ordinary our lives became with the change of habit and lifestyle, the harder it became to define what it meant to be a nun.

As we began living and working with much greater freedom, our lives were no longer controlled by the structure of convent life or suppressed by the will of rigid superiors. Sisters living in oppressive convents (and there were thousands) often sought comfort and community with colleagues in the workplace. As a result, some fell in love with coworkers (often priests) and left the sisterhood to marry. Others accepted their homosexuality and left to pursue relationships. And many became fully committed to social activism, much to the dismay of superiors, bishops, pastors, and even some of the nuns with whom they lived. In 1966, for example, for the first time ever, sisters marched for civil rights in Selma, Alabama. Some did so in defiance of superiors, who forbade their participation in public protest and dismissed them.

These were revolutionary times in the sisterhood. Voices wrapped for years in silence suddenly began to speak. Sisters wanted freedom to make personal choices and decisions about where to live, who to live with, and what work to do. Given the climate of social unrest and conscientious objection, many sought a sisterhood of equals, not one of superiors and subjects.

While I was entering the sisterhood, thousands of the best and brightest sisters were beginning to leave. Many left traditional convents to pursue independent lifestyles, not wanting to abandon religious life but envisioning a more self-governing, self-supporting sisterhood not controlled by superiors, bishops, priests, or the Vatican (all of whom, to this day, legally and effectively govern the lives of nuns). New independent religious communities formed as a result, such as the Sisters for Christian Community founded in 1972, of which I am now a member. Inside and out, the sisterhood became transformed not only by the mandates of Vatican II to modernize but also by the social movements in this country for equality, opportunity, and independence. The way nuns were in 1964 is a way we as American Catholic sisters will never be again.