Miriam Frank

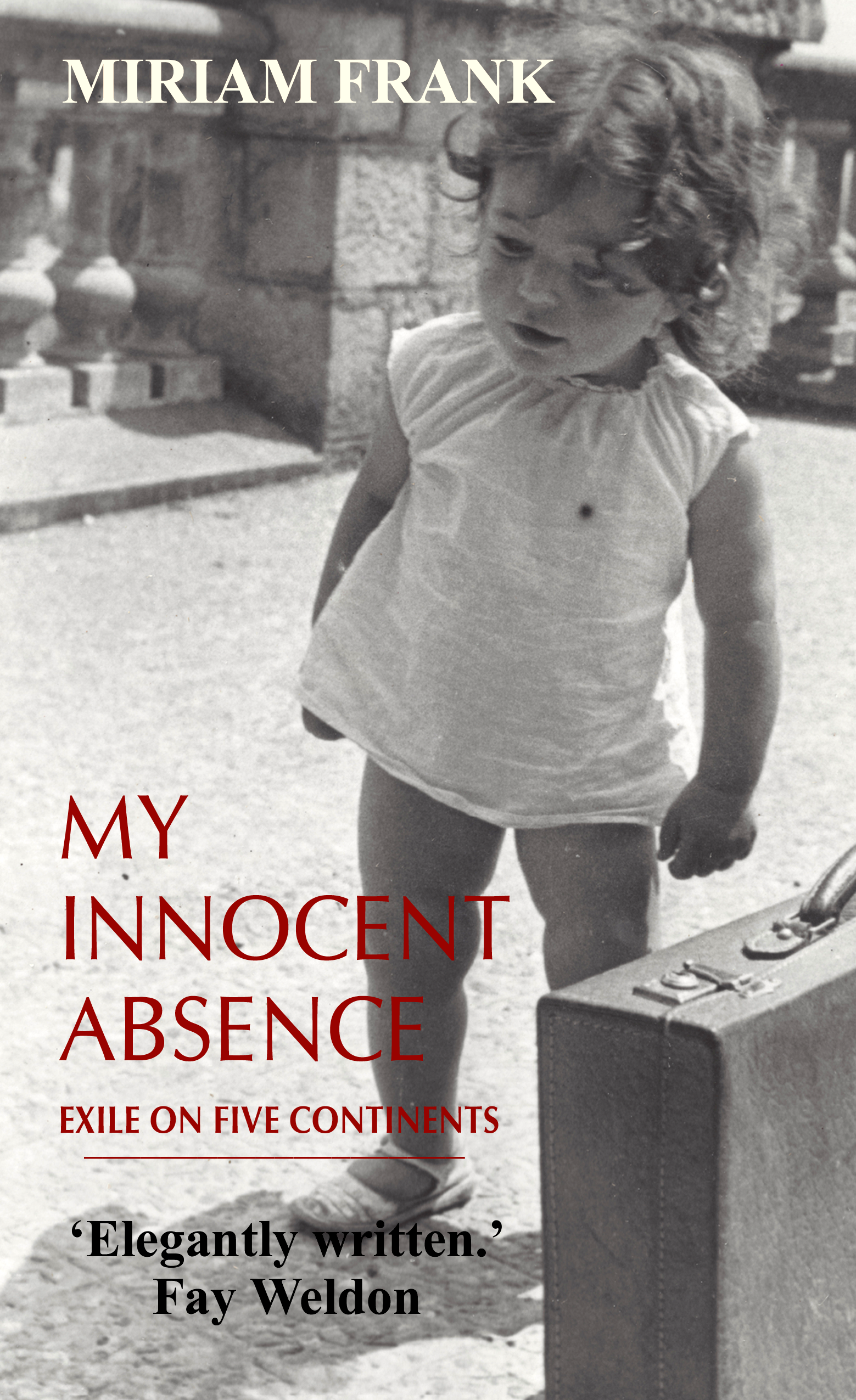

My Innocent Absence

http://www.gibsonsquare.com

Printed ISBN: 9781783341283

Ebook ISBN: 9781783341337

E-book production made by Booqla

Published by Gibson Square

Copyright by Gibson Square

Praise

I found it both atmospheric and, most important, I wanted to read more Carmen Callil

Elegantly written and fascinating Fay Weldon

A poignant and beautifully written saga of migrations, which punctuates the history of our times Moris Farhi

Absolutely riveting Amanda Hopkinson

Frank reviews the period with a fresh eye. This is truly a new story Independent

My Innocent Absence, full of lovely, tactile detail, is the story of a peripatetic life Jewish Quarterly

It isnt surprising that physicians often make excellent writers they are trained to observe. Miriam Frank is one of that great line of physicians turned writers that includes Chekhov, Maugham and Keats. In Miriams case the flawless professionalism of the surgery flows seamlessy into flawless prose that has echoes of Lawrence and Proust. This book thoroughly emerges the reader in the human condition from birth to death and back again Edward Wilson

Her voyages, spelt out in her new memoirs, have nothing to do with the Paul Theroux school of travel writing They became the real life characters at Ricks Caf in Casablanca Camden New Journal

A dramatic and quite gripping autobiography Buenos Aires Herald

Miriam Franks life is the epitome of twentieth-century displacement Esra Magazine

Miriam Frank raconta la sua vita in un libro fantastico, commovente Italia Sera

About Miriam Frank

Miriam Frank is a writer and literary translator, and lives in South-West London. She trained as a doctor and became a consultant and senior lecturer at the Royal London Hospital.

