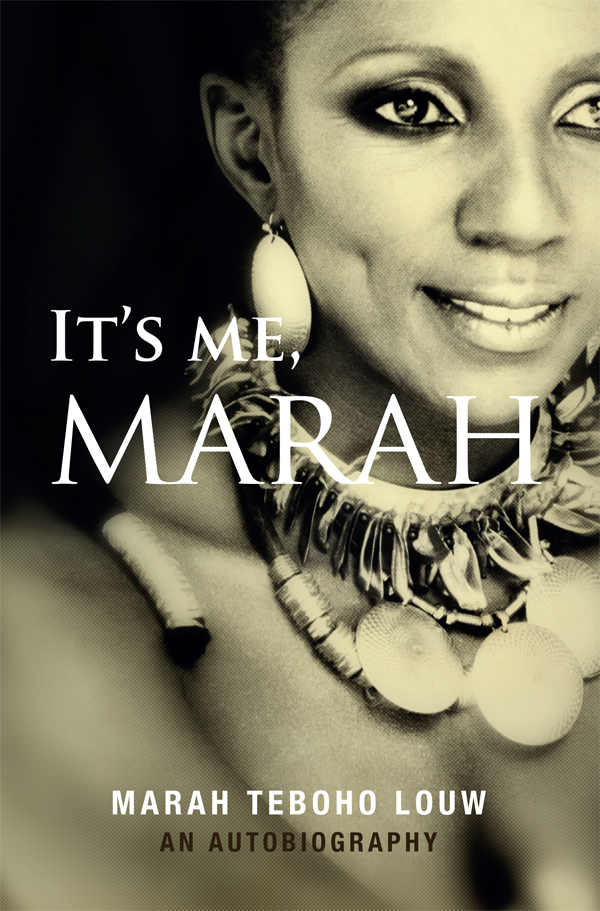

Its me, Marah

An Autobiography

Marah Teboho Louw

First published by BlackBird Books, an imprint of

Jacana Media (Pty) Ltd, in 2017

10 Orange Street

Sunnyside

Auckland Park 2092

South Africa

+2711 628 3200

www.jacana.co.za

Marah Teboho Louw, 2017

Cover photo: Fiona MacPherson

All rights reserved.

Cover design by Palesa Motsomi

d-PDF ISBN 978-1-928337-38-6

ePUB ISBN 978-1-928337-39-3

mobi file ISBN 978-1-928337-40-9

See a complete list of BlackBird Books titles at www.jacana.co.za

I dedicate this book in loving memory of:

My sister and mother, Trueblue Mabasotho Louw,

My parents, Charlotte Macindi Louw and

Reverand Mokgethi Benjamin Louw,

My daughter, Moratuoa Charlotte Ratu Louw,

My paternal grandmother, Mamaikele Amy Louw,

My maternal grandparents Reverand Brigg Nkolongwane and

Ellen Nkolongwane,

And all the children, grandchildren and

great-grandchildren of Bataung and Nkolongwane amaCindi,

The Khoisan people, the original inhabitants of South Africa,

from which we Bataung ba Barwa come from,

Last but not least, my beloved village of Boomplass in Herschel,

Eastern Cape, and my kasi Mzimhlophe, Soweto.

Contents

Prologue

T HERE WAS A DAY IN M AY 1972 which shook my understanding of my family and myself. Looking back now, I can see how the foundations cracked when my sisters boyfriend David hammered on the door of my parents home just before sunrise. He staggered inside, his arms wrapped in bandages, and wept uncontrollably as he tried to tell us something so garbled by his tears that my mother and I struggled to make sense of it.

His words, when they finally became clear enough to understand, were devastating: my sister, Mabasotho Trueblue, was in Baragwanath Hospital after being severely burnt in an accident involving a paraffin stove.

I took a taxi to the hospital. It was too early for visiting hours, but sheer determination got me into the burns unit. A nurse pointed me in the general direction of Trueblues room and I wandered up and down the ward, becoming increasingly panicked as I failed to find her among all the other patients, some of who were so badly injured I could barely stand to look at them. I went back to the nurses, but they were as disinterested as I was desperate. Eventually though, one of them led me right up to my sisters bed.

