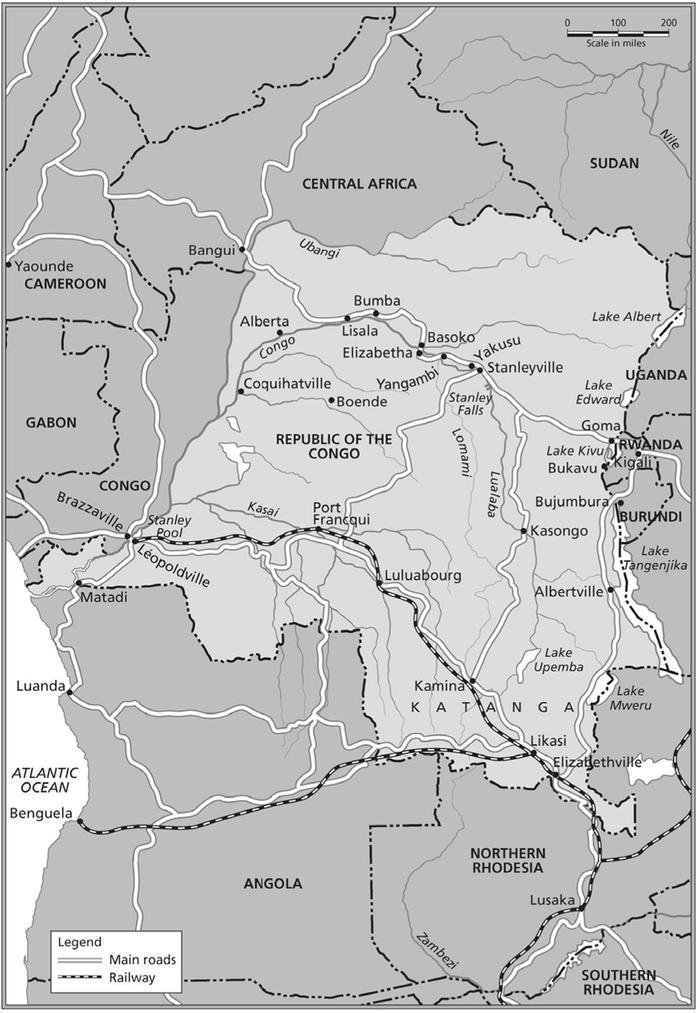

I CAN SEE IT quite clearly. I am outside the store at Elizabetha. It is a dull brick building with a tin roof, one of a rash of European dwellings and offices in a clearing of the plantation above the river. The heat lolls in an air heavy with moisture. In the distance I can hear a patter of drums. Twelve people are being lined up against the wall. Ten whites. Two blacks.

One of the whites is the Portuguese trader. He is a small man with a beer belly and bad teeth, but such spirit. It isnt just his money and his colour that have made him a king; it is his sexual prowess. Even in extremis he carries himself with a certain swagger.

Then there are the nuns. I can hardly bear to think of them. Fluttering, broken birds, this may be their chance to become martyrs, to return in triumph to their maker. But how can they hold up their heads when they have been violated? Wimples awry, they form a confused heap of black and white, like seagulls on an oil-polluted beach.

The old planter and his wife are another thing. Vieux colons, old colonials. Living here so long they have become weather-beaten, intertwined with one another and the jungle. They could face even this catastrophe with equanimity, were it not for the child. That is the part that is unbearable. The child should be at boarding school in Europe, but she is still young too young for parents of their age. She arrived unplanned and has become so precious they cannot bear to part with her. One of the planters arms is crooked round her head, which he clasps to his chest, while the other holds her body. All the captors can see is a neat back-parting and two thick blonde plaits. His wife stands beside him. She has grey hair neatly pulled back into a bun. Straight and still she is, as she has always been, the rock in adversity.

In contrast, the young planter who lived down-river is in hysterics. He is a nouveau colon. He holds up his two-year-old child to the rebels, shaking her and shouting hysterically until he gets knocked in the mouth with a rifle and collapses in a heap. His young wife is already down on the ground. Mute with shock, she is on her knees. She doesnt even hear her child crying any more. She lifts her head and a silent scream rips the air.