Dedication

For Louis, Max and Serafim, tomorrows people

Inscription

One can no longer say: Im a stranger everywhere, only everywhere I am at home.

D.H. Lawrence

MY INNOCENT ABSENCE

Exile on Five Continents

by Miriam Frank

Prologue

She looks empty.

Kte.

My mother.

Anna, then thirteen, had just entered the room and was looking at her grandmother from the foot of the bed. Her words rang out softly in the silence of the small bedroom.

Kte lay stretched out, serene, in her bed for one. Alone, much as she had lived her life. The timbre of her laughter, warm tones in her voice, her forceful anger, her tender empathy, all stilled. The furrows on her brow deepened by her testing life and urgent impatience smoothed out. Her intense, olive-green eyes, unseeing now, closed for ever.

At peace.

Yes: empty.

On my mothers desk next to Anna, yellow daffodils and Claras photograph were bathed in the soft spring morning sunlight slanting in through the French windows which looked out onto the small, suburban, back garden in this, her latest home in north London. Across the years and in her various homes, she had always kept that photograph of her mother Clara close to her, on her bedside table or her desk: its handsome antique frame dating from her time in Barcelona where the news had reached her of Claras death in Germany.

During her illness my mother had remarked, Ive been lucky. Ive had a long life. And a good one. Think of all the others She was remembering her friends and family in war-torn Spain, France, Germany, in those event-filled days of her youth. Like them, she too could have had her life cut short, shared their grim fates. And I along with her: long before I understood what was going on around me.

In those times we had been inseparable: mother and child, facing together the perils that threatened everywhere to engulf us. Gone now was the tension in that motionless face of her courage and resolve as she faced the Nazi menace sweeping Europe and grappled for our safety. She had been the centre of my world, my everything, then. Till we became estranged I had escaped one of historys most infamous, widespread, methodical slaughters, to find myself cut off from my own source.

I had sat with her through the night and accompanied her in her struggle right to the end. Just the two of us, with the nurse hovering in the background. She had not given up easily. I had tried to be with her, to give her what comfort and warmth I could in those, her last moments, as I felt again our closeness from all the way back to when my life was only just starting; before our conflicts and misunderstandings soured our relationship and threw me into confusion.

And now here she lay. Empty. All she had lived through and experienced, embracing three continents and much of the seismic events of the twentieth century, surrendered. She had arrived at her final destination, while I remained cast adrift, seeking my bearings, looking for answers.

Part 1: DISPERSAL

From a Big House to a Mattress

Casablanca, 1941.

A LARGE PASSAGEWAY Or was it a veranda? Perhaps more like a big empty hall. The floor was stone, or maybe well-worn marble. Tall, sweeping arches across the length of the wall looked over the street or were they windows? opposite our space on the floor against the solid wall. The mattress marked our place. The mattress and the area next to it where all our possessions in my mothers small square trunk and our old suitcase now stood. My mother had dug out my nightdress from among our packed clothes; she was now pulling off my dress as I stood facing her on the mattress ready for bed.

The day had been exhilarating. Never before had I seen such long white flowing robes. They glided along, swathing everyone everywhere. Even those old men sitting about on the ground in the dazzling light, by the side of the dirt road, were wrapped in them. Ce vieux, quest-ce quil fait l-bas, Maman? They also flapped around the lively men rushing and shouting behind their stalls in the open-air bazaar the white canvas overhead curbed the fierce sunlight as I tiptoed round breathlessly examining their unfamiliar wares, resisting my mothers attempts to move me on. Those crossed red and black leather sandals, Maman, please can I have them? That darling little terracotta jug! But oh, the women! Maman, why cant we see their faces? Darting dark almond eyes tantalisingly imprisoned in the narrow gap between the white veils stretched across their cheekbones and the white cloth draped over their heads to slide down into their fluid white robes. And white here was whiter, in this hot bright light. And everywhere the bustle and chatter, the earthy smells, the dusty dirt paths.

But now it was night-time and we were getting ready for bed. Our mattress. One in a long row of straw mattresses, lying side by side, heads against the wall on and on, as far as I could see each lodging a family in transit from Marseilles to Mexico.

You know, Maman first we had a big house, then we had a little house, then we had a room, and now we have a mattress.

The memory of a memory of a memory of a memory like an image caught on facing mirrors that goes on reverberating till it is almost lost

***

Marseilles, earlier in 1941.

OUR LAST NIGHT in Marseilles I had spent with Papa in a small hotel by the port. He had come especially to say goodbye and, my mother explained to me, he had asked to be alone with me for those last hours before our departure the next day. As we came through the door into this new room with its fresh clean smell, Papa put down his leather bag. A large bed in the middle, with its foot nearest the window, took up all the space. Papa sat down on the side of the bed, on its cream bedspread. He was strangely quiet and a little listless, seeming not to know what to do with me now we were here with each other unlike all our past times together when we had never run out of play and chatter.