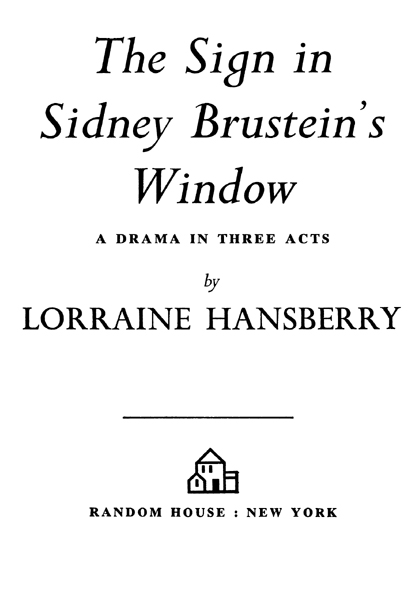

Copyright 1965, 1966 by Robert Nemiroff.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in somewhat different form by Random House, Inc., New York, in 1959 and 1965.

Caution: Professionals and amateurs are hereby warned that The Sign in Sidney Brusteins Window, being fully protected under the copyright Laws of the United States of America, the British Empire, including the Dominion of Canada, and all other countries of the Universal Copyright and Berne Conventions, are subject to royalty. All rights, including professional, amateur, motion picture, recitation, lecturing, public reading, radio and television broadcasting, and the rights of translation into foreign languages, are strictly reserved. Particular emphasis is laid on the question of readings, permission for which must be secured in writing. All inquiries should be addressed to the William Morris Agency, 1350 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY, 10019, authorized agents for the Estate of Lorraine Hansberry and for Robert Nemiroff, Executor.

www.vintagebooks.com

eISBN: 978-0-307-81553-8

v3.1

Contents

Foreword

In 1959 I dined with Kenneth Tynan at Sardis on a first night. There wasnt much doubt about the verdict of the reviewers, only about how nasty it would be. Theres no point in dancing on the corpse of that particular play; it was, and quite rightly, doomed from the start.

Nevertheless, I couldnt help feeling that what Walter Kerr and the rest had done had no connection whatever with criticism. To produce a coherent and literate review in one hour is an extraordinary feat; as a professional writer, I am honestly dazzled by it. But it is a feat which has about it the atmosphere of the circus sideshow. Its a job which could be performed even more quickly by a computer.

What I fiercely objected to that night at Sardis, waiting for the papers to arrive, was that the verdict was completely and savagely final. Since the play in question was a bad one, it didnt really matter; the kangaroo court wasnt hanging an innocent man. Sooner or later, however, a good playperhaps even a great playwould be condemned to death. Of its very nature the kangaroo court must be more often wrong than right.

With Lorraine Hansberrys The Sign in Sidney Brusteins Window it seemed to do just that, not with overt condemnation, but with the kind of mixed notices which spell death in a theatre where $6.90 buys the cheapest orchestra seat. The verdict was not reversed: there is no recorded instance of a drama critic having admitted himself to be mistaken. But the public can, as in this remarkable instance they did, storm the courtroom and set the prisoner free. The world was the richer for it. For a great play (I shall repeat thata great play) not only entertains but enriches, not only takes us out of ourselves but into ourselves as, nakedly, we are.

Let me be absolutely honest: I went to see Miss Hansberrys play partly because of A Raisin in the Sun and partly because it was the only new Broadway play I could easily obtain a ticket for. I paid for the ticket myself; I didnt know anyone connected with the production, and if the play hadnt held my interest I would have walked out; I wont accept boredom meekly.

There was a moment early on in the play when I became irritated because one wasnt told just where Sidney Brustein gets the money for his apartment in Greenwich Village and what does appear to be a pretty high standard of living. Then I realized that it didnt matter, because Sidney is a real person, as is everyone else in the play. Perhaps he writes Westerns under a pen name or has a private income; such things have been known to happen. Its a curious trait of drama critics that theyll accept the most fantastic variations of sexual behavior as credible but not be willing to accept that a man isnt always prepared to disclose the source of his income.

Apart from this there are no secrets in the play. No secrets but many levels. It is drama of such clarity that one may return to it again and again, and, I expect, emerge as deeply movedand each time the more illumined. And here, I imagine, we come to the true reason for the drama critics less than enthusiastic reception: the fact that there are no characters that can be dismissed or defined on the basis of personal relationships alone. Each is larger than expectation has permitted either them or us. There are no merely supporting actors, the equivalents of the spearman and the butler and the maid. All are real. All are involved in the lives of Sidney and Iris Brustein and they are all involved in their own lives. They arent there simply as sounding boards for Sidney, as sitting ducks for him to knock down, as causes for him to fight for. This isnt the sort of play with the hero (and sometimes the heroine) twopence-colored and the other characters penny-plain. Miss Hansberry, I am convinced, doesnt know how to create a character who isnt twopence-colored, who isnt gloriously diverse, illuminatingly contradictory, heart-breakingly alive.

From casual beginnings, lightly and humorously entered into, the play becomes Sidney Brusteins personal odyssey of discovery, a confrontation with others in the process of which he discovers himself.

His friend Alton, because his skin isnt white, has from his birth lived in a world of injustice; he is a victim, a martyr whether or not he wants to be one. This doesnt, however, prevent him when he discovers the truth about Gloria from being as prejudiced, as narrow, as unthinkingly cruel as the world which has persecuted him. To be a victim does not necessarily improve ones character, to live in a world without love is not the best way of learning how to love. Alton is intelligent and sensitive and warm-hearted, and yet he behaves as badly as a white man would do in the same position; and this is only one of the instances in which Miss Hansberry refuses to be influenced by progressive prejudiceswhich can be as blind and stupid as reactionary prejudices.

Indeed, she must have shocked a great many people whose pride is that they are unshockable. Mavis, one feels certain, knew in her heart that Goldwater was right, and is not only a segregationist but anti-Semite; but she is also intelligent and gentle and generous and brave and without hate, growing in one marvelous scene under Sidneys very eyes.

And David, the playwright, too is shocking. Its all very well for an audience to be asked to sympathize with a homosexuals sad predicament; its a different matter when we are shown that they are not only victims but make others their victims, that some do actually corrupt youth, and that above all, homosexuality is not a special order but a form of sex:

If somebody insults yousock em in the jaw. If you dont like the sex laws, attack them You wanna get up a petition? Ill sign one But, David, please get over the notion that your particular sexuality is something that only the deepest, saddest, the most nobly tortured can know about. It aintits just one kind of sexthats all. And, in my opinionthe universe turns regardless.