I would never have found her otherwise. Her entire body, including her face, was covered in bandages. I had walked past her earlier. I leant in as close as I could and whispered my name in her ear.

Ke nna Teboho.

Only her mouth was exposed, her lips swollen. But at least that meant she had the power to tell the truth about what had happened to her.

Many aspects of that day have come to be part of patterns that have recurred throughout my life and even defined the person I have become. It began with an alarming disruption by a deceitful man, and Ive encountered many of those. Later, I wandered, determined but unsure, struggling to get guidance from people who should have shown me the way but didnt care enough to do so. I hadnt known who my sister really was, and finding her was painful. The truth, Ive realised, can be difficult to track down and face. But Trueblue had the strength to tell her story, and now I have done the same.

Chapter 1

I WAS BORN M ARAH Teboho Louw on 17 July 1952 at Nokuphila Clinic, otherwise known as Bridgeman, and now Gardens Clinic. It looks very different to what it was on that cold winters day. I dont know the exact time of my birth; my mother, Charlotte Macindi Louw, says it was in the early hours of the morning and that I was a plump baby.

She shared with me many memories of me as a little baby, some funny, some not. Once, she went to town to do some shopping with me, and some nosey women on the train made snide remarks about how the baby strapped on her back could not be hers. I had inherited the lighter skin of my fathers Barwa/Bushmen ancestors, and my mother was dark in comparison. These women even had the cheek to ask if I was indeed her child. Abanye abantu bayadelela, sometimes. My mother ignored them and when she got to Woolworths to buy my christening dress, the white staff were so taken by this beautiful baby that they took me in their arms and asked if they could take me to the manager, who gave me presents, including booties and matching woollen hats.

Another favourite is of my first experience eating solid food: a bit of mashed potatoes and minced meat. After a few spoons of mince, I apparently rolled over and fell asleep.

I grew up in the township of Orlando West 2, Mzimhlophe at 10415b Hadebe Street, Soweto, in a semi-detached four-room house with a small garden at the front, another at the back, and an outside toilet with no bathroom facilities. Four of us lived in the house: my parents, my sister and me.

My parents married in 1934 and my sister, Mabasotho Trueblue Louw, was born that same year. As was the norm back then, my father had to find work in the mines of Johannesburg so that he could provide for his family. My mother stayed behind to raise Mabasotho and look after my grandmother MaManini.

I never met my paternal grandfather, Samuel Louw. I am told he left my grandmother when my father was still a little boy. He never wanted to talk about his father, so it always seemed to me that there were issues lurking. Through conversations I was never supposed to be part of, I caught bits and pieces of what those issues were, and they included the physical and emotional abuse my grandmother suffered at the hands of my grandfather. As far as I know, my father was never in contact with his father after his departure from their lives. This is unfortunate; I would have loved to learn more about my familys connection to the Barwa.

My paternal grandparents had four children. My father, Mokgethi, born in January 1910, was the youngest. He had two sisters, Manini and Dimakatso, and a brother, Enock. Enock was forced to join the black South African soldiers during the Second World War. He survived, but shell shock prevented him from finding a job when he returned. He had these shaking episodes and could not even hold a spoon to feed himself.

My father and Dimakatso helped raise Enocks children, Botso and Sinet, who I came to think of as my brother and sister. By that time, Enock was herding cows and sheep up the mountains in the village. He never complained of being sick. One day he went up and never came back. The other herd boys told the family theyd seen him sleeping with his head resting on a rock but when they tried to wake him he was dead. I was too young to remember all the details.

My mother was born Charlotte Shalisha Macindi Nkolongwane in July 1911 to the Reverend Brigg Nkolongwane and Ellen Nkolongwane. She had eight siblings: Thandeka, Funiwe, Shalisha, Esther, Mthuthuzeli, Victor, Mlibazisi and Archiebald. They lived in Stone Hill village, not far from Boomplaas.

Although these were my parents immediate siblings, they were not their only brothers and sisters. Our families are large and complex, incorporating relatives and relationships that defy conventional definitions or simple explanations. Words like brother, sister, aunt, uncle or cousin have a familiarity that keeps us all close together, but they can encapsulate something very complicated or hide taboos that prevent you from being more specific. This is something that not only affects the way I think and talk about the people in my life, but which came to have far greater meaning than I could ever have realised.