It is the black men, however, that I am most troubled about not the rebels, who are drug-crazed, faceless extensions of a gun but the two Ghanaians. They have stirred up something more complex than pure horror. I see them dressed improbably in torn suits and grubby ties. How else would we know that they are ordinary businessmen caught up in a mess that has nothing to do with them? For the past few weeks they have been trying to escape through the jungle, sleeping beside the mosquito-infested river, hacking their way through the mangrove swamps. They speak no Lingala. Their limbs are stippled with sweat, and the blood has drained from their faces like the colour from a badly dyed garment. As far as the Ghanaians are concerned, these rebels who call themselves Simbas, lions are savages. Young men, barely into manhood, they are doped up with dagga and primitive superstitions. As soon as they were captured, the Ghanaians knew they were doomed. Not only are they foreigners in an alien country, they are middle-class businessmen working for a European corporation. This makes them worse than whites.

How could I have imagined that Id leave the Congo unscathed? That I could simply jet in, live a dream, and jet out again? But then, come to think of it, that wasnt how Id imagined it. Id wanted to be involved. Wanted to make a difference. What I hadnt imagined was that it would all turn out the way it did.

IT WAS A DANK February evening when David, in starched collar and tie, arrived home to a flat draped with nappies and felted-up matinee jackets, to announce that the company had suggested sending him to the Congo. I didnt want to go. Instant visions of mangrove swamps and mosquitoes flooded my mind. Followed by images of disease, death and disaster. The Congo was the armpit of Africa. At the same time, I knew that questioning the companys decision would be futile. This was the early 1960s, when employees fell in with their bosses wishes. And wives did as they were told.

Ever since hed joined the company wed known that David would be sent abroad. We were looking forward to it. He had left his safe job as a chartered accountant to join the burgeoning world of big business. We comb the country, the company chairman had boasted in one of the Sunday newspapers, for the cream of Britains young brains and talent. David was known as a management trainee. He was one of the chosen. Wed envisaged a high-status job in New York or Sydney but the Congo? What was there for a future captain of industry to do in the Congo?

They want me to reconstruct their accounting systems, David said rather grandly. Make long-term financial forecasts. Bring the whole thing up to date.

What about Charles? Charles was our small baby.

Oh, hell be fine. The company wouldnt allow children to go out there if it wasnt safe. The company, he assured me, would look after us in every way. Theyd provide us with housing, a car; even a large hamper of food, chosen by us and shipped out every six months. We would live in luxury. David had never travelled beyond Europe, and I was beginning to sense that he viewed the idea of going to Africa as a bit of an adventure.

And, he added, playing his trump card, they pay half my salary in Congolese francs and half in sterling. We should be able to live on the Congolese francs and save the sterling.

That was the clincher. Apart from the fact that I, too, felt seduced by the exotic idea of going abroad, the money was an undeniable lure. There may have been plenty of kudos in being a management trainee, but the pay was low. We couldnt even afford proper heating.

The winter of 19623 has, rightly, gone down in history. It started with the smog. For those who didnt live through those times, its almost impossible to imagine. A large wad of cotton wool descended on London, making it impossible to see more than a few feet in front of our faces. Traffic was brought to a standstill. In the mornings, David struggled off to the Tube station with a gauze nappy tied across his face to protect him from the polluted air. While the cattle that had been brought up to town for the Smithfield Show died in the confinement of their stalls, Id holed myself up in our flat with my baby. There was a red alert at all the hospitals, which were only taking extreme emergencies. These, we were told, were the elderly and the very young. The pollution was so bad that a saucer of ammonia left on a dresser was neutralized within an hour.

The fog was followed by a cold so intense that it, too, has become legendary. A permanent film of ice had formed inside the kitchen window and icicles hung over the sink. The only faint warmth came from a pathetic gas contraption, and an electric heater with one bar. There were no washing machines in those days, or at least I didnt have one, and I had to scrub everything by hand. I am by nature, or upbringing, a Spartan, and I regarded lugging my baby and his pram no handy pushchairs in those days down three flights of stairs as a challenge. Yet my capacity for endurance was being seriously tested. Id forgotten what it felt like not to be cold. Rhodesia, where my parents had decided to settle when I was ten years old, might have been a cultural desert but it was warm. The Congo was becoming more and more alluring.

There was, however, one pretty hefty fly in the ointment, and that was the racial question. No one who had grown up in 1950s southern Africa could have been unaware of this. It was undeniably there, part of the privileged, balmy air we basked in. But history was shifting. India had been granted its independence; South Africa had been made a dominion like Australia and Canada. Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), on the other hand, was what was known as a crown colony. This meant that the country ruled itself, or rather was ruled by the small proportion of white settlers. Opinions, however, had begun to divide, and the status quo had already been shaken when the Nationalist party was voted into power in neighbouring South Africa and introduced the infamous policy of apartheid.